The Sugar King of Havana (30 page)

Read The Sugar King of Havana Online

Authors: John Paul Rathbone

Tinguaro felt deserted. Some boys jostled around an improvised basketball hoop they had pinned to a wall near the empty kidney-shaped swimming pool that Esther Williams had once dived into and where my mother had swum. It had looked so glamorous in old photographs but was no larger than the backyard pool of so many suburban American homes, and was empty of water, blue tiles ripped off the sides.

Manolo Suárez, a swarthy man in his fifties, accompanied me while I strolled down Tinguaro’s main street, pushing a pedal bike. The chapel at the end was shut, as was the funeral parlor next door. We passed tidy workers’ houses that lined cramped but leafy walkways, their beams sagging with age. Without prompting, Manolo commented that Lobo had been much liked at Tinguaro, that he had treated people well and helped them when they needed it. Manolo’s only personal memory—a flash of glamour—was of a convertible car driving into the

batey

with Lobo sitting in the back. A local teacher added: “Yes, he was a good man; I remember everyone saying so when I was a small girl.”

batey

with Lobo sitting in the back. A local teacher added: “Yes, he was a good man; I remember everyone saying so when I was a small girl.”

Tinguaro was Lobo’s pet. He lavished attention and money on the mill and showed it off to others, like a prize cat. He ran it like a benevolent patriarch, or feudal lord, depending on your point of view. Yet he saw the weakness of such a system and thought of ways to improve it. In 1958, he sent a newspaper article from the United States to María Luisa. By then, she had left school and was working at Galbán Lobo to try to improve social conditions around Lobo’s mills; Leonor was still in the United States, working in publishing after graduating from Radcliffe. The clipping that Lobo sent to María Luisa told the story of a company lumber town in Arkansas that had turned itself over to the inhabitants. Crossett, with a population of three thousand, had flourished, the article said, when its single company owner abandoned its patriarchal system and allowed workers to choose their schools, organize their own affairs, and buy their houses using subsidized credit. “Perhaps this is the solution to Tinguaro? Or something like it,” Lobo had scribbled to María Luisa in an attached note.

Tinguaro’s founders had been progressive men too. In 1799, Don Pedro Diago had complained of Cuban sugar mills’ technical inferiority due to the negative influence of slavery. Four years later, he installed wind-powered cane grinders, following the successful example of English plant-ers in Barbados. When Don Pedro’s experiment failed—“because when there was wind there was no cane to grind, and when there was cane there was no wind,” as Lobo put it—he installed a steam engine instead, a ten-horsepower machine brought over from England. This was probably Cuba’s first commercially successful steam-powered mill, although the Conde de Montalvo, María Esperanza’s ancestor, had studied the idea a decade before. Other planters soon copied Don Pedro’s example. “If only current generations of

hacendados

imitated the same spirit of progress that inspired those planters, instead of the extraordinary slackness that characterizes our class today,” Lobo wrote disparagingly in 1958.

hacendados

imitated the same spirit of progress that inspired those planters, instead of the extraordinary slackness that characterizes our class today,” Lobo wrote disparagingly in 1958.

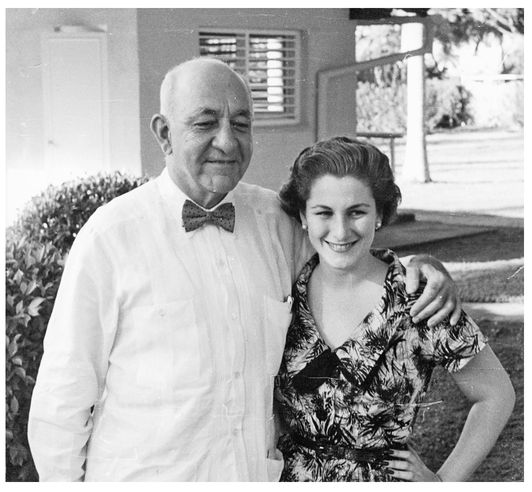

María Luisa and her father.

The mill at Tinguaro, the last of a two-hundred-year-long line of sugar mills at the site, has been dismantled now, the buildings stripped bare by trucks and cranes to salvage any reusable ironwork. All that is left are the chimneys that Varvara once photographed, stenciled with the faded slogan “THE MOST EFFICIENT OF ALL”—a cheap revolutionary irony—and some of the fretwork that held up the huge shed which once housed Lobo’s orange-painted cane grinders. Even these steel beams have collapsed at one end, leaving the roof girders bent down to the ground like the skeleton of a huge dinosaur feeding out of a trough. As chance had it, a sole cloud hovered over one of the chimneys like a puff of smoke, giving the impression that the furnaces were still working, the

zafra

in full swing. It suggested a distant if improbable hope of regeneration. Lobo, who had called the operation he rebuilt at Tinguaro “a Phoenix, rising from its ashes,” had felt a similar optimism several decades before.

zafra

in full swing. It suggested a distant if improbable hope of regeneration. Lobo, who had called the operation he rebuilt at Tinguaro “a Phoenix, rising from its ashes,” had felt a similar optimism several decades before.

Ten

AT THE ALTAR

The Americans invented wash and wear, clothes you did not need to iron. The guerillas invented patria o muerte, and you did not need to wash.

—ELADIO SECADES

I

t is in the last years of the Republic that the dissonances become sharpest—between the Cuba that so many people suppose existed before Castro came down from the Sierra and the life that my family, Lobo’s family, and their friends remember. There is so much that feels as though it needs to be said. Yet when I collect my thoughts they make an awkward collection, as if each incident or image was elbowing the one next to it in the ribs. There is no consistency. Instead, there is diversity.

t is in the last years of the Republic that the dissonances become sharpest—between the Cuba that so many people suppose existed before Castro came down from the Sierra and the life that my family, Lobo’s family, and their friends remember. There is so much that feels as though it needs to be said. Yet when I collect my thoughts they make an awkward collection, as if each incident or image was elbowing the one next to it in the ribs. There is no consistency. Instead, there is diversity.

There are the high-society parties in Havana, the men in black or white tie, the women softly abundant in bosomy dresses with deep décolletages and bare shoulders. There are also the obligatory family lunches every Sunday, the conservative social mores, the Catholicism, the decorous attention to propriety. When my mother felt hot, she was advised to “close her pores.” If she went on a date, it was with a chaperone. Like most middle- or upper-class Habaneras, my mother didn’t ride on public transport—unlike the Lobo daughters. She didn’t play in public parks or go to public schools—which were for poor people. Nor did she bathe at public beaches. Instead she went to Varadero, where the days passed in a languid routine. El Chino, the Chinaman, an itinerant portrait photographer, patrolled the white sand with his camera, wearing a pith helmet and commenting on how everyone had grown from the year before. In the evening, a record might be placed on the phonograph, the music floating out over the waves. At night a line was trailed out to sea and tied onshore to the clapper of a bell that rang out when a hooked fish started to run.

As for black Cuba, the only contact that my mother had was when María la Gorda, Fat Mary, her beloved nanny, took her by bus to a small house on the outskirts of Havana one evening. It was a dramatic if not untypical introduction for an upper-class white girl to the Santería liturgy—the drummed invocation of the spirit of African gods. Yet, even though she is in her spry mid-seventies, it is also one she can hardly remember now.

Far from the seedy downtown areas such as the Barrio Colón or the sex shows in the back streets of Chinatown, my mother’s life, like that of her peers, revolved around family gatherings and social events held in private clubs such as the Havana Yacht Club, which refused to accept Batista because he was a corrupt politician and also mulatto, which made him a social pariah. In the suburbs of Vedado, Miramar, and the Country Club, she attended a busy round of dances, sporting events, extravagant coming-out parties, and even more lavish weddings, each one carefully described the next day in the social pages of the newspapers. At the pinnacle stood the

boda del gran mundo,

the high-society wedding—none more magnificent than the 1955 marriage of Norberto Azqueta Arrandiaga to Lian Fanjul y Gómez-Mena, which united three of Cuba’s most powerful sugar families, the Fanjul-Riondas, the Gómez-Menas, and the Azquetas. “Their marriage will forever be inscribed in gold in the annals of our social history,” gushed the

Diario de la Marina

’s social diarist. Below the

boda del gran mundo

ranged the lower social heights of the

boda elegante

, the elegant wedding, only slightly less magnificent; then the

boda íntima

, with diary coverage limited to a portrait of the bride and a description of her dress; and then the lowest category of all, the

boda

, with no qualifying adjective whatsoever. The church was just as fastidious. Cardinal Manuel Arteaga y Betancourt, Havana’s archbishop, fumed about “the fashion of impudent dressing which has become more prevalent and indecent among women” and ordered that no woman attending a Cuban wedding could wear “a low-necked dress, short dress, or sleeveless dress.” If they did, the priest would suspend the ceremony.

boda del gran mundo,

the high-society wedding—none more magnificent than the 1955 marriage of Norberto Azqueta Arrandiaga to Lian Fanjul y Gómez-Mena, which united three of Cuba’s most powerful sugar families, the Fanjul-Riondas, the Gómez-Menas, and the Azquetas. “Their marriage will forever be inscribed in gold in the annals of our social history,” gushed the

Diario de la Marina

’s social diarist. Below the

boda del gran mundo

ranged the lower social heights of the

boda elegante

, the elegant wedding, only slightly less magnificent; then the

boda íntima

, with diary coverage limited to a portrait of the bride and a description of her dress; and then the lowest category of all, the

boda

, with no qualifying adjective whatsoever. The church was just as fastidious. Cardinal Manuel Arteaga y Betancourt, Havana’s archbishop, fumed about “the fashion of impudent dressing which has become more prevalent and indecent among women” and ordered that no woman attending a Cuban wedding could wear “a low-necked dress, short dress, or sleeveless dress.” If they did, the priest would suspend the ceremony.

Set against such images

,

there is the Havana most popularly remembered: the opulent Mafia-infested gambling den–cum–brothel, its beauty a decadent façade behind which languished a people mired in want. This is the Havana of the Casa de Marina—Havana’s fanciest bordello; of the “love motels” that my mother and her girlfriends would cruise by at night to see if any of their boyfriends’ cars were parked outside; and of Meyer Lansky, the Mob King, padding around an air-conditioned suite above the casino at his hotel, the Riviera. It is also the Havana of the boozy good times of American tourists boxing with maracas in their hands as they staggered back to their hotel bedrooms at night; the humiliating comment that Errol Flynn scrawled across the menu of the Bodeguita del Medio, a bohemian bar in the old town, “Best place to get drunk”; and the luxury of the Hotel Nacional, rising from its rocky Vedado bluff above the Malecón. Lansky had revamped the Nacional’s casino at Batista’s invitation and called it the Parisien, although my aunt Carmen remembers the hotel in another way. She was the daughter of the American manager, and grew up in Suite 230, “the one with the wraparound balcony on the second floor.” Her earliest memories are of getting caught among the legs of chefs and busy waiters carrying room service on silver trays, watching guests drink highballs in the Palm Court from behind the potted palms, and snooping on film stars when she hid in the closets in their rooms.

,

there is the Havana most popularly remembered: the opulent Mafia-infested gambling den–cum–brothel, its beauty a decadent façade behind which languished a people mired in want. This is the Havana of the Casa de Marina—Havana’s fanciest bordello; of the “love motels” that my mother and her girlfriends would cruise by at night to see if any of their boyfriends’ cars were parked outside; and of Meyer Lansky, the Mob King, padding around an air-conditioned suite above the casino at his hotel, the Riviera. It is also the Havana of the boozy good times of American tourists boxing with maracas in their hands as they staggered back to their hotel bedrooms at night; the humiliating comment that Errol Flynn scrawled across the menu of the Bodeguita del Medio, a bohemian bar in the old town, “Best place to get drunk”; and the luxury of the Hotel Nacional, rising from its rocky Vedado bluff above the Malecón. Lansky had revamped the Nacional’s casino at Batista’s invitation and called it the Parisien, although my aunt Carmen remembers the hotel in another way. She was the daughter of the American manager, and grew up in Suite 230, “the one with the wraparound balcony on the second floor.” Her earliest memories are of getting caught among the legs of chefs and busy waiters carrying room service on silver trays, watching guests drink highballs in the Palm Court from behind the potted palms, and snooping on film stars when she hid in the closets in their rooms.

It is because of such high jinks that Carmen maintains she is the inspiration for Eloise, the naughty six-year-old girl of Kay Thompson’s books, who grows up during the 1950s in New York’s Plaza Hotel. Eloise “skibbled” through the Plaza’s corridors, zoomed up and down its elevators, “sklonked” kneecaps, visited Paris and Moscow, where she saw that the Russians stood “in line for absolutely everything,” and made other droll pronouncements, such as “getting bored is not allowed” and “sometimes I comb my hair with a fork.” Carmen’s story may or may not be true. Still, two of the few things that she brought out of Cuba when she left the island were a browning photo of Thompson sitting in an outdoor atrium of the hotel with herself and her father, and a letter, now sadly lost, thanking Carmen’s father for the idea behind the Eloise books.

Descriptions of Cuban revolutionary fever sit incongruously next to such scenes. By the mid-1950s, Batista was on his back heels and the tradition of rival, rebel

bonches

had returned. Some operated secretly in the cities; others comprised groups of disaffected officers plotting in the army. At one point, there were even student rebels in the Presidential Palace itself. On March 13, 1957, the Revolutionary Directorate shot its way into Batista’s office on the second floor. Their leader declared in a broadcast from the CMQ radio station, seized in a separate attack: “People of Havana! The Revolution is in progress. . . . The dictator has been executed in his den!” But in Batista’s office all they found was a half-finished cup of coffee, steaming on his walnut desk; the president had escaped the attack, rising in an elevator to a sealed and guarded room on the third floor.

The

Revolution,

that

Revolution, was yet to come.

bonches

had returned. Some operated secretly in the cities; others comprised groups of disaffected officers plotting in the army. At one point, there were even student rebels in the Presidential Palace itself. On March 13, 1957, the Revolutionary Directorate shot its way into Batista’s office on the second floor. Their leader declared in a broadcast from the CMQ radio station, seized in a separate attack: “People of Havana! The Revolution is in progress. . . . The dictator has been executed in his den!” But in Batista’s office all they found was a half-finished cup of coffee, steaming on his walnut desk; the president had escaped the attack, rising in an elevator to a sealed and guarded room on the third floor.

The

Revolution,

that

Revolution, was yet to come.

The problem in bringing all these disparate images into single focus is that Cuba was, as modern tourist literature might describe it, a

Land of Contrasts!

Rural conditions could be miserable, especially in Oriente, where María Luisa saw on trips around her father’s sugar mills “the kids with swollen bellies, dirty eyes and bare feet.” There was high unemployment during the dead season after the sugar harvest ended and cane cutters were laid off. Yet 1957 was also one of the best years the Cuban economy had ever enjoyed, thanks to the Suez crisis, which drove sugar prices to a high. Indeed, if misery and want alone could cause a revolution, then the “first great patriotic, democratic and socialist revolution of the continent . . . should have been first produced in Haiti, Colombia or even Chile,” as veteran Communist Party chieftain Aníbal Escalante said in 1960. “Cuba was not one of the countries with the lowest standard of living of the masses in Latin America, but on the contrary one of those with the highest.” It had more doctors per capita than France, Holland, Japan, even England.

Land of Contrasts!

Rural conditions could be miserable, especially in Oriente, where María Luisa saw on trips around her father’s sugar mills “the kids with swollen bellies, dirty eyes and bare feet.” There was high unemployment during the dead season after the sugar harvest ended and cane cutters were laid off. Yet 1957 was also one of the best years the Cuban economy had ever enjoyed, thanks to the Suez crisis, which drove sugar prices to a high. Indeed, if misery and want alone could cause a revolution, then the “first great patriotic, democratic and socialist revolution of the continent . . . should have been first produced in Haiti, Colombia or even Chile,” as veteran Communist Party chieftain Aníbal Escalante said in 1960. “Cuba was not one of the countries with the lowest standard of living of the masses in Latin America, but on the contrary one of those with the highest.” It had more doctors per capita than France, Holland, Japan, even England.

Other books

My Brother's Keeper by Adrienne Wilder

Wingless by Taylor Lavati

The Brand by M.N Providence

TOMMY GABRINI 2: A PLACE IN HIS HEART by Monroe, Mallory

Snow Wolf: Wolves of Willow Bend (Book 9) by Heather Long

Make Me Melt by Nicki Day

Hambre by Knut Hamsun

Forbidden (Devil's Sons Motorcycle Club Book 1) by Thomas, Kathryn

Drifter's Run by William C. Dietz