Triumph and Tragedy (The Second World War) (20 page)

Read Triumph and Tragedy (The Second World War) Online

Authors: Winston S. Churchill

“Anvil,” and indeed I thought it was a good thing I was near the scene to show the interest I took in it. On the way back I found a lively novel,

Grand Hotel,

in the captain’s cabin, and this kept me in good temper till I got back to the Supreme Commander and the Naval Commander-in-Chief, who had passed an equally dull day sitting in the stern cabin.

On August 16 I got back to Naples, and rested there for the night before going up to meet Alexander at the front. I telegraphed to the King, from whom I had received a very kind telegram.

Prime Minister to the

17 Aug. 44

King

With humble duty.

From my distant view of the “Dragoon” operation,

the landing seemed to be effected with the utmost

smoothness. How much time will be taken in the

advance first to Marseilles and then up the Rhone

valley, and how these operations will relate themselves

to the far greater and possibly decisive operations in

the north [Normandy], are the questions that now arise.

2. I am proceeding today to General Alexander’s

headquarters. It is very important that we ensure that

Triumph and Tragedy

123

Alexander’s army is not so mauled and milked that it

cannot have a theme or plan of campaign. This will

certainly require a conference on something like the

“Quadrant” scale, and at the same place [Quebec].

3. My vigour has been greatly restored by the

change and movement and the warm weather. I hope

to see various people, including Mr. Papandreou, in

Rome, where I expect to be on the 21st. May I express

to Your Majesty the pleasure and encouragement

which Your Majesty’s gracious message gave me.

And to General Eisenhower:

Prime Minister to

18 Aug. 44

General Eisenhower

(France)

I am following with thrilled attention the magnificent

developments of operations in Normandy and Anjou. I

offer you again my sincere congratulations on the truly

marvellous results achieved, and hope for surpassing

victory. You have certainly among other things effected

a very important diversion from our attack at “Dragoon.”

I watched this landing yesterday from afar. All I have

learnt here makes me admire the perfect precision with

which the landing was arranged and the intimate

collaboration of British-American forces and organisations. I shall hope to come and see you and Montgomery before the end of the month. Much will have

happened by then. It seems to me that the results might

well eclipse all the Russian victories up to the present.

All good wishes to you and Bedell.

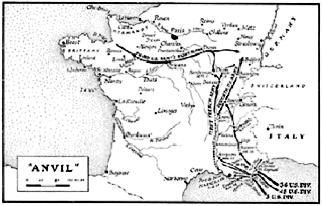

This chapter may close with an outline of the “Anvil-Dragoon” operations themselves.

The Seventh Army, under General Patch, had been formed to carry out the attack. It consisted of seven French and three U.S. divisions, together with a mixed American and British airborne division. The three American divisions comprised General Truscott’s VIth Corps, which had formed

Triumph and Tragedy

124

an important part of General Clark’s Fifth Army in Italy. In addition, up to four French divisions and a considerable part of the Allied air forces were withdrawn from Alexander’s command.

The new expedition was mounted from both Italy and North Africa, Naples, Taranto, Brindisi, and Oran being used as the chief loading-ports. Great preparations had been made throughout the year to convert Corsica into an advanced air base and to use Ajaccio as a staging-port for landing-craft proceeding to the assault from Italy. All these arrangements now bore fruit. Under the Commander-in-Chief, Admiral Sir John Cunningham, the naval attack was entrusted to Vice-Admiral Hewitt, U.S.N., who had had much experience in similar operations in the Mediterranean. Lieutenant-General Eaker, U.S.A.A.F., commanded the air forces, with Air Marshal Slessor as his deputy.

Landing-craft restricted the first seaborne landing to three divisions, and the more experienced Americans led the van.

Triumph and Tragedy

125

Shore defences all along the coast were strong, but the enemy were weak in numbers and some were of poor quality. In June there had been fourteen German divisions in Southern France, but four of these were drawn away to the fighting in Normandy, and no more than ten remained to guard the 200 miles of coastline. Only three of these lay near the beaches on which we landed. The enemy were also short of aircraft. Against our total of 5000 in the Mediterranean, of which 2000 were based in Corsica and Sardinia, they could muster a bare two hundred, and these were mauled in the days before the invasion. In the midst of the Germans in Southern France over 25,000 armed men of the Resistance were ready to revolt. We had sent them their weapons, and, as in so many other parts of France, they had been organised by some of that devoted band of men and women trained in Britain for the purpose during the past three years.

The strength of the enemy’s defences demanded a heavy preliminary bombardment, which was provided from the air for the previous fortnight all along the coast, and, jointly with the Allied Navies, on the landing beaches immediately before our descent. No fewer than six battleships, twenty-one cruisers, and a hundred destroyers took part. The three U.S. divisions, with American and French Commandos on their left, landed early on August 15 between Cannes and Hyères. Thanks to the bombardment, successful deception plans, continuous fighter cover, and good staff work, our casualties were relatively few. During the previous night the airborne division had dropped around Le Muy, and soon joined hands with the seaborne attack.

By noon on the 16th the three American divisions were ashore. One of them moved northward to Sisteron, and the other two struck northwest towards Avignon. The IInd French Corps landed immediately behind them and made

Triumph and Tragedy

126

for Toulon and Marseilles. Both places were strongly defended, and although the French were built up to a force of five divisions the ports were not fully occupied till the end of the month. The installations were severely damaged, but Port de Bouc had been captured intact with the aid of the Resistance, and supplies soon began to flow. This was a valuable contribution by the French forces under General de Lattre de Tassigny. In the meantime the Americans had been moving fast, and on August 28 were beyond Grenoble and Valence. The enemy made no serious attempt to stop the advance, except for a stiff fight at Montélimar by a Panzer division. The Allied Tactical Air Force was treating them roughly and destroying their transport. Eisenhower’s pursuit from Normandy was cutting in behind them, having reached the Seine at Fontainebleau on August 20, and five days later it was well past Troyes. No wonder the surviving elements of the German Nineteenth Army, amounting to a nominal five divisions, were in full retreat, leaving 50,000

prisoners in our hands. Lyons was taken on September 3, Besançon on the 8th, and Dijon was liberated by the Resistance Movement on the 11th. On that day “Dragoon”

and “Overlord” joined hands at Somber-non. In the triangle of Southwest France, trapped by these concentric thrusts, were the isolated remnants of the German First Army, over 20,000 strong, who freely gave themselves up.

To sum up the “Anvil-Dragoon” story, the original proposal at Teheran in November 1943, was for a descent on the south of France to help take the weight off “Overlord” [the landing in Normandy]. The timing was to be either in the week before or the week after D-Day. All this was changed by what happened in the interval. The latent threat from the Mediterranean sufficed in itself to keep ten German

Triumph and Tragedy

127

divisions on the Riviera. Anzio alone had meant that the equivalent of four enemy divisions was lost to other fronts.

When, with the help of Anzio, our whole battle line advanced, captured Rome and threatened the Gothic Line, the Germans hurried a further eight divisions to Italy. Delay in the capture of Rome and the despatch of landing-craft from the Mediterranean to help “Overlord” caused the postponement of “Anvil-Dragoon” till mid-August or two months later than had been proposed. It therefore did not in any way affect “Overlord.” When it was belatedly launched, it drew no enemy down from the Normandy battle theatre.

Therefore none of the reasons present in our minds at Teheran had any relation to what was done and “Dragoon”

caused no diversion from the forces opposing General Eisenhower. In fact instead of helping him, he helped it by threatening the rear of the Germans retiring up the Rhone Valley. This is not to deny that the operation as carried out eventually brought important assistance to General Eisenhower by the arrival of another army on his right flank, and the opening of another line of communications thither.

For this a heavy price was paid. The army of Italy was deprived of its opportunity to strike a most formidable blow at the Germans, and very possibly to reach Vienna before the Russians, with all that might have followed there-from.

But once the final decision was reached I of course gave

“Dragoon” my full support, though I had done my best to constrain or deflect it.

At this time I received some pregnant messages from Smuts, now back at the Cape. He had always agreed wholeheartedly with my views on “Dragoon,”“but,” he now wrote (August 30), “please do not let strategy absorb all Triumph and Tragedy

128

your attention to the damage of the greater issue now looming up.

“From now on it would be wise to keep a very close eye on

allmatters bearing on the future settlement of Europe. This

is the crucial issue on which the future of the world for

generations will depend. In its solution your vision,

experience, and great influence may prove a main factor.”

2

I have been taxed in the years since the war with pressing after Teheran, and particularly during these weeks under review, for a large-scale Allied invasion of the Balkans in defiance of American thinking on the grand strategy of the war.

The essence of my oft-repeated view is contained in the following reply to these messages from Smuts:

Prime Minister to

31 Aug. 44

Field-Marshal Smuts

Local success of “Dragoon” has quite delighted

Americans, who intend to use this route to thrust in

every reinforcement. Of course 45,000 prisoners have

been taken, and there will be many more. Their idea

now, from which nothing will turn them, is to work in a

whole Army Group through the captured ports instead

of using the much easier ports on the Atlantic.

“My object now,” I said, “is to keep what we have got in Italy, which should be sufficient since the enemy has withdrawn four of his best divisions. With this I hope to turn and break the Gothic Line, break into the Po valley, and ultimately advance by Trieste and the Ljubljana Gap to Vienna. Even if the war came to an end at an early date I have told Alexander to be ready for a dash with armoured cars.”