To Sell Is Human: The Surprising Truth About Moving Others (9 page)

Read To Sell Is Human: The Surprising Truth About Moving Others Online

Authors: Daniel H. Pink

Tags: #Psychology, #Business

Remapped conditions require revamped navigation. So here in Part Two, I introduce the new ABCs of moving others:

A—Attunement

B—Buoyancy

C—Clarity

Attunement, buoyancy, and clarity: These three qualities, which emerge from a rich trove of social science research, are the new requirements for effectively moving people on the remade landscape of the twenty-first century. We begin in this chapter with A—Attunement. And to help you understand this quality, let me get you thinking about another letter.

Power, Empathy, and Chameleons

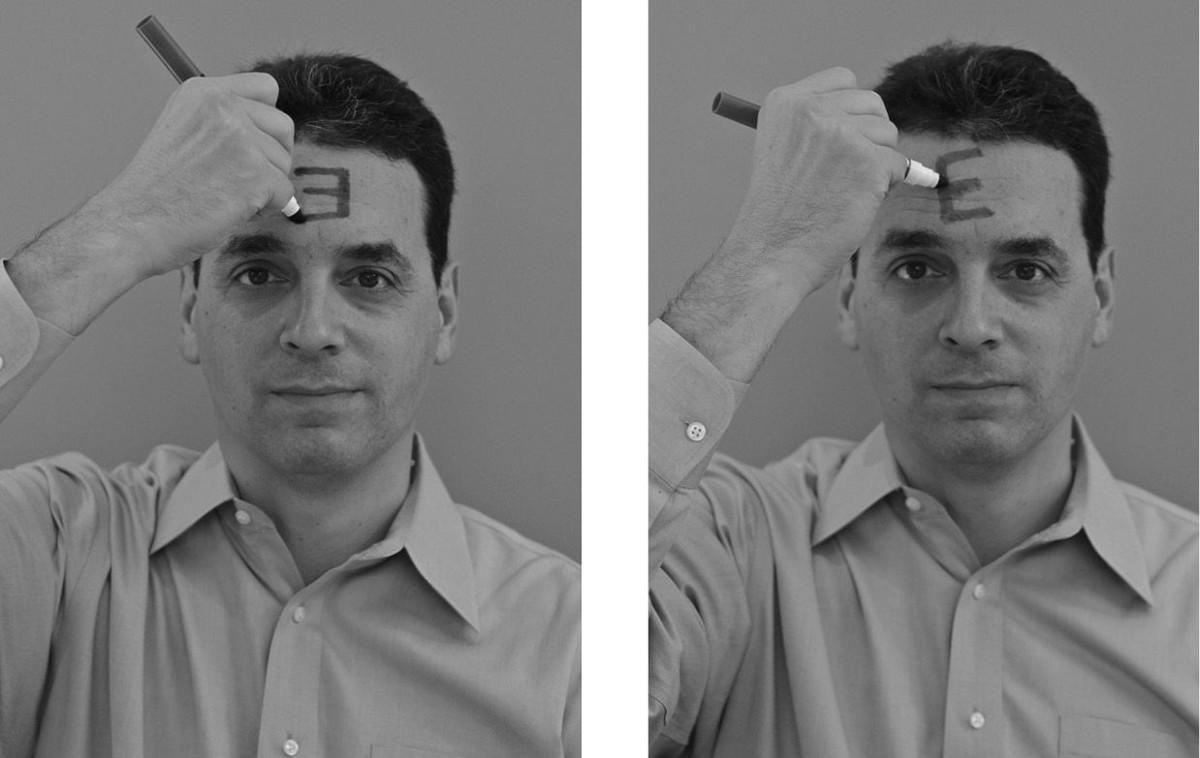

Take a moment right now—and if there’s someone in the room with you, politely request thirty seconds of his or her time. Then ask that person to do the following: “First, with your dominant hand, snap your fingers five times as quickly as you can. Then, again as quickly as you can, use the forefinger of your dominant hand to draw a capital E on your forehead.” Seriously, go ahead and do this. I’ll wait. (If you’re alone, slip this exercise in your back pocket and pull it out at your next opportunity.)

Now look at the way your counterpart drew his or her E. Which photograph above does it look like?

The difference might seem innocuous, but the letter on your counterpart’s forehead offers a window into his mind. If the E resembles the one on the left, the person drew it so he could read it himself. If it looks likes the one on the right, he drew the E so

you

could read it.

Since the mid-1980s, social psychologists have used this technique—call it the E Test—to measure what they dub “perspective-taking.” When confronted with an unusual or complex situation involving other people, how do we make sense of what’s going on? Do we examine it from only our own point of view? Or do we have “the capability to step outside [our] own experience and imagine the emotions, perceptions, and motivations of another?”

1

Perspective-taking is at the heart of our first essential quality in moving others today. Attunement is the ability to bring one’s actions and outlook into harmony with other people and with the context you’re in. Think of it as operating the dial on a radio. It’s the capacity to move up and down the band as circumstances demand, locking in on what’s being transmitted, even if those signals aren’t immediately clear or obvious.

The research shows that effective perspective-taking, attuning yourself with others, hinges on three principles.

1. Increase your power by reducing it.

In a fascinating study a few years ago, a team of social scientists led by Adam Galinsky at Northwestern University’s Kellogg School of Management probed the relationship between perspective-taking and power. They divided their participants into two groups, the only difference being what each experienced immediately before the key experiment. One group completed a series of exercises that induced feelings of power. The other did a different set of activities designed to emphasize their lack of power.

Then researchers gave the people in each group the E Test. The results were unmistakable: “High-power participants were almost three times as likely as low-power participants to draw a self-oriented ‘E.’”

2

In other words, those who’d received even a small injection of power became less likely (and perhaps less able) to attune themselves to someone else’s point of view.

Now try another test on yourself, one that doesn’t require anybody’s forehead. Imagine that you and your colleague Maria go out to a fancy restaurant that’s been recommended by Maria’s friend Ken. The experience is awful. The food stinks, the service is worse. The following day Maria sends Ken an e-mail that says only, “About the restaurant, it was marvelous, just marvelous.” How do you think Ken will interpret the comment? Will he consider the e-mail sincere or sarcastic? Think about it for a moment before reading further.

In a related experiment, Galinsky and his crew used a version of this scenario to examine power and perspective-taking from another angle—and found results similar to what they uncovered with the E Test. Participants with high power generally believed that Ken found the e-mail sarcastic; those with low power predicted he found it sincere. Who’s correct? Chances are, it’s the low-power group. Remember: Ken has no idea what happened at the dinner. Unless Maria is a chronically sarcastic person, of which there was no evidence in the experiment, Ken has no reason to suspect insincerity on the part of his friend. To conclude that he inferred sarcasm in Maria’s e-mail depends on “privileged background knowledge” that Ken doesn’t have. As the researchers conclude, “power leads individuals to anchor too heavily on their own vantage point, insufficiently adjusting to others’ perspective.”

3

The results of these studies, part of a larger body of research, point to a single conclusion: an inverse relationship between power and perspective-taking. Power can move you off the proper position on the dial and scramble the signals you receive, distorting clear messages and obscuring more subtle ones.

This is a hugely important insight for understanding how to move others. The ability to take another’s perspective mattered less when sellers—whether a commissioned salesperson in an electronics store or a physician in her diploma-studded office—held all the cards. Their edge in information—again, whether that information was the reliability of a clock radio or the experiences of patients with Lyme disease—gave them the ability to command through authority and sometimes even to coerce and manipulate. But as that information advantage has withered, so has the power it once conferred. As a result, the ability to move people now depends on power’s inverse: understanding another person’s perspective, getting inside his head, and seeing the world through his eyes. And doing that well requires beginning from a position that would get you expelled from the Mitch and Murray always-be-closing school of sales: Assume that you’re

not

the one with power.

Research by Dacher Keltner at the University of California, Berkeley, and others has shown that those with lower status are keener perspective-takers. When you have fewer resources, Keltner explained in an interview, “you’re going to be more attuned to the context around you.”

4

Think of this first principle of attunement as persuasion jujitsu: using an apparent weakness as an actual strength. Start your encounters with the assumption that you’re in a position of lower power. That will help you see the other side’s perspective more accurately, which, in turn, will help you move them.

Don’t get the wrong idea, though. The capacity to move others doesn’t call for becoming a pushover or exhibiting saintly levels of selflessness. Attunement is more complicated than that, as the second principle is about to demonstrate.

2. Use your head as much as your heart.

Social scientists often view perspective-taking and empathy as fraternal twins—closely related, but not identical. Perspective-taking is a cognitive capacity; it’s mostly about thinking. Empathy is an emotional response; it’s mostly about feeling. Both are crucial. But Galinsky, William Maddux at INSEAD business school in Fontainebleau, France, and two additional colleagues have found that one is more effective when it comes to moving others.

In a 2008 experiment, the researchers simulated a negotiation over the sale of a gas station. Like many real-life negotiations, this one presented what looked like an obstacle: The highest price the buyer would pay was less than the lowest price the seller would accept. However, the parties had other mutual interests that, if surfaced, could lead to a deal both would accept. One-third of the negotiators were instructed to imagine what the other side was

feeling

, while one-third was instructed to imagine what the other side was

thinking

. (The remaining third, given bland and generic instructions, was the control group.) What happened? The empathizers struck many more deals than the control group. But the perspective-takers did even better: 76 percent of them managed to fashion a deal that satisfied both sides.

Something similar happened in another negotiation situation, this one involving a set of thornier and more conflicting issues between a recruiter and a job candidate. Once again, the perspective-takers fared best, not only for themselves but also for their negotiation partners. “Taking the perspective of one’s opponent produced both greater joint gains and more profitable individual outcomes. . . . Perspective takers achieved the highest level of economic efficiency, without sacrificing their own material gains,” Galinsky and Maddux wrote. Empathy, meanwhile, was effective but less so “and was, at times, a detriment to both discovering creative solutions and self-interest.”

5

Traditional sales and non-sales selling often involve what look like competing imperatives—cooperation versus competition, group gain versus individual advantage. Pushing too hard is counterproductive, especially in a world of

caveat venditor

. But feeling too deeply isn’t necessarily the answer either—because you might submerge your own interests. Perspective-taking seems to enable the proper calibration between the two poles, allowing us to adjust and attune ourselves in ways that leave both sides better off. Empathy can help build enduring relationships and defuse conflicts. In medical settings, according to one prominent physician, it is “associated with fewer medical errors, better patient outcomes, more satisfied patients . . . fewer malpractice claims and happier doctors.”

6

And empathy is valuable and virtuous in its own right. But when it comes to moving others, perspective-taking is the more effective of these fraternal twins. As the researchers say, ultimately it’s “more beneficial to get inside their heads than to have them inside one’s own heart.”

7

This second principle of attunement also means recognizing that individuals don’t exist as atomistic units, disconnected from groups, situations, and contexts. And that requires training one’s perspective-taking powers not only on people themselves but also on their relationships and connections to others. An entire field of study, social network analysis, has arisen in the last fifteen years to reveal these connections, relationships, and information flows.

8

In most sales situations, however, we don’t have the luxury of the deep research and fancy software that social network analysts use. So we must rely less on GPS-style directions—and more on our intuitive sense of where we are. In the world of waiters and waitresses, this sort of attunement is called “having eyes” or “reading a table.” It allows the server to quickly interpret the group dynamics and adjust his style accordingly. In the world of moving others, I call this ability “social cartography.” It’s the capacity to size up a situation and, in one’s mind, draw a map of how people are related.

“I do this in every sales situation,” says Dan Shimmerman, founder of Varicent Software, a blazingly successful Toronto company recently acquired by IBM. “For me it’s very important to not just have a good understanding of the key players involved in making a decision, but to understand what each of their biases and preferences are. The mental map gives a complete picture, and allows you to properly allocate time, energy and effort to the right relationships.” Social cartography—drawing that map in your head—ensures that you don’t miss a critical player in the process, Shimmerman says. “It would stink to spend a year trying to sell Mary only to learn that Dave was the decision maker.”

Nonetheless, attunement isn’t a merely cognitive exercise. It also has a physical component, as our third principle of attunement will show.

3. Mimic strategically.

Human beings are natural mimickers. Without realizing it, we often do what others do—mirroring back their “accents and speech patterns, facial expressions, overt behaviors, and affective responses.”

9

The person we’re talking to crosses her arms; we do the same. Our colleague takes a sip of water; so do we. When we notice such imitation, we often take a dim view of it. “Monkey see, monkey do,” we sniff. We smirk about those who “ape” others’ behavior or “parrot” back their words as if such actions somehow lie beneath human dignity. But scientists view mimicry differently. To them, this tendency is deeply human, a natural act that serves as a social glue and a sign of trust. Yet they, too, assign it a nonhuman label. They call it the “chameleon effect.”

10

In an award-winning study, Galinsky and Maddux, along with Stanford University’s Elizabeth Mullen, tested whether mimicry deepened attunement and enhanced the ability to move others. They used the same scenarios as in the previous study—the gas station sale and the negotiation between a job hunter and a recruiter—but added a new dimension. Five minutes before the exercise began, some of the participants received an “important message” that gave them additional instructions for carrying out their assignment: