The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger (10 page)

Read The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger Online

Authors: Richard Wilkinson,Kate Pickett

Tags: #Social Science, #Economics, #General, #Economic Conditions, #Political Science, #Business & Economics

In another article, Putnam says:

the causal arrows are likely to run in both directions, with citizens in high social capital states likely to do more to reduce inequalities, and inequalities themselves likely to be socially divisive.

26

Taking a more definite stance in his book,

The Moral Foundations of Trust

, Eric Uslaner, a political scientist at the University of Maryland, believes that it is inequality that affects trust, not the other way round.

27

If we live in societies with more social capital, then we know more people as friends and neighbours and that might increase our trust of people we know, people we feel are like us. But Uslaner points out that the kind of trust that is being measured in surveys such as the European and World Values Survey is trust of strangers, of people we don’t know, people who are often not like us. Using a wealth of data from different sources, he shows that people who trust others are optimists, with a strong sense of control over their lives. The kind of parenting that people receive also affects their trust of other people.

In a study with his colleague Bo Rothstein, Uslaner shows, using a statistical test for causality, that inequality affects trust, but that there is ‘no direct effect of trust on inequality; rather, the causal direction starts with inequality’.

28

,

p. 45 Uslaner says that ‘trust cannot thrive in an unequal world’ and that income inequality is the ‘prime mover’ of trust, with a stronger impact on trust than rates of unemployment, inflation or economic growth.

27

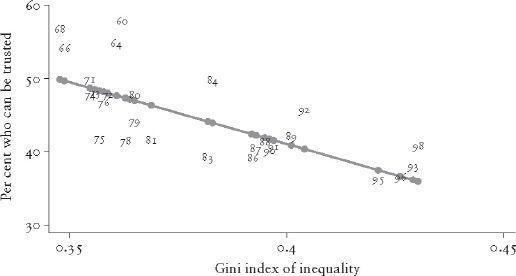

It is not average levels of economic wellbeing that create trust, but economic equality. Uslaner’s graph showing that trust has declined in the USA during a

Figure 4.3

As inequality increased, so trust declined.

27

, p. 187

period in which inequality rapidly increased, is shown in Figure 4.3. The numbers on the graph show for each year (1960–98) the relation between the level of trust and inequality in that year.

Changes in inequality and trust go together over the years. With greater inequality, people are less caring of one another, there is less mutuality in relationships, people have to fend for themselves and get what they can – so, inevitably, there is less trust. Mistrust and inequality reinforce each other. As de Tocqueville pointed out, we are less likely to empathize with those not seen as equals; material differences serve to divide us socially.

TRUST MATTERS

Both Putnam and Uslaner make the point that trust leads to cooperation. Uslaner shows that, in the USA, people who trust others are more likely to donate time and money to helping other people. ‘Trusters’ also tend to believe in a common culture, that America is held together by shared values, that everybody should be treated with respect and tolerance. They are also supportive of the legal order.

Trust affects the wellbeing of individuals, as well as the wellbeing of civic society. High levels of trust mean that people feel secure, they have less to worry about, they see others as co-operative rather than competitive. A number of convincing studies in the USA have linked trust to health – people with high levels of trust live longer.

29

In fact, people who trust others benefit from living in communities with generally high levels of trust, whereas people who are less trusting of others fare worse in such neighbourhoods.

30

Trust, or lack of it, meant the difference between life and death for some people caught up in the chaotic aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. Trust was also crucial for survival in the Chicago heatwave of 1995. Sociologist Eric Klinenberg, in his book about the heatwave,

31

showed how poor African-Americans, living in areas with low levels of trust and high levels of crime, were too frightened to open their windows or doors, or leave their homes to go to local cooling centres established by the city authorities. Neighbours didn’t check on neighbours, and hundreds of elderly and vulnerable people died. In equally poor Hispanic neighbourhoods, characterized by high levels of trust and active community life, the risk of death was much lower.

RAIDERS AND MAVERICKS

Perhaps another marker of corroded social relations and lack of trust among people was the rapid rise in the popularity of the Sport Utility Vehicle (SUV) through the 1980s and 1990s. These vehicles are known in the UK by the derogatory term ‘Chelsea tractors’ – Chelsea being a rich area of London, the name draws attention to the silliness of driving rugged off-road vehicles in busy urban areas. But the vehicles themselves have names that evoke images of hunters and outdoorsmen – Outlander, Pathfinder, Cherokee, Wrangler, etc. Others evoke an even tougher image, of soldiers and warriors, with names like Trooper, Defender, Shogun, Raider and Crossfire. These are vehicles for the ‘urban jungle’, not the real thing.

Not only did the popularity of SUVs suggest a preoccupation with looking tough, it also reflected growing mistrust, and the need to feel safe from others. Josh Lauer, in his paper, ‘Driven to extremes’, asked why military ruggedness became prized above speed or sleekness, and what the rise of the SUV said about American society.

32

He concluded that the trend reflected American attitudes towards crime and violence, an admiration for rugged individualism and the importance of shutting oneself off from contact with others – mistrust. These are not large vehicles born from a co-operative public-spiritedness and a desire to give lifts to hitch-hikers – hitch-hiking started to decline just as inequality started to rise in the 1970s. As one anthropologist has observed, people attempt to shield themselves from the threats of a harsh and untrusting society ‘by riding in SUVs, which look armoured, and by trying to appear as intimidating as possible to potential attackers’.

33

Pollster Michael Adams, writing about the contrasting values of the USA and Canada, pointed out that minivans outsell SUVs in Canada by two to one – the ratio is reversed in America (and Canada is of course more equal than America).

34

Accompanying the rise in SUVs were other signs of Americans’ increasing uneasiness and fear of one another: growing numbers of gated communities,

35

and increasing sales of home security systems.

32

In more recent years, due to the steeply rising cost of filling their fuel tanks, sales of SUVs have declined, but people still want that rugged image – sales of smaller, tough-looking ‘cross-over’ vehicles continue to rise.

WOMEN’S STATUS

In several respects, more unequal societies seem more masculine, at least in terms of the stereotypes. When we put this to the test, we found that just as levels of trust and social relations are affected by inequality, so too is the status of women.

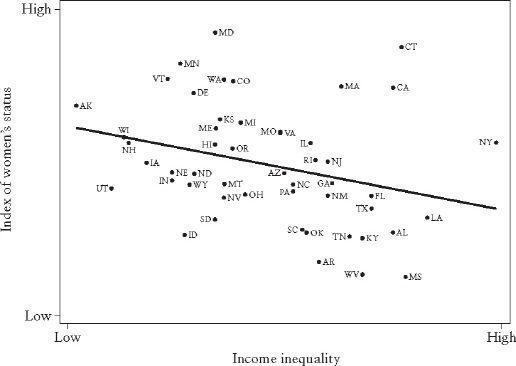

In the USA, the Institute for Women’s Policy Research produces measures of the status of women. Using these measures, researchers at Harvard University showed that women’s status was linked to state-level income inequality.

36

Three of the measures are: women’s political participation, women’s employment and earnings, and women’s social and economic autonomy. When we combine these measures for each US state and relate them to state levels of income inequality, we also find that women’s status is significantly worse in more unequal states, although this is not a particularly strong relationship (Figure 4.4). The fairly wide scatter of points around the line on the graph shows that factors besides inequality affect women’s status. Nevertheless, there is a tendency that cannot be put down to chance, for fewer women to vote or hold political office, for women to earn less, and fewer women to complete college degrees in more unequal states.

Figure 4.4

Women’s status and inequality in US states.

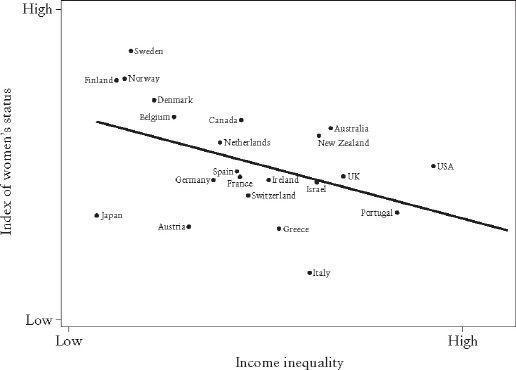

Internationally we find the same thing, and we show this relationship in Figure 4.5. Combining measures of the percentage of women in the legislature, the male–female income gap, and the percentage of women completing higher education to make an index of women’s status, we find that more equal countries do significantly better.

Japan is conspicuous among the most equal countries in that women’s status is lower than we would expect given its level of inequality; Italy also has worse women’s status than expected, and Sweden does better. As with the scattering of points on the American graph above, this shows that other factors are also influencing

Figure 4.5

Women’s status and inequality in rich countries.

women’s status. In both Japan and Italy women have traditionally had lower status than men, whereas Sweden has a long tradition of women’s rights and empowerment. But again, the link between income inequality and women’s status cannot be explained by chance alone, and there is a tendency for women’s status to be better in more equal countries.

Epidemiologists have found that in US states where women’s status is higher, both men and women have lower death rates,

36

and women’s status seems to matter for all women, whether rich or poor.

37

TRUST BEYOND BORDERS

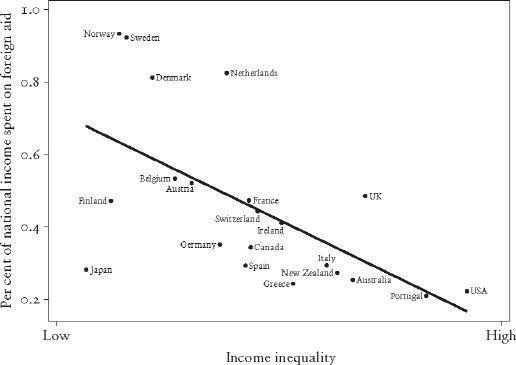

Not surprisingly, just as individuals who trust other people are more likely to give to charity, more equal countries are also more generous to poorer countries. The United Nations’ target for spending on foreign development aid is 0.7 per cent of Gross National Income.

Figure 4.6

Spending on foreign aid and inequality in rich countries.