To Sell Is Human: The Surprising Truth About Moving Others (5 page)

Read To Sell Is Human: The Surprising Truth About Moving Others Online

Authors: Daniel H. Pink

Tags: #Psychology, #Business

The numbers are staggering. According to MIT’s

Technology Review

, “In 1982, there were 4.6 billion people in the world, and not a single mobile-phone subscriber. Today, there are seven billion people in the world—and six billion mobile cellular-phone subscriptions.”

12

Cisco predicts that by 2016, the world will have more smartphones (again, handheld minicomputers) than human beings—ten billion in all.

13

And much of the action will be outside North America and Europe, powered “by youth-oriented cultures in . . . the Middle East and Africa.”

14

When everyone, not just those in Tokyo and London but also those in Tianjin and Lagos, carries around her own storefront in her pocket—and is just a tap away from every other storefront on the planet—being an entrepreneur, for at least part of one’s livelihood, could become the norm rather than the exception. And a world of entrepreneurs is a world of salespeople.

Elasticity

Now meet another guy who runs a company—Mike Cannon-Brookes. His business, Atlassian, is older and much larger than Brooklyn Brine. But what’s happening inside is both consistent with and connected to its tinier counterpart.

Atlassian builds what’s called “enterprise software”—large, complex packages that businesses and governments use to manage projects, track progress, and foster collaboration among employees. Launched a decade ago by Cannon-Brookes and Scott Farquhar upon their graduation from Australia’s University of New South Wales, Atlassian now has some twelve hundred customers in fifty-three countries—among them Microsoft, Air New Zealand, Samsung, and the United Nations. Its revenue last year was $100 million. But unlike most of its competitors, Atlassian collected that entire amount—$100,000,000.00 in sales—

without a single salesperson

.

Selling without a sales force sounds like confirmation of the “death of a salesman” meme. But Cannon-Brookes, the company’s CEO, sees it differently. “We have no salespeople,” he told me, “because in a weird way, everyone is a salesperson.”

Enter the second reason we’re all in sales now: Elasticity—the new breadth of skills demanded by established companies.

Cannon-Brookes draws a distinction between “products people buy” and “products people are sold”—and he prefers the former. Take, for instance, how the relationship between Atlassian and its customers begins. In most enterprise software companies, a company salesperson visits potential customers prospecting for new business. Not at Atlassian. Here potential customers typically initiate the relationship themselves by downloading a trial version of one of the company’s products. Some of them then call Atlassian’s support staff with questions. But the employees who offer support, unlike a traditional sales force, don’t tempt callers with fast-expiring discounts or badger them to make a long-term commitment. Instead, they simply help people understand the software, knowing that the value and elegance of their assistance can move wavering buyers to make a purchase. The same goes for engineers. Their job, of course, is to build great software—but that demands more than just slinging code. It also requires discovering customers’ needs, understanding how the products are used, and building something so unique and exciting that someone will be moved to buy. “We try to espouse the philosophy that everyone the customer touches is effectively a salesperson,” says Cannon-Brookes.

At Atlassian, sales—in this case, traditional sales—isn’t anyone’s job. It’s everyone’s job. And that paradoxical arrangement is becoming more common.

Palantir is an even larger company. Based in Palo Alto, California, with offices around the world, it develops software that helps intelligence agencies, the military, and law enforcement integrate and analyze their data to combat terrorism and crime. Although Palantir sells more than a quarter-billion dollars’ worth of its software each year, it doesn’t have any salespeople either. Instead, it relies on what it calls “forward-deployed engineers.” These techies don’t create the company’s products—at least not at first. They’re out in the field, interacting directly with customers and making sure the product is meeting their needs. Ordinarily, that sort of job—handholding the customer, ensuring he’s happy—would go to an account executive or someone from the sales division. But Shyam Sankar, who directs Palantir’s band of forward-deployed engineers, has at least one objection to that approach. “It doesn’t work,” he told me.

The more effective arrangement, he says, is “to put real computer scientists in the field.” That way, those experts can report back to home-base engineers on what’s working and what’s not and suggest ways to improve the product. They can tackle the customer’s problems on the spot—and, most important, begin to identify new problems the client might not know it has. Interacting with customers around problems isn’t selling per se. But it sells. And it forces engineers to rely on more than technical abilities. To help its engineers develop such elasticity, the company doesn’t offer sales training or march recruits through an elaborate sales process. It simply requires every new hire to read two books. One is a nonfiction account of the September 11 attacks, so they’re better attuned to what happens when governments can’t make sense of information; the other is a British drama instructor’s guide to improvisational acting, so they understand the importance of nimble minds and limber skills.

*

In short, even people inside larger operations like Atlassian and Palantir must work more like the shape-shifting pickle-maker Shamus Jones. This marks a significant change in the way we do business. When organizations were highly segmented, skills tended to be fixed. If you were an accountant, you did accounting. You didn’t have to worry about much outside your domain because other people specialized in those areas. The same was true when business conditions were stable and predictable. You knew at the beginning of a given quarter, or even a given year, about how much and what kind of accounting you’d need to do. However, in the last decade, the circumstances that gave rise to fixed skills have disappeared.

A decade of intense competition has forced most organizations to transform from segmented to flat (or at least, flatter). They do the same, if not greater, amounts of work than before—but they do it with fewer people who are doing more, and more varied, things. Meantime, underlying conditions have gone from predictable to tumultuous. Inventors with new technologies and upstart competitors with fresh business models regularly capsize individual companies and reconfigure entire industries. Research In Motion, maker of the BlackBerry, is a legend one day and a laggard the next. Retail video rental is a cash cow—until Netflix carves the industry into flank steak. All the while, the business cycle itself swooshes without much warning from unsustainable highs to unbearable lows like some satanic roller coaster.

A world of flat organizations and tumultuous business conditions—and that’s our world—punishes fixed skills and prizes elastic ones. What an individual does day to day on the job now must stretch across functional boundaries. Designers analyze. Analysts design. Marketers create. Creators market. And when the next technologies emerge and current business models collapse, those skills will need to stretch again in different directions.

As elasticity of skills becomes more common, one particular category of skill it seems always to encompass is moving others. Valerie Coenen, for instance, is a terrestrial ecologist for an environmental consulting firm in Edmonton, Alberta. Her work requires high-level and unique technical skills, but that’s only the start. She also must submit proposals to prospective clients, pitch her services, and identify both existing and potential problems that she and her firm can solve. Plus, she told me, “You must also be able to sell your services within the company.” Or take Sharon Twiss, who lives and works one Canadian province to the west. She’s a content strategist working on redesigning the website for a large organization in Vancouver. But regardless of the formal requirements of her job, “Almost everything I do involves persuasion,” she told me. She convinces “project managers that a certain fix of the software is a priority,” cajoles her colleagues to abide by the site’s style guide, trains content providers “about how to use the software and to follow best practices,” even works to “get my own way about where we’re going for lunch.” As she explains, “People who don’t have the power or authority from their job title have to find other ways to exert power.” Elasticity of skills has even begun reshaping job titles. Timothy Shriver Jr. is an executive at The Future Project, a nonprofit that connects secondary school students with interesting projects to adults who can coach them. His work reaches across different areas—marketing, digital media, strategy, branding, partnerships. But, he says, “The common thread is activating people to move.” His title? Chief Movement Officer.

And even those higher on the org chart find themselves stretching. For instance, I asked Gwynne Shotwell, president of the private space transportation firm Space Exploration Technologies Corporation (SpaceX), how many days each week she deals with selling on top of her operational and managerial duties. “Every day,” she told me, “is a sales day.”

Ed-Med

Larry Ferlazzo and Jan Judson are a husband and wife who live in Sacramento, California. They don’t pickle cucumbers or parse code. But they, too, represent the future. Ferlazzo is a high school teacher, Judson a nurse-practitioner—which means that they inhabit the fastest-growing job sector of the United States and other advanced economies.

One way to understand what’s going on in the world of work is to look at the jobs people hold. That’s what the U.S. Occupational Employment Statistics program, which I cited

here

, does. Twice a year, it provides an analysis of twenty-two major occupational groups and nearly eight hundred detailed occupations. But another way to understand the current state and future prospects of the workforce is to look at the industries where those jobs emerge. For that, we go to the Monthly Employment Report—and it shows a rather remarkable trend.

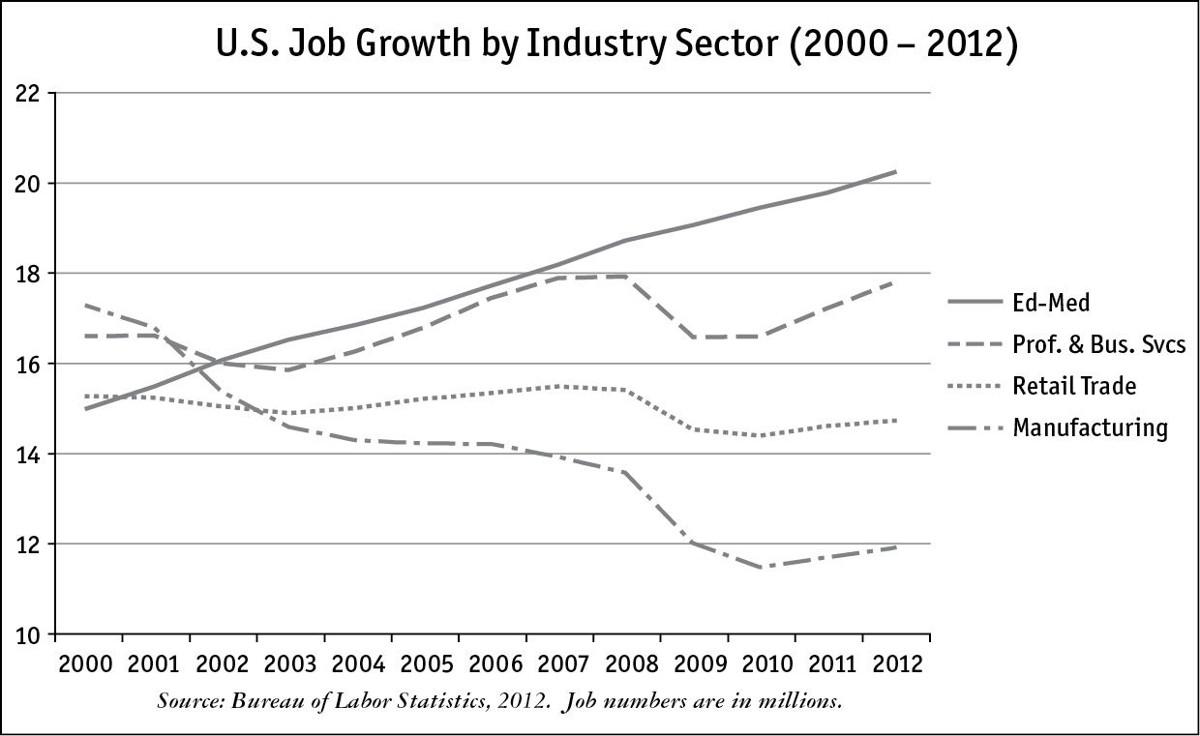

The chart below depicts what has happened so far this century to employment in four sectors—manufacturing, retail trade, professional and business services (which includes law, accounting, consulting, and so on), and education and health services.

While jobs in the manufacturing sector have been declining for forty years, as recently as the late 1990s the United States still employed more people in that sector than in professional and business services. About ten years ago, however, professional and business services took the lead. But their ascendance proved short-lived, because rising like a rocket was another sector, education and health services—or what I call Ed-Med. Ed-Med—which includes everyone from community college instructors to proprietors of test prep companies and from genetic counselors to registered nurses—is now, by far, the largest job sector in the U.S. economy, as well as a fast-growing sector in the rest of the world. In the United States, Ed-Med has generated significantly more new jobs in the last decade than all other sectors combined. And over the next decade, forecasters project, health care jobs alone will grow at double the rate of any other sector.

15

At its core, Ed-Med has a singular mission. “As teachers, we want to move people,” Ferlazzo, who teaches English and social studies in Sacramento’s largest inner-city high school, told me. “Moving people is the majority of what we do in health care,” added his nurse-practitioner wife.

Education and health care are realms we often associate with caring, helping, and other softer virtues, but they have more in common with the sharp-edged world of selling than we realize. To sell well is to convince someone else to part with resources—not to deprive that person, but to leave him better off in the end. That is also what, say, a good algebra teacher does. At the beginning of a term, students don’t know much about the subject. But the teacher works to convince his class to part with resources—time, attention, effort—and if they do, they will be better off when the term ends than they were when it began. “I never thought of myself as a salesman, but I have come to the realization that we all are,” says Holly Witt Payton, a sixth-grade science teacher in Louisiana. “I’m selling my students that the science lesson I’m teaching them is the most interesting thing ever,” which is something Payton firmly believes. The same is true in health care. For instance, a physical therapist helping someone recover from injury needs that person to hand over resources—again, time, attention, and effort—because doing so, painful though it can be, will leave the patient healthier than if he’d kept the resources to himself. “Medicine involves a lot of salesmanship,” says one internist who prefers not to be named. “I have to talk people into doing some fairly unpleasant things.”

16

Of course, teaching and healing aren’t the same as selling electrostatic carpet sweepers. The

outcomes

are different. A healthy and educated population is a public good, something that is valuable in its own right and from which we all benefit. A new carpet sweeper or gleaming Winnebago, not so much. The

process

can be different, too. “The challenge,” says Ferlazzo, “is that to move people a large distance and for the long term, we have to create the conditions where they can move themselves.”