To Sell Is Human: The Surprising Truth About Moving Others (23 page)

Read To Sell Is Human: The Surprising Truth About Moving Others Online

Authors: Daniel H. Pink

Tags: #Psychology, #Business

Lainie Heneghan, a British consultant who advocates what she calls “radical listening,” offers some ways to test whether you’ve slowed down enough. Are your conversation partners actually finishing their sentences? Are people getting their perspective fully on the table without your interrupting? Do they have time to take a breath before you start yapping? Taking it slower can take you further.

Say “Yes and.”

One classic improv exercise is “The Ad Game.” Here’s how it works.

Select four or five participants. Then ask them to invent a new product and devise an advertising campaign for it. As players contribute testimonials or demonstrations or slogans, they must begin each sentence with “Yes and,” which forces them to build on the previous idea. You can’t refute what your colleagues say. You can’t ignore it. And you shouldn’t plan ahead. Just say “Yes and,” accept what the person before you offers, and use it to construct an even better campaign.

“There are people who prefer to say ‘Yes,’ and there are people who prefer to say ‘No,’” Keith Johnstone writes. “Those who say ‘Yes’ are rewarded by the adventures they have. Those who say ‘No’ are rewarded by the safety they attain.”

Play “Word-at-a-time.”

This is another classic improv game that has spawned lots of variations, though I like Johnstone’s version best. The rules are simple. Six to eight people sit in a circle and collectively craft a story. The hitch: Each person can add only one word and only when it’s his turn.

In

Improv for Storytellers

, Johnstone describes one session with two partners helping him create. He began with the word “Sally” and what followed was this:

— Was . . .

— Going . . .

(It’s my turn again, and I stir things up:) Mad . . .

— Because . . .

— Her . . .

— Father . . .

— Wanted . . .

— To . . .

— Put . . .

— His . . .

— Horse . . .

— Into . . .

— Her . . .

— Stable.

Johnstone says, “Some of these stories fizzle out after one sentence, but some may complete themselves.” However the tales unfold, this exercise is great for helping you to think quickly and to tune your ears to offers.

Enlist the power of questions.

One of the Salit session exercises I enjoyed the most, “I’m Curious,” is worth replicating on your own. Find a partner. Then choose a controversial issue that has two distinct and opposed sides. Before you begin, have your partner decide her position on the issue. Then you take the opposite stance. She then makes her case, but you can reply only with questions—not with statements, counterarguments, or insults.

These questions must also abide by three rules: (1) You cannot ask yes-no questions. (2) Your questions cannot be veiled opinions. (3) Your partner must answer each question.

This is tougher than it sounds. But with practice, you’ll learn to use the interrogative to elevate and engage both your partner and yourself.

Read these books.

Impro: Improvisation and the Theatre

by Keith Johnstone. If improvisational theater has a Lenin—a well-spoken revolutionary who provides a movement its intellectual underpinnings—that person is Johnstone. His book isn’t always easy reading. It’s as much a philosophical tract as the guidebook it purports to be. But it’s an excellent primer for grasping the underlying principles of improvisation.

Improvisation for the Theater

by Viola Spolin. If improvisational theater has an Eve—someone who was present at the creation, though in this case didn’t need an Adam and didn’t fall to temptation—it’s Viola Spolin. This book, which came out fifty years ago, but whose updated edition remains a brisk seller, collects more than two hundred of Spolin’s improv exercises.

Creating Conversations: Improvisation in Everyday Discourse

by R. Keith Sawyer. Sawyer is a leading scholar of creativity. In this 2001 book, he zeroes in on our everyday conversations and shows how much these quotidian exchanges have in common with jazz, children’s play, and improvisational theater. Also worth looking at is Sawyer’s

Group Genius: The Creative Power of Collaboration

.

Improv Wisdom: Don’t Prepare, Just Show Up

by Patricia Ryan Madson.

Madson, who taught drama at Stanford University until 2005, serves up thirteen maxims drawn from improv that readers can apply to their work and life.

The Second City Almanac of Improvisation

by Anne Libera. One part entertainment history, another part improv guidebook, this almanac charts the rise of the Second City improv juggernaut. It’s sprinkled with interesting exercises, provocative quotations on the craft, and lots of photos of well-known comedians when they were very young.

Use your thumbs.

This is a group activity that you can use to make a memorable point. Along with yourself, you’ll need at least two more people as participants.

Have everyone assemble themselves into pairs. Then ask each pair to “hook the fingers of your right hands and raise your thumbs.” Then, give the sole instruction: “Now get your partner’s thumb down.” Remain silent and allow the pairs to finish the task.

Most participants will assume that your instructions mean for them to thumb-wrestle. However, there are many other ways that they could get their partner’s thumb down. They could ask nicely. They could unhook their own fingers and put their own thumb down. And so on.

The lesson here is that too often our starting point is competition—a win-lose, zero-sum approach rather than the win-win, positive-sum approach of improvisation. In most circumstances that involve moving others, we have several ways to accomplish a task, most of which can make our partners look good in the process.

9.

Serve

I

f you want to travel from one town to another in Kenya, you’ll probably have to step into a

matatu

, a small bus or fourteen-seat minivan that constitutes the country’s main form of long-distance transportation. And if you do board one, prepare to be terrified. A young male behind the wheel of a fast-moving vehicle can be perilous in any country, but Kenyans say

matatu

drivers are especially unhinged. Like something out of

The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde

, otherwise kind and even-tempered Kenyan men become wild-eyed, speed-limit-crushing demons who put their passengers’ lives, and their own, in danger. Partly as a consequence, Kenya has one of the highest per capita rates of traffic deaths in the world.

1

In developing countries, road accidents now kill the same number of people as does malaria. Across the globe nearly 1.3 million people die in traffic accidents each year, making traffic injuries the world’s ninth leading cause of death. The World Health Organization projects that by 2030, they will be the fifth-largest killer, ahead of HIV/AIDS, diabetes, and war and violence.

2

Countries like Kenya call on a number of remedies for this problem. They can decrease speed limits, repair hazardous and damaged roads, encourage seat belt use, install speed bumps, and crack down on drunk driving. Many of these measures can reduce the grisly toll, but all require public money or vigilant enforcement, both of which are in short supply.

So in an ingenious field study, two Georgetown University economists, James Habyarimana and William Jack, devised a method to change the behavior of Kenya’s daredevil drivers.

3

Working with the cooperatives that own the vehicles, Habyarimana and Jack recruited 2,276

matatu

drivers

.

They divided everyone into two groups. Drivers with vehicles whose license plates ended in an even number became the control group. Those with an odd final digit on their license plates took part in a unique intervention. Inside each of these

matatu

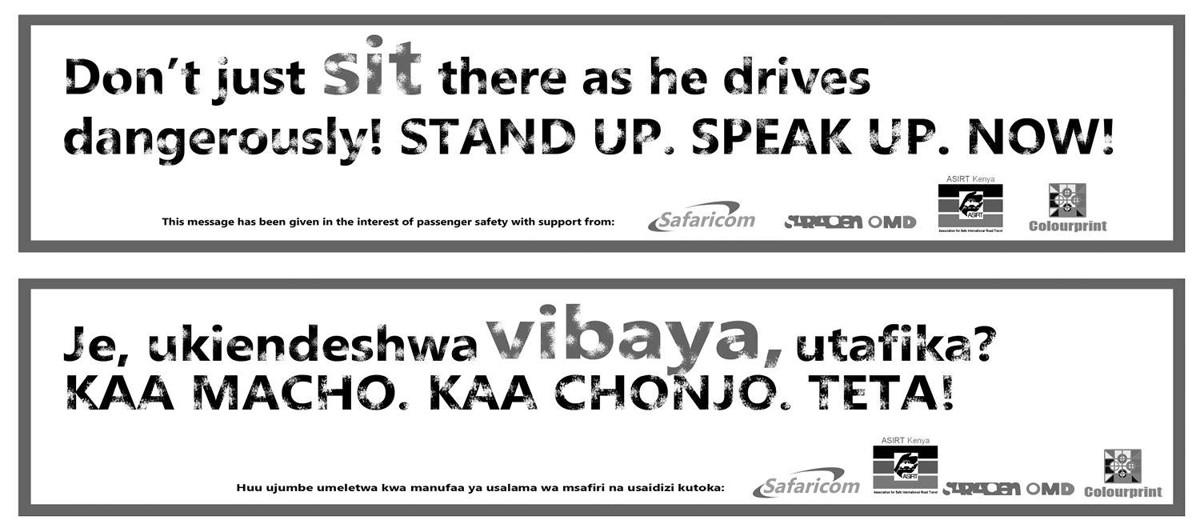

s, researchers placed five stickers, in both English and Kiswahili (Kenya’s national language). Some of the stickers included only words, like the ones below.

*

Others featured text accompanied by “explicit and gruesome images of severed body parts.”

4

But all urged passengers to take action—to implore their driver to slow down, to complain loudly when he attempted breakneck maneuvers, and to browbeat him until he operated the

matatu

more like mild-mannered Dr. Jekyll than maniacal Mr. Hyde. The researchers dubbed their strategy “heckle and chide.”

Over the next year, the team found that passengers riding in

matatu

s bearing stickers were three times as likely to heckle drivers as those in the stickerless

matatu

s. But did the efforts of these loudmouthed passengers move the drivers or affect the safety of their journeys?

To find out, the researchers examined a database of claims from the insurance companies that covered the

matatu

s. The results: Total insurance claims for the vehicles with stickers fell by nearly two-thirds from the year before. Claims for serious accidents (those involving injury or death) fell by more than 50 percent. And based on follow-up interviews the researchers conducted with drivers, it was clear that the passengers’ vocal persuasion efforts were the reason.

5

In other words, adding a few stickers to the minibuses saved more money and spared more lives than just about any other effort the Kenyan government had tried. And the mechanism at work here—the stickers moved the passengers and the passengers moved the driver—offers a useful way to understand our third and final skill: to serve.

Sales and non-sales selling are ultimately about service. But “service” isn’t just smiling at customers when they enter your boutique or delivering a pizza in thirty minutes or less, though both are important in the commercial realm. Instead, it’s a broader, deeper, and more transcendent definition of service—improving others’ lives and, in turn, improving the world. At its best, moving people can achieve something greater and more enduring than merely an exchange of resources. And that’s more likely to happen if we follow the two underlying lessons of the

matatu

sticker triumph: Make it personal and make it purposeful.

Make it personal.

Radiologists lead lonely professional lives. Unlike many physicians, who spend large parts of their days interacting directly with patients, radiologists often sit alone in dimly lit rooms or hunched over computers reading X-rays, CT scans, and MRIs. Such isolation can dull these highly skilled doctors’ interest in their jobs. And worse, if the work begins to feel impersonal and mechanical, it can diminish their actual performance.

A few years ago, a young Israeli radiologist named Yehonatan Turner had an inkling about how to move his fellow practitioners to do their jobs with more gusto and greater skill. Working as a resident at Shaare Zedek Medical Center in Jerusalem, Turner arranged, with patients’ consent, to take photos of about three hundred people coming in for a computed tomography (CT) scan. Then he enlisted a group of radiologists, who didn’t know what he was studying, for an experiment.

When the radiologists sat at their computers and called up one of these patients’ CT scans to make an assessment, the patient’s photograph automatically appeared next to the image. After they’d made their assessments, the radiologists completed a questionnaire. All of them reported feeling “more empathy to the patients after seeing the photograph” and being more meticulous in the way they examined the scan.

6

But the real power of Turner’s idea revealed itself three months later.

One of the skills that separate outstanding radiologists from average ones is their ability to identify what are called “incidental findings,” abnormalities on a scan that the physician wasn’t looking for and that aren’t related to the ailment for which the patient is being treated. For example, suppose I suspect that I’ve broken my arm and I go to the hospital for an X-ray. The doctor’s main job is to see if my ulna is fractured. But if she also spots an unrelated cyst near my elbow, that’s an “incidental finding.” Turner selected eighty-one of the photo-accompanied scans in which his radiologists had found incidental findings and presented them again to the same group of radiologists three months later—only this time

without

the picture of the patient. (Because radiologists read so many images each day, and because they were blind to what Turner was studying, they didn’t know they’d already seen these particular scans.)