The Sugar King of Havana (29 page)

Read The Sugar King of Havana Online

Authors: John Paul Rathbone

Banco Financiero. Havana, c. 1958.

Lobo meanwhile convalesced in Havana after his heart attack. “I know now the time has come to relax and slow down,” he wrote to Lillian Fontaine that summer. “I was traveling on the highway of life at a breathtaking speed and in so doing could neither heed nor appreciate the landscape. Now I can take my blinkers off and leisurely enjoy the vista. . . . I am glad and relieved. That is my compensation.”

Lobo had been reading Ralph Waldo Emerson, the New England transcendental philosopher, patron of Walt Whitman and friend of Thoreau. In his essay “Compensation,” Emerson had developed the idea of a spiritual ledger, with debits and credits, and had advised the reader: “If you are wise, you will dread a prosperity which only loads you with more. . . . For every benefit which you receive, a tax is levied. He is great who confers the most benefits. He is base who receives favors and renders none.”

As Lobo lay in bed, reading Emerson and ruminating about his future, rumors began to spread that he was about to give away his fortune and meditate on life as a monk in Tibet.

“The idea might seem fantastic to a public that only knows Lobo for his implacable business sense,” gossiped one society writer. But “it would not be the first time that a man, known for being hard, ambitious and implacable in the business jungle, should decide to end his days with an act of contrition in a place that is fitting for meditation on the human condition and the uselessness and difficulties of finding happiness through wealth.”

It was also closer to the truth than many imagined. “The life I had been living could hardly be called life, looking at it retrospectively,” Lobo had written to his new love interest, Varvara Hasselbalch, a Danish aristocrat, on October 15. “I hope that my chances will be better this time and that it will enable me to live life to the fullest.”

It was only a passing fancy. Even as he recuperated, Lobo admitted to a growing restlessness and continued to act on it—just as he had in 1947 when he had orchestrated the hostile takeover attempt of Cuba Company from a hospital bed in the United States. It was as if the sugar business that ran in his veins made rest impossible. Constant physical pain also goaded him on.

“I’ve been in pain for so long now that I don’t think I remember a day in the past seven odd years, when I was machine gunned, that I have not suffered physical pain of some nature or another,” he wrote to Lillian Fontaine later that year.

“I know that pain can either destroy a person or build up his moral substance to something akin to granite. Probably I have achieved certain goals and ambitions because my good friend

pain

was always with me. I really think I should miss him if he were to desert me today.”

pain

was always with me. I really think I should miss him if he were to desert me today.”

In January 1954, Lobo closed negotiations to buy the mill Araújo, signing the deeds from inside an oxygen tent. A telephone by his bedside kept him in touch with the daily ups and downs of the international sugar market. It made for a ghoulish scene: the stricken millionaire, supposedly at death’s door, unable to desist from his schemes. On February 14, Leonor wrote her father a fitting ditty, “To the Proud Owner of Central Araújo on Valentine’s Day”:

In the oxygen tent he buys his mills,

While taking his cardiograms and pills.

He swears to retire when he feels “the oppression,”

But market maneuvering is

still

the obsession . . .

While taking his cardiograms and pills.

He swears to retire when he feels “the oppression,”

But market maneuvering is

still

the obsession . . .

Lobo lightened the mood further with gallows humor in a letter to Varvara, in which he detailed his plans and invited her to come stay in Cuba. “As Jonah said to the whale,” he wrote, “you can’t keep a good man down.”

VARVARA HASSELBALCH, the great-granddaughter of the Russian princess Varvara Sergeievna, arrived in Havana on March 25, 1954. She had met Lobo two years before at a dinner party in New York. A photographer who worked in Africa and Europe, she had been decorated during the Second World War for her bravery as a frontline ambulance driver. She was also twenty years younger than Lobo and, standing well over six feet in her high heels, several inches taller. Of all the guests that night, though, “Lobo was by far the most fascinating,” she told me. It was Lobo’s sense of humor that attracted her, she said, his cannon-black eyes, and his intelligence. “He always had something turning in his mind, some idea or other. That was what made him so captivating.”

I had gone to see her in Copenhagen on a bleak January afternoon when a sharp north wind had emptied the city’s streets. Snow scudded over the threshold as Varvara opened the door of her apartment on the second floor of a solid stone building. Eighty-six years old, she wore gold lamé trousers, shiny silver pumps, and a white T-shirt with “CUBA” stenciled across the front. “It’s in honor of you, my dear,” she explained with aplomb, ushering me inside.

With her flamboyant dress sense, smoker’s voice, and ribald sense of humor, Varvara is sometimes referred to in her native Denmark as the country’s “Dame Edna,” after the cross-dressing comedienne and satirist. Her rooms were an Aladdin’s cave of exotic souvenirs. Books, papers, gold ash-trays, and kitsch gadgets were piled on side tables. Portraits of Russian ancestors hung on the walls, as well as the head of a deer with a tiara perched on its antlers, while a mannequin stood in one corner wearing a burka. I followed Varvara as she made for the kitchen, pushing a walker as though it were a lawnmower, clearing an open trail of red carpet through the imperial bric-a-brac. She settled at a table under a garden umbrella, fairy lights and plastic flowers threaded among its frets, and pushed a button. The lights twinkled and birdsong warbled from speakers hidden around the room. “Ahh, my little Tivoli,” she said with a triumphant sigh.

Varvara had found a somber mood prevailing when she arrived in Cuba in 1954. It was eight months after the Moncada attack, and an airport official rifled through her luggage; smuggled guns, he told her, had been discovered the week before. Lobo met her outside immigration dressed in his usual white linen trousers, guayabera, and black bow tie. In the car on the way into town, he said: “I’m glad you finally came, it has been so long I had almost given up hope.” His voice was softer and kinder than she remembered. Elsewhere, though, Varvara sensed threat amid the luxury and beauty.

In Havana, she was struck by the heat, by the coolness of the white marble floors at Lobo’s house, by the Vlaminck, Turner, and Utrillo paint-ings that hung on the walls of her bedroom, and by the two maids dressed in starched white pinafores who packed her clothes and suitcase away. She delighted in the blue of the swimming pool amid the lush greens and bright red flowers of the garden. She also shivered at the iron grilles on the windows and the heavy front door that had closed behind her with a clunk.

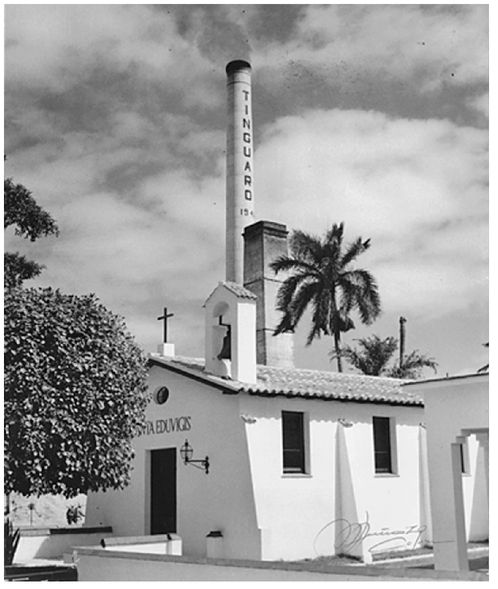

Varvara’s photograph of Tinguaro’s

batey,

1954.

batey,

1954.

Lobo took her on a tour of his mills. At the beach at Tánamo, Varvara shied away “like a coward” from swimming, worried that the wire netting stretched across the mouth of the bay would let in sharks and barracudas from the open sea. At Pilón, Varvara went horseback riding one evening with María Luisa. She was bewitched by the twilight, the inky silhouettes of palm trees that reminded her of the ruins of a Greek temple, the fields of harvested cane golden with fallen leaves, the rugged hills in the distance, and the sight of a hawk hovering over a clump of trees. Then night fell, it began to rain, she sang to keep her spirits up, and the shadow of a boy ran past, screaming as if in pain and then laughing at her from the faintly illuminated doorway of a hut.

At Tinguaro she felt that same sense of unease shading into peril. One day, Lobo suggested that she take some pictures of the mill, explaining that he had an important meeting to attend. Varvara photographed the

batey

, the two chimneys of the mill, the chapel dedicated to Lobo’s mother, and the old lamps from the Malecón. Walking back to the guesthouse, she saw a battered limousine pull up in a cloud of dust. Two men dressed in shabby guayaberas and black trousers got out in a hurry. They left soon after in an even faster rush.

batey

, the two chimneys of the mill, the chapel dedicated to Lobo’s mother, and the old lamps from the Malecón. Walking back to the guesthouse, she saw a battered limousine pull up in a cloud of dust. Two men dressed in shabby guayaberas and black trousers got out in a hurry. They left soon after in an even faster rush.

“What was all that about?” she asked, climbing the steps of the porch, where Lobo stood waiting for her in the shade.

“That was two of Batista’s men,” Lobo replied. “They picked up a check for thirty thousand dollars. We got off cheap.”

Varvara left Cuba soon after on a scheduled return flight to Portugal. Lobo had asked her to marry him before leaving. Free-spirited Varvara had prevaricated. Stopping over at New York, she met with Belle Baruch, a childhood friend and daughter of the legendary Wall Street investor Bernard Baruch. Belle was worried about her future.

“Let’s drive over and visit Father,” she told Varvara when she picked her up at the airport.

A self-made millionaire, Baruch had created his first fortune speculating in sugar stocks on Wall Street in the first decades of the century. He spent of much of his later life as “Adviser to the Presidents,” most recently Roosevelt and Truman, and the familiar newspaper photographs of Baruch cogitating on a park bench across the street from the White House somehow reassured millions of Americans that the nation’s leaders were being sensibly counseled. Baruch has been credited with originating the phrase “the Cold War,” in 1947, and his independence of mind and spirit earned him the epithet “the Lone Wolf of Wall Street.” Lobo would have approved, if not of the advice he subsequently gave Varvara.

John Foster Dulles, the U.S. secretary of state, was leaving when Varvara arrived at Baruch’s Long Island property. She found Baruch, eighty-four, in high spirits after his daily swim. While Baruch dried off in the sun, Belle began to tell him about Lobo. Baruch listened closely, turned serious, then put on his pince-nez and looked Varvara in the eye.

“A Cuban? Never! A millionaire on paper, maybe,” he said.

“Feather,” he called her. “You must promise me never to marry him. If it is an elderly millionaire you’re looking for I have plenty of friends I know who would more than willingly marry you.”

Belle was triumphant. “You’ll just have to listen to Father.”

Varvara was interested in Lobo, but not his money; she feared living in a gilded cage. At her apartment in Copenhagen, she showed me the five-page handwritten letter that Lobo had sent after she finally refused his marriage offer. (“Are you sure?” Lobo had cabled earlier. “Definitely,” came her reply.) I commented that she was one of the few women to have refused his attentions, and Varvara punched the air, her hands losing themselves momentarily in the plastic flowers and fairy lights above her head.

ONE HIGH-SKIED APRIL DAY I went to visit Tinguaro, now a state-owned mill like all the others in Cuba. Cresting the hill in a rented car, I saw a lush grove amid the surrounding sugar fields, with two chimneys standing clear above the trees. I had dropped off a hitchhiking accountant a mile back at the crossroads after picking her up two hours earlier at the start of the drive. Pertly made up, with red lipstick and a crisp white shirt, she had contorted herself as she dropped a small bag into the backseat, then introduced herself as Gladys, thanked me for the lift, and unrolled a litany of soft curses about the interminable wait for the bus (called

La Madre

, the mother, as there was only one). There were also the poor pay at her job, the health of her mother she was now visiting, the state of the country, and her absent boyfriend.

La Madre

, the mother, as there was only one). There were also the poor pay at her job, the health of her mother she was now visiting, the state of the country, and her absent boyfriend.

Car windows rolled down, we drove through the back roads of Matanzas, past half-started industrial projects, now roofless and rusted lumps of iron by the side of the road, the single lane of tarmac kinking through shabby former sugar towns, where clumps of people stood on street corners in the shade beside shuttered shops. Their expressions seemed marked with a bitter lassitude that I had not seen elsewhere in Cuba. “What are they waiting for?” I asked. “To die of hunger,” came Gladys’s reply, a remark that triggered the memory of a cane cutter I’d picked up on another drive, a wiry and rangy-looking man with a gravelly voice, who had commented sourly when a boxy Lada had overtaken us on the highway, driven by what he took to be a party functionary: “See that man? He eats a lot of

meat

.”

meat

.”

I had wanted to visit Tinguaro in the hope I would find some shard of Lobo’s life that might help conjure up the past. What I had not expected was a day so joyously beautiful. The hum of the car wheels on the road, the warm breeze, and the tawny fields of uncut sugarcane soon lulled Gladys and me into silence. After she again twisted around in her seat to retrieve her bag and waved goodbye from the side of the road, I drove into the peaceful view of the old mill in front of me and pulled up through open gates into Tinguaro’s

batey

. There the greenery, the warm mid-morning light, and the birds singing in the ficus trees conjured up a sense of the beginning of things, a moment before the times of malice and misdeed.

batey

. There the greenery, the warm mid-morning light, and the birds singing in the ficus trees conjured up a sense of the beginning of things, a moment before the times of malice and misdeed.

I got down from the car, and what first caught my eye was a metal stirrup by the steps leading up to the

casa de vivienda

that Lobo’s guests had once used to scrape mud off their shoes. There were also a delicate, knee-high hooped metal railing that circled the front lawn, an arched hedge that rose over a walkway, wildly overgrown and shaggy with leaves, and next to it one of the streetlamps that Lobo had brought from Havana’s Malecón. Time and weather had done their work elsewhere, obliterating most other traces of the past. The trees that once shaded the house had long gone, blown down in a storm, as had the palms I had seen in my mother’s pictures. The roofs of some of the other buildings in the

batey

had fallen in, and one wing of the guesthouse had burned down and been replaced by a well-tended vegetable plot.

casa de vivienda

that Lobo’s guests had once used to scrape mud off their shoes. There were also a delicate, knee-high hooped metal railing that circled the front lawn, an arched hedge that rose over a walkway, wildly overgrown and shaggy with leaves, and next to it one of the streetlamps that Lobo had brought from Havana’s Malecón. Time and weather had done their work elsewhere, obliterating most other traces of the past. The trees that once shaded the house had long gone, blown down in a storm, as had the palms I had seen in my mother’s pictures. The roofs of some of the other buildings in the

batey

had fallen in, and one wing of the guesthouse had burned down and been replaced by a well-tended vegetable plot.

Other books

Christmas Miracles by Brad Steiger

Undying Desire by Jessica Lee

The Indian Burial Ground Mystery by Campbell, Julie

Hope Rising by Stacy Henrie

Highland Honor by Hannah Howell

The Stolen Suitor by Eli Easton

Swan Song by Tracey

The Way of Things by Tony Milano

How to Marry a Cowboy (Cowboys & Brides) by Carolyn Brown