Triumph and Tragedy (The Second World War) (21 page)

Read Triumph and Tragedy (The Second World War) Online

Authors: Winston S. Churchill

Triumph and Tragedy

129

7

Rome: The Greek Problem

Alexander Prepares to Attack the Gothic Line —

Field-Marshal Smuts Surveys the Situation,

August

12 —

IVisit the Front, August

17 —

Two

Days at Siena — The Weakening of the Fifteenth

Army Group — A Visit to General Mark Clark

—

Sombre Reflections — I Fly to Rome, August

21

— Preparations to Liberate Greece — My

Telegram to the President, August

17 —

His Reply

— A Meeting with M. Papandreou — The Future

of the Greek Monarchy — I Report to Mr. Eden,

August

22 —

IMeet Some Italian Politicians —

Audience with Pope Pius XII — The Crown Prince

Umberto, Lieutenant of the Realm.

D

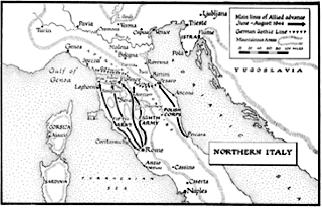

URINGTHE EARLY WEEKS of August Alexander was planning and regrouping his depleted forces to attack the main Gothic Line, with whose outpost positions he was already in close contact. Skilfully sited to make full use of the natural difficulties of the country, the main defences firmly barred all likely lines of approach from the south, leaving enticingly weak only those sectors which were almost inaccessible.

The difficulties of launching the attack directly through the mountains from Florence to Bologna were obvious, and Alexander decided that the Eighth Army should make the first major stroke on the Adriatic side, where the succession of river valleys, difficult though they would be, offered less

Triumph and Tragedy

130

unfavourable ground provided heavy rain held off.

Kesselring could not afford to have his eastern flank turned and Bologna captured behind his main front, so it was certain that if our attack made good progress he would have to reinforce the flank by troops from the centre.

Alexander therefore planned to have ready a second attack, to be carried out by Mark Clark’s Fifth Army, towards Bologna and Imola, which would be launched when enemy reserves had been committed and their centre weakened.

The preparatory troop and air movements, carried out in great secrecy during the third week of August, were skilfully accomplished. Leaving the XIIIth British Corps east of Florence to come under Fifth Army command, two whole corps of the Eighth Army were transferred eastward and concentrated near Pergola, on the left of the Polish Corps.

When all was completed Alexander held ready for battle the equivalent of twenty-three divisions, of which rather more than half were with the Eighth Army. Opposing him Kesselring had twenty-six German divisions, in good shape,

Triumph and Tragedy

131

and two reconstituted Italian divisions; nineteen of them were disposed for the defence of his main positions.

Smuts fully realised what was at stake, as the following telegram shows:

Field-Marshal Smuts

12 Aug. 44

to Prime Minister

Knowing how deeply occupied you are, I have

refrained from worrying you unduly with correspondence. I myself have also been fully engaged with

difficult local problems. I am glad to hear you are once

more in Italy, in close contact with that important

section of our war front, and wish you a very successful

and happy trip, as well as health and strength for the

exacting tasks still awaiting you.

2. I assumed that one of the objects of your present

visit will be to strengthen Alexander’s hands by

combing our Mediterranean theatre as drastically as

possible. Considerable forces must still be in reserve

there for contingencies now no longer important. The

end can best be hastened by the concentration of our

forces in the few decisive theatres, of which Alexander’s is one. With Turkey now lost to the enemy and

Bulgaria more and more shaky, we can afford to ignore

the theatres for which large forces have been kept in

the Middle East and assemble whatever we have to

strengthen Alexander’s move, which may lead to very

great results both in the Balkans and in Hitler’s

European fortress. I would cut off the frills elsewhere in

order to improve the alluring chances before this move.

A front extending along North Italy, the Adriatic, and the

route through Trieste to Vienna is one worthy of our

concentrated effort and of one of the ablest generals

this war has produced. I am sure both Wilson and

Paget agree that this is the correct strategy for us to

follow in order to complete our task and gather the

mature fruits of our great Mediterranean campaigns.

Triumph and Tragedy

132

Any further assistance I could still give from here is in

the air, and I have already offered to man a number of

additional squadrons from personnel released from the

air training schools now being closed down in the

Union. Already I am manning some R.A.F. squadrons

with South Africans, and by this means could probably

man six more for Alexander’s operations. As we are

now scraping the bottom in our recruiting campaign,

and owing to the dispersal of our man-power in many

other directions, I am unable to do more for the infantry

than keep up the strength of the 6th South African

Division. The additional air help would only be possible

if the Air Ministry accept my offer already made to them.

They have the details.

A decisive stage has now been reached in the war,

and an all-out offensive on all three main fronts against

Germany must lead to the grand finale this summer. If

the present tremendous successful offensive can only

be maintained the end cannot be long deferred,

especially in view of what we now know of conditions

inside the German Army.

I shall be glad to see the “Dragoon” correspondence, disheartening as it may be. The way things are

going now, Southern France has ceased to be a

theatre of real military significance, and our large forces

and resources detached for it will have small bearing on

the tremendous decisions elsewhere. I even doubt

whether the enemy will trouble to reinforce it.

On the morning of August 17 I set out by motor to meet General Alexander. I was delighted to see him for the first time since his victory and entry into Rome. He drove me all along the old Cassino front, showing me how the battle had gone and where the main struggles had occurred. The monastery towered up, a dominating ruin. Anyone could see the tactical significance of this stately crag and building which for so many weeks played its part in stopping our Triumph and Tragedy

133

advance. When we had finished it was time for lunch, and a picnic table had been prepared in an agreeable grove. Here I met General Clark and eight or ten of the leading British officers of the Fifteenth Army Group. Alexander then took me in his own plane, with which I was familiar, by a short flight to Siena, the beautiful and famous city, which I had visited in bygone peaceful days. Thence we visited our battle-front on the Arno. We had the south bank of the river and the Germans the north. Considerable efforts were made by both sides to destroy as little as possible, and the historic bridge at Florence was at any rate preserved. We were lodged in a beautiful but dismantled chateau a few miles to the west of Siena, and here I passed a couple of days, mostly working in bed, reading, and dictating telegrams. Of course in all these journeys I kept close to me the nucleus of my Private Office and the necessary ciphering staff, which enabled me to receive and to answer all messages from hour to hour.

Alexander brought his chief officers to dinner, and explained to me fully his difficulties and plans. The Fifteenth Group of Armies had indeed been skinned and starved. The far-reaching projects we had cherished must now be abandoned. It was still our duty to hold the Germans in the largest numbers on our front. If this purpose was to be achieved an offensive was imperative; but the well-integrated German armies were almost as strong as ours, composed of so many different contingents and races. It was proposed to attack along the whole front early on the 26th. Our right hand would be upon the Adriatic, and our immediate objective Rimini. To the westward, under Alexander’s command, lay the Fifth American Army. This had been stripped and mutilated for the sake of “Anvil,” but would nevertheless advance with vigour.

Triumph and Tragedy

134

On August 19 I set off to visit General Mark Clark at Leghorn. This was a long drive, and everywhere we stopped to visit brigades and divisions. Mark Clark received me at his headquarters. We lunched in the open air by the sea. In our friendly and confidential talks I realised how painful the tearing to pieces of this fine army had been to those who controlled it. I toured the harbour, which had often played a part in our naval affairs, in a motor torpedo-boat. Then we went to the American batteries. A pair of new 9-inch guns had just been mounted, and I was asked to fire the first shot. Everyone stood clear — I tugged a lanyard — there was a loud bang and a great recoil, and the observation post reported that the shell had hit its mark.

I claim no credit for the aim. Later I was asked to inspect and address a parade of the Brazilian Brigade, the forerunners of the Brazilian Division, which had just arrived and made an imposing spectacle, together with Negro and Japanese-American units.

All the time amid these diversions I talked with Mark Clark.

The General seemed embittered that his army had been robbed of what he thought — and I could not disagree —