The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger (12 page)

Read The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger Online

Authors: Richard Wilkinson,Kate Pickett

Tags: #Social Science, #Economics, #General, #Economic Conditions, #Political Science, #Business & Economics

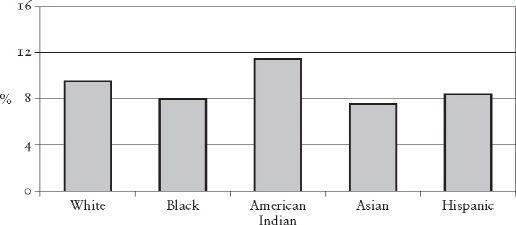

Figure 5.2

US adults reporting frequent mental distress, 1993–2001.

M

53

CLINGING TO THE LADDER

So why do more people tend to have mental health problems in more unequal places? Psychologist and journalist Oliver James uses an analogy with infectious disease to explain the link. The ‘affluenza’ virus, according to James, is a ‘set of values which increase our vulnerability to emotional distress’, which he believes is more common in affluent societies.

54

It entails placing a high value on acquiring money and possessions, looking good in the eyes of others and wanting to be famous. These kinds of values place us at greater risk of depression, anxiety, substance abuse and personality disorder, and are closely related to those we discussed in Chapter 3. In another recent book on the same subject, philosopher Alain de Botton describes ‘status anxiety’ as ‘a worry so pernicious as to be capable of ruining extended stretches of our lives’. When we fail to maintain our position in the social hierarchy we are ‘condemned to consider the successful with bitterness and ourselves with shame’.

55

Economist Robert Frank observes the same phenomenon and calls it ‘luxury fever’.

56

As inequality grows and the super-rich at the top spend more and more on luxury goods, the desire for such things cascades down the income scale and the rest of us struggle to compete and keep up. Advertisers play on this, making us dissatisfied with what we have, and encouraging invidious social comparisons. Another economist, Richard Layard, describes our ‘addiction to income’ – the more we have, the more we feel we need and the more time we spend on striving for material wealth and possessions, at the expense of our family life, relationships, and quality of life.

3

Given the importance of social relationships for mental health, it is not surprising that societies with low levels of trust and weaker community life are also those with worse mental health.

INEQUALITY AND ILLEGAL DRUGS

Low position in the social status hierarchy is painful to most people, so it comes as no surprise to find out that the use of illegal drugs, such as cocaine, marijuana and heroin, is more common in more unequal societies.

Internationally, the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime publishes a

World Drug Report

,

57

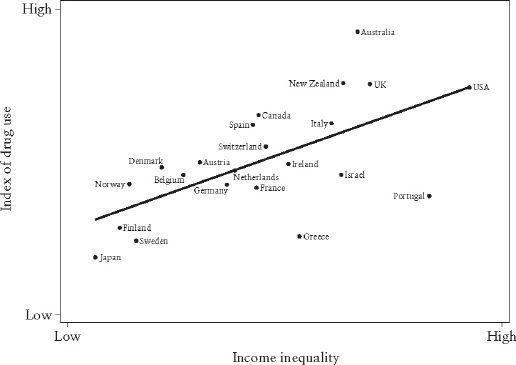

which contains separate data on the use of opiates (such as heroin), cocaine, cannabis, ecstasy and amphetamines. We combined these data to form a single index, giving each drug category the same weight so that the figures were not dominated by the use of any one drug. We use this index in Figure 5.3, which shows a strong tendency for drug use to be more common in more unequal countries.

Within the United States, there is also a tendency for addiction to illegal drugs and deaths from drug overdose to be higher in more unequal states.

58

Figure 5.3

The use of illegal drugs is more common in more unequal countries.

MONKEY BUSINESS

The importance of social status to our mental wellbeing is reflected in the chemical behaviour of our brains. Serotonin and dopamine are among the chemicals that play important roles in the regulation of mood: in humans, low levels of dopamine and serotonin have been linked to depression and other mental disorders. Although we must be cautious in extrapolating to humans, studies in animals show that low social status affects levels of, and responses to, different chemicals in the brain.

In a clever experiment, researchers at Wake Forest School of Medicine in North Carolina took twenty macaque monkeys and housed them for a while in individual cages.

59

They next housed the animals in groups of four and observed the social hierarchies which developed in each group, noting which animals were dominant and which subordinate. They scanned the monkey’s brains before and after they were put into groups. Next, they taught the monkeys that they could administer cocaine to themselves by pressing a lever – they could take as much or as little as they liked.

The results of this experiment were remarkable. Monkeys that had become dominant had more dopamine activity in their brains than they had exhibited before becoming dominant, while monkeys that became subordinate when housed in groups showed no changes in their brain chemistry. The dominant monkeys took much less cocaine than the subordinate monkeys. In effect, the subordinate monkeys were medicating themselves against the impact of their low social status. This kind of experimental evidence in monkeys adds plausibility to our inference that inequality is causally related to mental illness.

At the beginning of this chapter we mentioned the huge number of prescriptions written for mood-altering drugs in the UK and USA; add these to the self-medicating users of illegal drugs and we see the pain wrought by inequality on a very large scale.

Physical health and life expectancy

A sad soul can kill you quicker than a germ.

John Steinbeck,

Travels with Charley

MATERIAL AND PSYCHOSOCIAL DETERMINANTS OF HEALTH

As societies have become richer and our circumstances have changed, so the diseases we suffer from and the most important causes of health and illness have changed.

The history of public health is one of shifting ideas about the causes of disease.

60

–

61

In the nineteenth century, reformers began to collect statistics which showed the burden of ill-health and premature death suffered by the poor living in city slums. This led to the great reforms of the Sanitary Movement. Drainage and sewage systems, rubbish collection, public baths and decent housing, safer working conditions and improvements in food hygiene – all brought major improvements in population health, and life expectancy lengthened as people’s material standards of living advanced.

As we described in Chapter 1, when infectious diseases lost their hold as the major causes of death, the industrialized world underwent a shift, known as the ‘epidemiological transition’, and chronic diseases, such as heart disease and cancer, replaced infections as the major causes of death and poor health. During the greater part of the twentieth century, the predominant approach to improving the health of populations was through ‘lifestyle choices’ and ‘risk factors’ to prevent these chronic conditions. Smoking, high-fat diets, exercise and alcohol were the focus of attention.

But in the latter part of the twentieth century, researchers began to make some surprising discoveries about the determinants of health. They had started to believe that stress was a cause of chronic disease, particularly heart disease. Heart disease was then thought of as the executive’s disease, caused by the excess stress experienced by businessmen in responsible positions. The Whitehall I Study, a long-term follow-up study of male civil servants, was set up in 1967 to investigate the causes of heart disease and other chronic illnesses. Researchers expected to find the highest risk of heart disease among men in the highest status jobs; instead, they found a strong inverse association between position in the civil service hierarchy and death rates. Men in the lowest grade (messengers, doorkeepers, etc.) had a death rate three times higher than that of men in the highest grade (administrators).

62

–

63

Further studies in Whitehall I, and a later study of civil servants, Whitehall II, which included women, have shown that low job status is not only related to a higher risk of heart disease: it is also related to some cancers, chronic lung disease, gastrointestinal disease, depression, suicide, sickness absence from work, back pain and self-reported health.

64

–

66

So was it low status itself that was causing worse health, or could these relationships be explained by differences in lifestyle between civil servants in different grades?

Those in lower grades were indeed more likely to be obese, to smoke, to have higher blood pressure and to be less physically active, but these risk factors explained only one-third of their increased risk of deaths from heart disease.

67

And of course factors such as absolute poverty and unemployment cannot explain the findings, because everybody in these studies was in paid employment. Of all the factors that the Whitehall researchers have studied over the years, job stress and people’s sense of control over their work seem to make the most difference. There are now numerous studies that show the same thing, in different societies and for most kinds of ill-health – low social status has a clear impact on physical health, and not just for people at the very bottom of the social hierarchy. As well as highlighting the importance of social status, this is the other important message from the Whitehall studies. There is a social gradient in health running right across society, and where we are placed in relation to other people matters; those above us have better health, those below us have worse health, from the very bottom to the very top.

68

Understanding these health gradients means understanding why senior administrators live longer than those in professional and executive grades, as well as understanding the worse health profiles of the poor.

Besides our sense of control over our lives, other factors which make a difference to our physical health include our happiness, whether we’re optimistic or pessimistic, and whether we feel hostile or aggressive towards other people. Our psychological wellbeing has a direct impact on our health, and we’re less likely to feel in control, happy, optimistic, etc. if our social status is low.

It’s not just our social status and psychological wellbeing that affects our health. The relationships we have with other people matter too. This idea goes back as far as the work on suicide by Émile Durkheim, one of the founding fathers of sociology, in the late nineteenth century.

69

Durkheim showed that the suicide rates of different countries and populations were related to how well people were integrated into society and whether or not societies were undergoing rapid change and turmoil. But it wasn’t until the 1970s that epidemiologists began to investigate systematically how people’s social networks relate to health, showing that people with fewer friends were at higher risk of death. Having friends, being married, belonging to a religious group or other association and having people who will provide support, are all protective of health.

70

–

71