The Sugar King of Havana (33 page)

Read The Sugar King of Havana Online

Authors: John Paul Rathbone

León signed the deal on Lobo’s behalf at Loeb’s New York apartment on Fifth Avenue on New Year’s Eve, 1957. Lobo’s option to buy the Hershey property expired at midnight, so at 11:50 p.m. one of Loeb’s lawyers stood up and stopped the hands on the clock that hung on the wall. When the agreement was finally signed, the lawyer turned the clock back on and ten minutes later it rang twelve times. It was four o’clock in the morning, and all the lawyers rose from the table dressed in black tie to toast the New Year. It would be Batista’s last in Cuba.

HAVANA WAS IMBUED with a kind of fairyland atmosphere the following year. The city was as beautiful as ever, despite a clampdown on many festivities and the growing rebel offensives. Castro’s voice could be heard regularly on clandestine Radio Rebelde broadcasts. Yet, although bookings were down, there were still droves of tourists that winter season. Two weeks before Christmas 1958, society columnist Cholly Knickerbocker wrote in his regular Smart Set column for the

New York Herald

that his whole weekend in Havana had been “disgustingly quiet. The only real danger we faced was when our golf partner almost hit us on the head with a driver . . . and when we slipped and fell on our face trying to outlast Ambassador Porfirio Rubirosa in a bongo contest.” Rubirosa—Dominican playboy, polo player, and racing driver—had been appointed ambassador to Havana the year before. El Encanto department store sold real Christmas trees at 85 cents a foot, and Christmas lights were everywhere, with hot-faced Santa Clauses ringing bells on street corners. Christmas lunch at the house of Helena Lobo was the usual family affair, full of laughter. Still, Havana was tense with rumors. “There is a mood of expectation and inevitability in the air,” my mother wrote in her diary.

New York Herald

that his whole weekend in Havana had been “disgustingly quiet. The only real danger we faced was when our golf partner almost hit us on the head with a driver . . . and when we slipped and fell on our face trying to outlast Ambassador Porfirio Rubirosa in a bongo contest.” Rubirosa—Dominican playboy, polo player, and racing driver—had been appointed ambassador to Havana the year before. El Encanto department store sold real Christmas trees at 85 cents a foot, and Christmas lights were everywhere, with hot-faced Santa Clauses ringing bells on street corners. Christmas lunch at the house of Helena Lobo was the usual family affair, full of laughter. Still, Havana was tense with rumors. “There is a mood of expectation and inevitability in the air,” my mother wrote in her diary.

She had flown down from New York in early December for the holidays. New Year’s Eve found her at the Isle of Pines, one hundred kilometers south of the Cuban mainland, with a group of friends for the opening of a swank hotel built by Manuel Ángel González del Valle, María Esperanza’s husband. American guests had come from New York for the occasion, with two waiters borrowed from the 21 Club. My mother sat by the pool, drinking daiquiris, listening to a portable radio, and discussed the situation with her friends. “I am amazed at the irresponsibility, un-awareness and frivolity which took us there,” she later remembered. “I felt quite strongly that Batista had to go but I don’t think for a moment I gave a serious thought to the country; I fear my main concern was to have a good time.”

That night, Cubans celebrated the New Year with their usual gusto. On the radio, CMQ broadcast a special all-night program, featuring music by Machito, Orquesta Aragón, and Beny Moré, the “barbarian of rhythm.” Sometime after one o’clock in the morning, an airplane rose over the roofs of Vedado, flying low. It made several slow turns overhead and banked sharply to the east and disappeared. With it went Batista. A few hours before, he had gathered with his chiefs of staff at the Camp Columbia military base and, after a short meeting, unexpectedly resigned from the presidency. As Batista boarded the plane, his incongruous last words on Cuban soil were

¡Salud! ¡Salud!

—good health and good luck. My mother, learning the surprise news on the radio, felt jubilant that Castro was victorious but, amid the luxurious setting of a foreign-owned hotel filled with American tourists at the outbreak of revolution, also in the wrong place.

¡Salud! ¡Salud!

—good health and good luck. My mother, learning the surprise news on the radio, felt jubilant that Castro was victorious but, amid the luxurious setting of a foreign-owned hotel filled with American tourists at the outbreak of revolution, also in the wrong place.

No one had expected Batista to capitulate so suddenly, although he had lost nearly all his support. Immediately after the attack on the Presidential Palace eighteen months before, Batista had managed to conjure up a Who’s Who of Cuban business leaders to appear on his balcony to applaud his survival—although Pepín Bosch, chairman of Bacardi, and Lobo were both notable for their absence. Now those same businessmen were demanding his resignation. The United States had also instituted an arms embargo. Meanwhile, Batista’s army was demoralized and ineffective, more interested in graft than counterinsurgency. As for the 300,000 people who had once cheered Batista from the square below his balcony, soon they would be shouting

¡Viva Castro!

¡Viva Castro!

Castro—only thirty-two years old, the son of a wealthy landowner in eastern Cuba—had by now spent two years in the Sierra, sustained by discipline, shrewdness, and great courage. He had also been lucky, not least in the accidental elimination of so many rivals—from the botched Palace attack and subsequent death of the Revolutionary Directorate’s leader, José Antonio Echeverría, then better known than Castro, to the killing two months later of Frank País, Castro’s most important rival in the 26 July movement. Batista had launched a last offensive in the Sierra that summer; after it failed, the rebels operated with impunity around Santiago. In August, Castro had dispatched Guevara west with a small column of men. By December they had reached Santa Clara, the major transport and communications hub of central Cuba. There were other rebel groups fighting at the end of 1958. But it was Castro and the 26 July movement that had captured the popular imagination.

The country changed overnight. In Havana, movie star George Raft was on floor duty at the Hotel Capri when news of Batista’s departure began to spread. As the night’s New Year festivities were winding down, he went up to his suite where his girlfriend, recent winner of the Miss Cuba contest, waited half-asleep.

“

Feliz año nuevo

,” I said as I got between my silk sheets, alongside this fantastic girl. In the middle of this beautiful scene—suddenly—machine-gun fire! And what sounds like cannons! I phoned down to the desk. “This is Mr. Raft,” I said. “What’s going on down there?” The operator answered, but I could hardly hear her—there was so much commotion. Finally, I made out what she was saying. “Mr. Raft, the Revolution is here. Fidel Castro has taken over everything . . . Batista has left the country!”

Feliz año nuevo

,” I said as I got between my silk sheets, alongside this fantastic girl. In the middle of this beautiful scene—suddenly—machine-gun fire! And what sounds like cannons! I phoned down to the desk. “This is Mr. Raft,” I said. “What’s going on down there?” The operator answered, but I could hardly hear her—there was so much commotion. Finally, I made out what she was saying. “Mr. Raft, the Revolution is here. Fidel Castro has taken over everything . . . Batista has left the country!”

The next day, looters appeared on Havana’s streets, smashing parking meters and casinos, much as happened when Machado had fled twenty-six years before. The Sans Souci casino was torched, and a truckload of pigs was left to run through Lansky’s gambling emporium, the Riviera. But the initial spasm of violence died down quickly, and when it became clear there would be no pandemonium, joyous Habaneros flooded the streets.

Castro began a slow triumphal march west from Santiago across the island, the television coverage providing many Cubans with their first glimpse of their new leader. His journey, ironically, coincided with the feast of Epiphany, the Christian celebration of the revelation of God made man.

Wearing crumpled olive fatigues and an open shirt with a medallion to the Virgen de la Caridad del Cobre around his neck, Castro arrived in Havana on January 8, riding through delirious flag-decked streets atop a tank. The bravery of the rebels, conquerors of the army of a nation, recalled a heroic era that predated even that of Martí—the conquistadores. Thus Lobo told journalists that Castro’s victory could “only be compared” to the audacious conquest of Peru by the Spanish conquistador Francisco Pizarro, another “adventure undertaken by a small group of men in which few people had faith.” Did Lobo think the rebels were Communist as sometimes rumored? he was asked. “I don’t believe so,” he replied. “With honesty, ability and progressiveness . . . Cuba will become one of the richest and best developed nations in the world.” Pepín Bosch, the chairman of Bacardi, was similarly enthusiastic. Returning from exile in Mexico, he told reporters at the airport, “The triumph of the revolution makes me very happy. . . . Although it may not appear so, it had the support of almost all the Cuban people.” That evening, as Castro gave his first major public address in Havana to an almost hysterically happy crowd, a white dove landed on his shoulder, an omen of peace.

In fact, few in or outside Cuba knew much about Castro. “We did not know who Fidel was,” as Lobo said. “But we knew who Batista was and we were against him and for any new democratic regime.” Apart from Castro’s magnetism, rousing oratory, and idolization of Martí, his politics—as Eisenhower’s watch-and-wait approach showed—were vague. At first Castro asked for no spoils for himself, only assuming the post of head of the army. The new government was also reassuringly stacked with middle-class and pro-business anti-Communists: the prime minister, José Miró Cardona, was even president of the Havana Bar Association. The show trials of Batistianos accused of war crimes, however, held in the sports stadium and broadcast live on television, threw a dark shadow. By May, more than five hundred had been shot. But in Washington, CIA director Allen Dulles excused the executions as a safety valve for bottled-up emotions. And in Cuba, Rufo López-Fresquet, the U.S.-educated finance minister, scolded one persistent U.S. reporter: “Instead of criticizing the executions, you ought to be doing everything you can to support our new government. We’ve just had the only non-Communist revolution of the 20th century.”

There were other warning signs. The satirical magazine

Zig-Zag

ran a cartoon poking fun at the sycophants that surrounded Castro, who demanded an immediate apology and threatened to close the publication down. Miró Cardona, the prime minister, also resigned in February, recommending that Castro become premier instead. (“I resigned. Cuba did not protest; it accepted, it applauded,” he later said.) On April 6, Lobo went to the Ministry of Finance to pay a $450,000 advance on his taxes to support the new government, as many other businessmen had done. Outside the building on O’Reilly Street in Old Havana, journalists again asked him what he thought of the new government. This time Lobo was more circumspect in his support and referred to the troubled Banco de Fomento Comercial he had bought for $500,000 the week before. “That can only be taken as a sign of confidence,” he replied elliptically.

Zig-Zag

ran a cartoon poking fun at the sycophants that surrounded Castro, who demanded an immediate apology and threatened to close the publication down. Miró Cardona, the prime minister, also resigned in February, recommending that Castro become premier instead. (“I resigned. Cuba did not protest; it accepted, it applauded,” he later said.) On April 6, Lobo went to the Ministry of Finance to pay a $450,000 advance on his taxes to support the new government, as many other businessmen had done. Outside the building on O’Reilly Street in Old Havana, journalists again asked him what he thought of the new government. This time Lobo was more circumspect in his support and referred to the troubled Banco de Fomento Comercial he had bought for $500,000 the week before. “That can only be taken as a sign of confidence,” he replied elliptically.

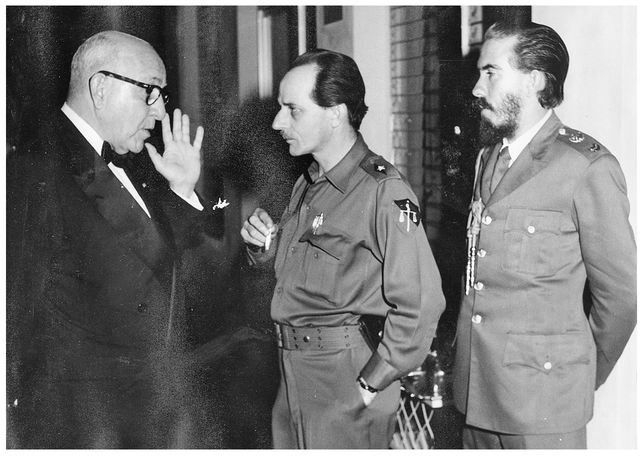

For Lobo, the new regime offered a chance for Cuba to realize a long-held vision. Since the Hershey purchase a year ago, he had continued to argue that Cuba needed to revamp its tired sugar industry, economic backbone of the country. Now he pushed for a “total but gradual” modernization. “We must modernize or die, although this must not bring joblessness,” he said. His mills, Lobo added, were already looking for new ways of cultivating sugar while also searching for new nonsugar uses for cane. These new industries—such as plastics—would then be “used to provide new jobs and year-round employment.” It was the Cuban Holy Grail: diversification away from sugar. Lobo pressed home the point later that month at a cocktail party at the Country Club, hosted by the Japanese ambassador. Dressed in black tie, he spent much of the evening talking intently to Humberto Sorí Marín, then minister of agriculture, who had acted as Castro’s legal adviser in the Sierra. Sorí Marín would shortly quarrel with Castro and eventually be executed for treason. That, however, was still two years in the future, and if he and Lobo failed to see the direction in which Castro was steering the country, so did many others.

In late April, Castro left Cuba for a two-week victory lap around the United States, invited by the association of U.S. newspaper editors. The entourage consisted of his most conservative and pro-U.S. advisers, his more radical brother Raúl and Guevara remaining behind. Dressed in olive fatigues, Castro gave a well-received speech at the National Press Club in Washington, D.C. He spoke before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and paid homage to the Lincoln and Jefferson memorials. Eisenhower had arranged to be out of town, so Castro met with Richard Nixon, then vice president. They talked privately for two and a half hours in the Capitol building and afterward were polite about each other, al-though the meeting had not gone well. Nixon later told Eisenhower that Castro was either a Communist or he was a dupe, “incredibly naïve.” Castro continued his tour, lionized by the press wherever he went, and gave a speech to rapturous applause at Princeton. Afterward, he met with a senior CIA official, Gerry Drecher, who finished their three-hour conversation convinced that Castro was an “anti-Communist.”

Lobo talks to Humberto Sorí Marín, then minister of agriculture in the new government but executed two years later for treason. Havana, March 1959.

Still, by that summer a progressive revolution was in full swing. Castro returned to Havana on May 7, and shortly thereafter signed the Agrarian Reform into law. It was the centerpiece of the government’s legislative agenda and followed a reduction in rent and utility rates in March. The bill proscribed any estate larger than 995 acres, with any excess liable to expropriation, to be repaid with long-dated bonds. A progressive tax reform followed soon after. Castro may have ominously told his finance minister after signing the tax law: “Maybe when the time comes to apply the law, there won’t be any taxpayers.” But at rallies Cubans of all ages chanted “With Fidel, with Fidel, always with Fidel” to the tune of “Jingle Bells,” and few businessmen yet protested. Despite some private misgivings, they supported the government’s plans. Even the conservative newspaper

Diario de la Marina

endorsed the land reform.

Diario de la Marina

endorsed the land reform.

Other books

3 Panthers Play for Keeps by Clea Simon

This Book is Full of Spiders by David Wong

A Thorn in the Bush by Frank Herbert

The Winds of Autumn by Janette Oke

The Dream Sanctum: Beyond The End by Solo, Kay

The Bloodied Cravat by Rosemary Stevens

Going Home by Angery American

A Place of Safety by Natasha Cooper

Mistwalker by Terri Farley

Heart of Gold by Beverly Jenkins