Unlikely Warrior (13 page)

Authors: Georg Rauch

I’m in tip-top shape again, rested up. My belly is full, and I’m also in quite a good mood. Today we’re having fried chicken and pudding with raspberry sauce as a farewell dinner. Tell Vienna hello for me. Thousand kisses,

Your Boy

Russia, February 11, 1944

Dear Mutti,

Oh dear, how my bones are aching. Yesterday we moved twenty-five kilometers closer to the front. Now we are situated five kilometers behind the main fighting line in a burned-out village. No chicken, no cow, just here and there a house still standing. This place is the springboard back into the trenches.

Oh yes, and I was on horseback those twenty-five kilometers, on five different nags! I feel like a seasoned rider now, one who knows all the tricks of the trade. The mud makes walking a torture. First you sink in up to your shins, and then you can’t get out again.

And so I, crafty old fox, organized a horse. Without saddle, naturally, just with a pair of narrow cords running somehow past the ears as reins. Of course, I don’t know the first thing about horses or riding, and it wasn’t until after the first three kilometers that I realized I was riding a pregnant mare who bucked and wouldn’t run.

Whereupon, without much ado, I went into a barn in the next village and took a different horse, and that one ran. That beast galloped, stood on its hind legs, and never went in the direction I wanted. But I stayed on him for about ten kilometers, until I spied another that I took to be quieter and more docile.

I changed horses once again and, what do you know, it walked quite peacefully behind the wagons, until an expert told me that it was a young horse, about two months old, and would collapse any moment. So I looked for the next horse and discovered shortly after mounting that it was limping. I finally arrived here with an old horse that had a runny nose, and after a few words of thanks, I took my leave of him with a slap on the rump.

Twice in the course of the day I was thrown, to the general amusement of all. I was rather amazed myself at the way I accomplished the separate stages of riding, from the slowest snail tempo to a full gallop.

All in all, it was a delightful experience: by the light of the moon, with a rifle on my back, just like an old cowboy riding over the endless fields. My thighs are pretty sore today though. When I have to walk, it’s with a sort of swagger. But I really slept well. In a few hours we are going up front to a bunker in the open fields. Then we’ll look like pigs again. But the front is quiet for the time being. I hope the mail gets through. I’ll write you again when circumstances permit. Till then, kisses and greetings to Pop,

Your Boy

On my twentieth birthday, I wrote the following:

Russia, February 14, 1944

Dear Mutti,

Please don’t be frightened when you see my writing. On a gear of a cable drum I ripped a hole about a centimeter deep in my right hand, just underneath the index finger. So I’m pretty clumsy, but otherwise I’m fine.

I was supposed to go up front with the company as radioman, but I couldn’t be transferred because of the injury. Maybe it is fate or my luck. The front continues very quiet here. Hardly a shot all day long. Those of us on the staff are headquartered in the last houses of the village. Here in Panchevo there is neither chicken nor cow. [Author’s note: Sometimes, against the regulations, I smuggled in the name of a town in the middle of a letter, in order to let my parents know where I was.] They were all eaten up by our predecessors. We are getting mail in masses now, every day a sack, but all old letters posted around Christmas or earlier. Writing is pretty difficult because the hole hurts quite a bit when I move my hand. Many loving greetings,

Your Son

Russia, February 18, 1944

Dear Mutti,

I’m not in the position of writing you such a positive letter today as the last ones have been. You mustn’t take what I write too tragically, since I’m considerably better off than most. Overnight it has become winter here again; that is, the true Russian winter. The temperature is running between ten and twenty-five below zero. You can barely move against the icy east storm. The ice needles tear your skin to pieces. You can see only three meters ahead.

Yesterday, in this weather, we marched for thirty kilometers. Left at 5 a.m. and reached our destination at about 11:30 p.m. Quite a few collapsed along the way and will be listed as missing. Probably somewhere in these unending fields they have frozen to death. One never knows. A few vehicles also disappeared. All that was left of us arrived here, more or less frozen.

“Here” is a

kolchos

. That is to say an enormous barn without windows or doors. Or rather, there are holes in the walls without wood or glass. Inside the snow is just as high as outside, and the wind howls, too. Way at the back are two rooms with a door, and these can be heated. Our battalion headquarters staff has holed up there.

The rest of the company just kept going forward to the trenches to relieve another unit. Then the night passed. I’m sitting here now in the morning at the switchboard, listening to the awful early reports: in every company some dead, many frozen, some suspected of self-inflicted wounds. Some just got out of the trenches and took off on their own.

Everyone else spent the whole night shoveling just to see the sky, since these two-man holes can fill up with snow in a matter of minutes. There’s been nothing to eat since yesterday morning, not even coffee. And so, the poor guys are lying out there day and night, slowly freezing to death. I also threw up four times last night, have diarrhea, and sat up all night on the wet ground near the drafty door. In spite of that, I feel like a plutocrat. Enough for today. Kisses from

Your Georg

February 19, 1944

Dear Folks,

A few hasty shivering words. The east wind howls through all the cracks. Your ninth package arrived today, with quince jam, tea, and cookies. Everything is so much easier when you’ve had a sign from home. Russia is so gruesome.

Continually, eighteen-year-olds with frozen hands are being sent to the rear. Practically nothing is left of us now. But I’m healthy and all right compared to the others.

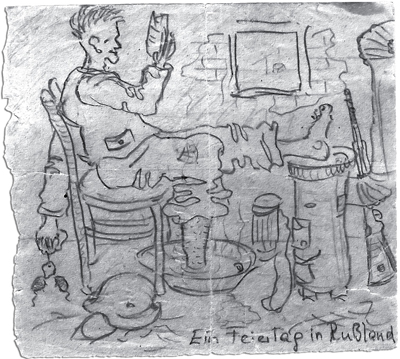

A holiday in Russia.

About June or July I can count on leave, if I’m not already back by then. Be well and don’t worry. Nothing will happen to me.

10,000 Bussis [Kisses], Your Son

February 21, 1944

Dear Mutti,

I’m still sitting here in my

kolchos

. We’ve been working day and night for the last few days, trying to get this place halfway stopped up. Now, if we heat all day, it gets nice and warm. We’ve also found some straw for sleeping. You can’t imagine how much that means, when outside the eternal east storm is blowing. At least one can warm a meal, toast some bread, and chase one’s hundred thousand lice.

A sign on our door reads, “Wireless Station, No Admittance,” but many half-frozen soldiers, passing by for one reason or another, beseech us to let them come in and warm up for a few minutes.

Once inside they sit around the little stove, quite silent and thoughtful, and revel in the great happiness of having warm hands and feet once again.

One thumbed through his notebook and suddenly said, “Did you know that today is Sunday?” Each one then described, almost as if speaking of something holy and long past, what he had done at this time of the week before the war. The others gazed silently into the fire. Perhaps some of them let visions of something beautiful from home pass in front of their eyes and were able thereby to forget for a few minutes their horrible current situation.

Sunday, for most soldiers, is the symbol of good times and relaxation. Maybe I think a little differently, since Sundays for us passed by almost just like all the other days. The big dates that many dream of, the bars, variety shows, and movies, weren’t so common for me. Maybe I had things so good that I never learned to appreciate the true value of Sundays? But it doesn’t matter.

When the soldiers leave after a half hour or forty-five minutes, they have new courage and the feeling of having experienced a few very special moments. Their eyes are glowing again, and thus they return back up front to the trenches.

It was your seventh package, not the ninth, that I received yesterday. Fantastic, and there’s hope of more mail. I sent you 159 marks today. Otherwise I’m doing fine, at least more or less. Many kisses,

Your Georg

P.S. The front is quiet.

Russia, February 26, 1944

Dear Mutti,

Quite late yesterday evening some mail arrived, including the letter you wrote on my birthday. I withdrew to a quiet corner and read. Afterward I noticed that my eyes were quite damp. Perhaps it was written with too much love for the disposition of a presently wild and degenerate fighter.

One becomes pretty hard in every respect here, and there are only a few things that really go all the way to the heart. A protecting wall absorbs most things before they get that far.

But when a mother writes from the distant homeland of her love for her son, and of the extremely favorable balance of the last twenty years, that goes all the way inside, even during the strongest bombardment. So, afterward one has wet eyes. It could happen to anyone.

Today the sun is shining beautifully; the snow is starting to thaw; the trenches are turning into mud holes again. The wind is blowing through the broken doors and windows. No wood, nothing to eat but “water soup,” one loaf of bread for four men, and unsalted sausage. So currently not very rosy, but I don’t think we will be here much longer. Kisses,

Your Son

March 2, 1944

Dear Papi,

Yesterday a few others from the staff and I went to a variety show in the village. The so-called Spotted Woodpeckers entertained us wonderfully for an hour and a half. It was a Viennese comedian, magician, and musical group from the army broadcasting station, Gustav, one that travels back and forth putting on shows for the soldiers.

It was very strange for me, here in the middle of cannons and uniforms, to see someone in civilian clothing on an improvised stage. They provided us with a wonderful change, and we certainly didn’t regret having trudged five kilometers in the morass to see it!

The Russians attack continuously to the north and south, but it is quiet where we are. In return for that, though, we are in serious danger of being hemmed in again. Very little is left to eat, and that little is no good. Give everyone my best greetings,

Your Georg

Other books

His Challenging Lover by Elizabeth Lennox

Work What You Got by Stephanie Perry Moore

Wicked Temptation (Nemesis Unlimited) by Zoë Archer

His Wicked Wish by Olivia Drake

Mother May I (Knight Games Book 4) by Genevieve Jack

Blind Dates Can Be Murder by Mindy Starns Clark

Fool's Gold by Glen Davies

The Companions of Tartiël by Jeff Wilcox

Love Not a Rebel by Heather Graham

Pies and Prejudice by Ellery Adams