To Sell Is Human: The Surprising Truth About Moving Others (11 page)

Read To Sell Is Human: The Surprising Truth About Moving Others Online

Authors: Daniel H. Pink

Tags: #Psychology, #Business

The answer, though, isn’t to lurch to the opposite side of the spectrum. Introverts have their own, often reverse, challenges. They can be too shy to initiate and too timid to close. The best approach is for the people on the ends to emulate those in the center. As some have noted, introverts are “geared to inspect,” while extraverts are “geared to respond.”

35

Selling of any sort—whether traditional sales or non-sales selling—requires a delicate balance of inspecting and responding. Ambiverts can find that balance. They know when to speak up and when to shut up. Their wider repertoires allow them to achieve harmony with a broader range of people and a more varied set of circumstances. Ambiverts are the best movers because they’re the most skilled attuners.

For most of you, this should be welcome news. Look again at the shape of the curve in that second chart. That’s pretty much what the distribution of introverts and extraverts looks like in the wider population.

36

A few of us are extraverts. A few of us are introverts. But most of us are ambiverts, sitting near the middle, not the edges, happily attuned to those around us. In some sense, we are born to sell.

SAMPLE CASE

Attunement

Discover the best way to start a conversation.

Everything good in life—a cool business, a great romance, a powerful social movement—begins with a conversation. Talking with each other, one to one, is human beings’ most powerful form of attunement. Conversations help us understand and connect with others in ways no other species can.

But what’s the best way to start a conversation—especially with someone you don’t know well? How can you quickly put the person at ease, invite an interaction, and build rapport?

For guidance, look to Jim Collins, author of the classic

Good to Great

and other groundbreaking business books. He says his favorite opening question is:

Where are you from?

The wording allows the other person to respond in a myriad of ways. She might talk in the past tense about location (“I grew up in Berlin”), speak in present tense about her organization (“I’m from Chiba Kogyo Bank”), or approach the question from some other angle (“I live in Los Angeles, but I’m hoping to move”).

This question has altered my own behavior. Because I enjoy hearing about people’s experiences at work, I often ask people:

What do you do?

But I’ve found that a few folks squirm at this because they don’t like their jobs or they believe that others might pass judgment. Collins’s question is friendlier and more attuned. It opens things up rather than shuts them down. And it always triggers an interesting conversation about something.

Practice strategic mimicry.

Gwen Martin says that what makes some salespeople extraordinary is their “ability to chameleon”—to adjust what they do and how they do it to others in their midst. So how can you teach yourself to be a bit more like that benevolent lizard and begin to master the techniques of strategic mimicry?

The three key steps are

Watch

,

Wait

, and

Wane

:

- Watch.

Observe what the other person is doing. How is he sitting? Are his legs crossed? His arms? Does he lean back? Tilt to one side? Tap his toe? Twirl his pen? How does he speak? Fast? Slow? Does he favor particular expressions? - Wait.

Once you’ve observed, don’t spring immediately into action. Let the situation breathe. If he leans back, count to fifteen, then consider leaning back, too. If he makes an important point, repeat back the main idea verbatim—but a bit later in the conversation. Don’t do this too many times, though. It’s not a contest in which you’re piling up points per mimic. - Wane.

After you’ve mimicked a little, try to be less conscious of what you’re doing. Remember: This is something that humans (including you) do naturally, so at some point, it will begin to feel effortless. It’s like driving a car. When you first learn, you have to be conscious and deliberate. But once you’ve acquired some experience, you can proceed by instinct.

Again, the objective here isn’t to be false. It’s to be strategic—by being human. “Subtle mimicry comes across as a form of flattery, the physical dance of charm itself,”

The New York Times

has noted. “And if that kind of flattery doesn’t close a deal, it may just be that the customer isn’t buying.”

Pull up a chair.

Jeff Bezos, the founder of Amazon.com, has accomplished a great deal in his forty-eight years. He’s reshaped the retail business. He’s become one of the thirty wealthiest people on the planet. And with far less fanfare, he’s devised one of the best attunement practices I’ve encountered.

Amazon, like most organizations, has lots of meetings. But at the important ones, alongside the chairs in which his executives, marketing mavens, and software jockeys take their places, Bezos includes one more chair that remains empty. It’s there to remind those assembled who’s really the most important person in the room: the customer.

The empty chair has become legendary in Amazon’s Seattle headquarters. Seeing it encourages meeting attendees to take the perspective of that invisible but essential person. What’s going through her mind? What are her desires and concerns? What would she think of the ideas we’re putting forward?

Try this in your own world. If you’re crafting a presentation, the empty chair can represent the audience and its interests. If you’re gathering material for a sales call, it can help generate possible objections and questions the other party might raise. If you’re preparing a lesson plan, an empty chair can remind you to see things from your students’ perspective.

Attuning yourself to others—exiting your own perspective and entering theirs—is essential to moving others. One smart, easy, and effective way to get inside people’s heads is to climb into their chairs.

Get in touch with your inner ambivert.

Wharton’s Adam Grant has discovered that the most effective salespeople are ambiverts, those who fall somewhere in the middle of the introversion-extraversion scale.

Are you one of them?

Take a moment to find out. Visit this link—http://www .danpink.com/assessment—where I’ve replicated the assessment that social scientists use to measure introversion and extraversion. It will take about five minutes to complete and you’ll get a rating when you’re done.

If you find you’re an ambivert, congrats on being average! Continue what you’re doing.

If you test as an extravert, try practicing some of the skills of an introvert. For example, make fewer declarations and ask more questions. When you feel the urge to assert, hold back instead. Most of all, talk less and listen more.

If you turn out to be an introvert, work on some of the skills of an extravert. Practice your “ask” in advance, so you don’t flinch from it when the moment arrives. Goofy as it might sound, make a conscious effort to smile and sit up straight. Even if it’s uncomfortable, speak up and state your point of view.

Most of us aren’t on the extremes—uniformly extraverted or rigidly introverted. We’re in the middle—and that allows us to move up and down the curve, attuning ourselves as circumstances demand, and discovering the hidden powers of ambiversion.

Have a conversation with a time traveler.

Cathy Salit, whom you’ll meet in Chapter 8, has an exercise to build the improvisational muscles of her actors that can also work to hone anyone’s powers of attunement. She calls it “Conversation with a Time Traveler.” It doesn’t require any props or equipment, just a little imagination and a lot of work.

Here’s how it goes:

Gather a few people and ask them to think of items that somebody from three hundred years ago would not recognize. A traffic light, maybe. A carry-out pizza. An airport screening machine. Then divide into groups of two. Each pair selects an item. One person plays the role of someone from the early 1700s. The other has to explain the item.

This is more difficult than it sounds. That person from three hundred years ago has a perspective wildly different from our own. For instance, to explain, say, a Big Mac bought from a drive-through window requires understanding a variety of underlying concepts: owning an automobile, consuming what three hundred years ago was a preposterous amount of meat, trusting someone you’ve likely never met and will never see again, and so on.

“This exercise immediately challenges your assumptions about the understandability of your message,” Salit says. “You are forced to care about the worldview of the other person.” That’s something we all should be doing a lot more of in the present.

Map it.

Walking a mile in another’s shoes sometimes requires a map. Here are two new varieties that can provide a picture of where people are coming from and where they might be going.

1. Discussion Map

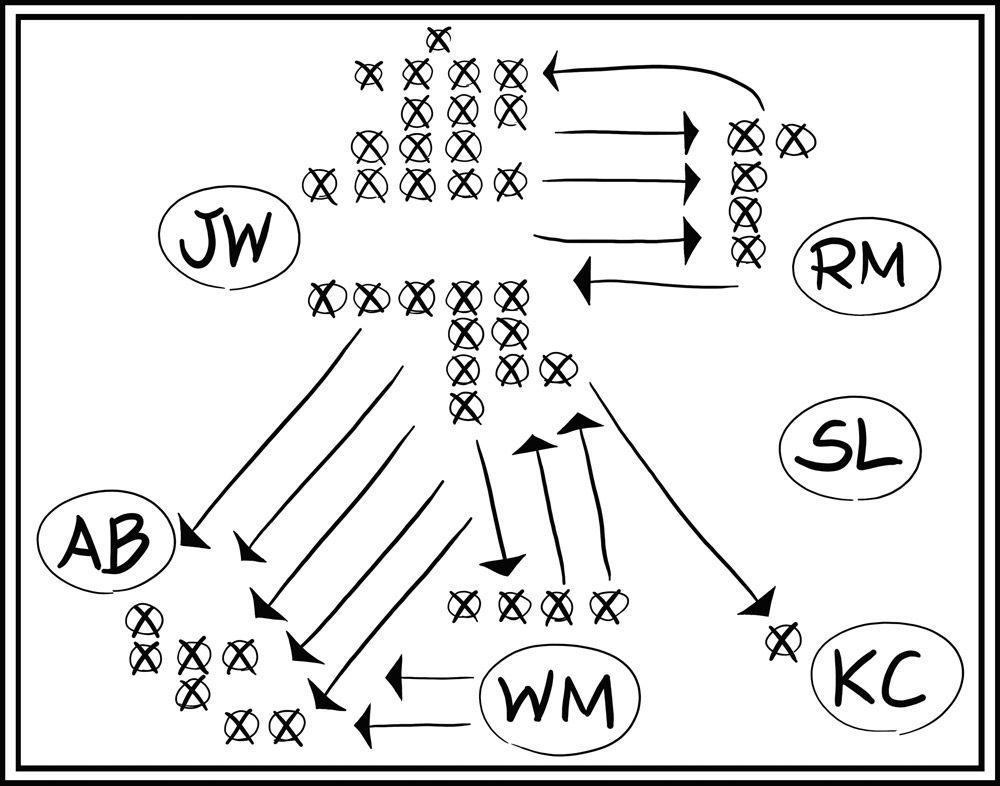

In your next meeting, cut through the clutter of comments with a map that can help reveal the group’s social cartography. Draw a diagram of where each person in the meeting is sitting. When the session begins, note who speaks first by marking an X next to that person’s name. Then each time someone speaks, add an X next to that name. If someone directs her comments to a particular person rather than to the whole group, draw a line from the speaker to the recipient. When the meeting is done you’ll get a visual representation of who’s talking the most, who’s sitting out, and who’s the target of people’s criticisms or blandishments. You can even do this for those increasingly ubiquitous conference calls. (In fact, it’s easier because nobody can see you!) Below is an example, which shows that the person with the initials JW talked the most, that many of the comments were directed at AB, and that SL and KC barely participated.

2. Mood Map

To gain a clear sense of a particular context, try mapping how it changes over time. For instance, in a meeting that involves moving others, note the mood at the beginning of the session. On a scale of 1 (negative and resistant) to 10 (positive and open), what’s the temperature? Then, at what you think is the midpoint of the meeting, check the mood again. Has it improved? Deteriorated? Remained the same? Write down that number, too. Then do the same at the very end. Think of this as an emotional weather map to help you figure out whether conditions are brightening or growing stormier. With attunement, you don’t have to be a weatherman to know which way the wind blows.

Play “Mirror, mirror.”

How attuned are you to slight alterations in appearances or situations? This team exercise, a favorite of change management consultants, can help you answer those questions and begin to improve. Gather your group and tell them to do the following:

- Find a partner and stand face-to-face with that person for thirty seconds.

- Then turn around so that you’re both back-to-back with your partner.

- Once turned around, each person changes one aspect of his or her appearance—for example, remove earrings, add eyeglasses, untuck your shirt. (Important: Don’t tell people what you’re going to ask them to do until they’re back-to-back.) Wait sixty seconds.

- Turn back around and see if you or your partner can tell what has changed.

- Repeat this twice more with the same person, each time altering something new about your appearance.

When you’re done, debrief with a short discussion. Which changes did people notice? Which eluded detection? How much of doing this well depended on being observant and attuned from the outset? How might this experience change your next encounter with a colleague, client, or student?

Find uncommon commonalities.

The research of Arizona State University social psychologist Robert Cialdini, some of which I’ll discuss in Chapter 6, shows that we’re more likely to be persuaded by those whom we like. And one reason we like people is that they remind us of . . . us.

Finding similarities can help you attune yourself to others and help them attune themselves to you. Here’s an exercise that works well in teams and yields some insights individuals can later deploy on their own.

Assemble a group of three or four people and pose this question: What do we have in common, either with another person or with everyone? Go beyond the surface. For example, does everybody have a younger brother? Have most people visited a Disney property in the last year? Are some people soccer fanatics or opera buffs or amateur cheese makers?

Set a timer for five minutes and see how many commonalities you can come up with. You might be surprised. Searching for similarities—Hey, I’ve got a dachshund, too!—may seem trivial. We dismiss such things as “small talk.” But that’s a mistake. Similarity—the genuine, not the manufactured, variety—is a key form of human connection. People are more likely to move together when they share common ground.

5.