The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger (27 page)

Read The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger Online

Authors: Richard Wilkinson,Kate Pickett

Tags: #Social Science, #Economics, #General, #Economic Conditions, #Political Science, #Business & Economics

This leads us to another important point: greater equality can be gained either by using taxes and benefits to redistribute very unequal incomes or by greater equality in gross incomes before taxes and benefits, which leaves less need for redistribution. So big government may not always be necessary to gain the advantages of a more equal society. The same applies to other areas of government expenditure. For countries in our international analysis, we collected OECD figures on public social expenditure as a proportion of Gross Domestic Product and found it entirely unrelated to our Index of Health and Social Problems. Perhaps rather counter-intuitively, it also made no difference to the association between inequality and the Index. Part of the reason for this is that governments may spend either to prevent social problems or, where income differences have widened, to deal with the consequences.

Examples of these contrasting routes to greater equality which we have seen in the international data can also be found among the fifty states of the USA. Although the states which perform well are dominated by ones which have more generous welfare provisions, the state which performs best is New Hampshire, which has among the lowest public social expenditure of any state. Like Japan, it appears to get its high degree of equality through an unusual equality of market incomes. Research using data for US states which tried to see whether better welfare services explained the better performance of more equal states found that although – in the US setting – services appear to make a difference, they do not account fully for why more equal states do so much better.

309

The really important implication is that how a society becomes more equal is less important than whether or not it actually does so.

ETHNICITY AND INEQUALITY

People sometimes wonder whether ethnic divisions in societies account for the relationship between inequality and the higher frequency of health and social problems. There are two reasons for thinking that there might be a link. First is the idea that some ethnic groups are inherently less capable and more likely to have problems. This must be rejected because it is simply an expression of racial prejudice. The other, more serious, possibility is that minorities often do worse because they are excluded from the educational and job opportunities needed to do well. In this view, prejudice against minorities might cause ethnic divisions to be associated with bigger income differences and, flowing from this, also with worse health and more frequent social problems. This would, however, produce a relation between income inequality and worse scores on our index through very much the same processes as are responsible for the relationship wherever it occurs. Ethnic divisions may increase social exclusion and discrimination, but ill-health and social problems become more common the greater the relative deprivation people experience – whatever their ethnicity.

People nearer the bottom of society almost always face downward discrimination and prejudice. There are of course important differences between what is seen as class prejudice in societies without ethnic divisions, and as racial prejudice where there are. Although the cultural marks of class are derived inherently from status differentiation, they are less indelible than differences in skin colour. But when differences in ethnicity, religion or language come to be seen as markers of low social status and attract various downward prejudices, social divisions and discrimination may increase.

In the USA, state income inequality is closely related to the proportion of African-Americans in the state’s population. The states with wider income differences tend to be those with larger African-American populations. The same states also have worse outcomes – for instance for health – among both the black

and

the white population. The ethnic divide increases prejudice and so widens income differences. The result is that both communities suffer. Rather than whites enjoying greater privileges resulting from a larger and less well-paid black community, the consequence is that life expectancy is shorter among both black and white populations.

So the answer to the question as to whether what appear to be the effects of inequality may actually be the result of ethnic divisions is that the two involve most of the same processes and should not be seen as alternative explanations. The prejudice which often attaches to ethnic divisions may increase inequality and its effects. Where ethnic differences have become strongly associated with social status divisions, ethnic divisions may provide almost as good an indicator of the scale of social status differentiation as income inequality. In this situation it has been claimed that income differences are trumped, statistically speaking, by ethnic differences in the USA.

310

However, other papers examining this claim have rejected it.

311

–

313

The USA, with its ethnic divisions, is only one of a great many contexts in which the impact of income inequality has been tested. We reviewed 168 published reports of research examining the effect of inequality on health, and there are now around 200 in all.

10

In many of these (for example Portugal) there is no possibility that effects could be attributed to ethnic divisions. An international study which included a measure of each country’s ethnic mix, found that it did not account for the tendency for more unequal societies to be less healthy.

314

DIFFERENT HISTORIES

Another explanation sometimes suggested for why income inequality is related to health and social problems is that what matters is not the inequality itself, but the historical factors which led societies to become more or less equal in the first place – as if inequality stood, almost as a statistical monument, to a history of division. This is most often suggested in relation to the USA when people notice that the more unequal states are usually (but not always) the southern states of the Confederacy with their histories of plantation economies dependent on slave labour. However, the degree of equality or inequality in every setting has its own particular history. If we look to see how Sweden became more equal, or how Britain and a number of other countries have recently become much less so, or how the regions of Russia or China developed varying amounts of equality or inequality, we get different stories in every case. And of course these different backgrounds are important: there is no doubt that there are, in each case, specific historical explanations of why some countries, states or regions are now more or less unequal than others. But the prevalence of ill-health and of social problems in those societies is not simply a patternless reflection of so many unique histories. It is instead patterned according to the amount of inequality which has resulted from those unique histories. What seems to matter therefore is not

how

societies got to where they are now, but

where

– in terms of their level of inequality – it is that they have now got to.

That does not mean that these relations with inequality are set in stone for all time. What does change things is the stage of economic development a society has reached. In this book our focus is exclusively on the rich developed societies. But it is clear that a number of outcomes, including health and violence, are also related to inequality in less developed countries. What happens during the course of economic development is that some problems reverse their social gradients and this changes their associations with inequality. In poorer societies both obesity and heart disease are more common among the rich, but as societies get richer they tend to reverse their social distribution and become more common among the poor. As a result, we find that among poorer countries it is the more unequal ones which have more underweight people – the opposite of the pattern among the rich countries shown in Chapter 7. The age of menarche also changes its social distribution during the course of economic development. When more of the poor were undernourished they reached sexual maturity later than girls in richer families. With the rise in living standards that pattern too has reversed – perhaps contributing to the gradient in teenage pregnancies described in Chapter 9. All in all, it looks as if economic growth and social status differences are the most powerful determinants of many aspects of our lives.

EVERYONE BENEFITS

A common response to research findings in the social sciences is for people to say they are obvious, and then perhaps to add a little scornfully, that there was no need to do all that expensive work to tell us what we already knew. Very often, however, that sense of knowing only seeps in with the benefit of hindsight, after research results have been made known. Try asking people to predict the results in advance and it is clear that all sorts of different things can seem perfectly plausible. Having looked at the evidence in the preceding chapters of how inequality is related to the prevalence of so many problems, we hope that most readers will feel the picture makes immediate intuitive sense. Indeed, it may seem obvious that problems associated with relative deprivation should be more common in more unequal societies. However, if you ask people why greater equality reduces these problems, much the most common guess is that it must be because more equal societies have fewer poor people. The assumption is that greater equality helps those at the bottom. As well as being only a minor part of the proper explanation, it is an assumption which reflects our failure to recognize very important processes affecting our lives and the societies we are part of. The truth is that the vast majority of the population is harmed by greater inequality.

One of the clues, and one which we initially found surprising, is just how big the differences between societies are in the rates of the various problems discussed in Chapters 4–12. Across

whole

populations, rates of mental illness are five times higher in the most unequal compared to the least unequal societies. Similarly, in more unequal societies people are five times as likely to be imprisoned, six times as likely to be clinically obese, and murder rates may be many times higher. The reason why these differences are so big is, quite simply, because the effects of inequality are not confined just to the least well-off: instead they affect the vast majority of the population. To take an example, the reason why life expectancy is 4.5 years shorter for the average American than it is for the average Japanese, is not primarily because the poorest 10 per cent of Americans suffer a life expectancy deficit ten times as large (i.e., forty-five years) while the rest of the population does as well as the Japanese. As epidemiologist Michael Marmot frequently points out, you could take away all the health problems of the poor and still leave most of the problem of health inequalities untouched. Or, to look at it another way, even if you take the death rates just of white Americans, they still do worse – as we shall see in a moment – than the populations of most other developed countries.

Comparisons of health in different groups of the population in more and less equal societies show that the benefits of greater equality are very widespread. Most recently, a study in the

Journal of the American Medical Association

compared health among middle-aged men in the USA and England (not the whole UK).

315

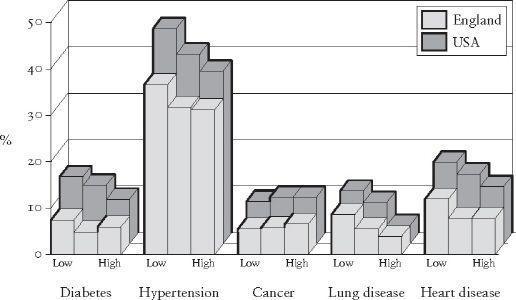

To increase comparability the study was confined to the non-Hispanic white populations in both countries. People were divided into both income and educational categories. In Figure 13.2 rates of diabetes, hypertension, cancer, lung disease and heart disease are shown in each of three educational categories – high, medium and low. The American rates are the darker bars in the background and those for England are the lighter ones in front. There is a consistent tendency for rates of these conditions to be higher in the US than in England, not just among the less well-educated, but across all educational levels. The same was also true of death rates and various biological markers such as blood pressure, cholesterol and stress measures.

Though this is only just apparent, the authors of the study say that the social class differences in health tend to be steeper in the USA than in England regardless of whether people are classified by income or education.

316

Figure 13.2

Rates of illness are lower at both low and high educational levels in England compared to the USA.

315

In that comparison, England was the more equal and the healtheir of the two countries. But there have also been similar comparisons of death rates in Sweden with those in England and Wales. To allow accurate comparisons, Swedish researchers classified a large number of Swedish deaths according to the British occupational class classification. The classification runs from unskilled manual occupations in class V at the bottom, to professional occupations in class I at the top. Figure 13.3 shows the differences they found in death rates for working-age men.

317

Sweden, as the more equal of the two countries, had lower death rates in all occupational classes; so much so that their highest death rates – in the lowest classes – are lower than the highest class in England and Wales.