The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger (26 page)

Read The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger Online

Authors: Richard Wilkinson,Kate Pickett

Tags: #Social Science, #Economics, #General, #Economic Conditions, #Political Science, #Business & Economics

In his book,

The Hot House

, which describes life inside a high-security prison in the US, Pete Earley tells a story about a man in prison with a life sentence for murder.

296

, pp. 74–5

Bowles had been incarcerated for the first time at the age of 15 when he was sent to a juvenile reformatory. The day he arrived, an older, bigger boy came up to him:

‘Hey, what size shoes do you wear?’ the boy asked.

‘Don’t know’ said Bowles ‘Let me see one of ’em will ya?’ the boy asked politely.

Bowles sat down on the floor and removed a shoe. The older boy took off one of his own shoes and put on Bowles’s.

‘How ’bout letting me see the other one?’

‘I took off my other shoe and handed it to him,’ Bowles remembered, ‘and he puts it on and ties it and then walks over to this table and every boy in the place starts laughing at me.

That’s when I realized I am the butt of the joke.’

Bowles grabbed a pool cue and attacked the boy, for which he received a week of hard labour. When a new boy arrived at the reformatory the following week, ‘he too was confronted by a boy who demanded his shoes. Only this time it was Bowles who was taking advantage of the new kid. “It was my turn to dish it out,” he recalled. “I had earned that right.”’

In the same book, Earley tells almost exactly the same story again, only this time he describes a man’s reaction to being sexually assaulted and sodomized on his first night in a county jail at the age of 16. Six years later, arrested in another town, he is put in a jail cell with a ‘kid, probably seventeen or so, and you know what I did? I fucked him.’

296

, pp. 430–31

Displaced aggression among non-human primates has been labelled ‘the bicycling reaction’. Primatologist Volker Summer explains that the image being conjured up is of someone on a racing bicycle, bowing to their superiors, while kicking down on those beneath. He was describing how animals living in strict social hierarchies appease dominant animals and attack inferior ones. Psychologists Jim Sidanius and Felicia Pratto have suggested that human group conflict and oppression, such as racism and sexism, stem from the way in which inequality gives rise to individual and institutional discrimination and the degree to which people are complicit or resistant to some social groups being dominant over others.

297

In more unequal societies, more people are oriented towards dominance; in more egalitarian societies, more people are oriented towards inclusiveness and empathy.

Our final piece of evidence that income inequality causes lower social mobility comes from research which helps to explain why stigmatized groups of people living in more unequal societies can feel more comfortable when separated from the people who look down on them. In a powerful illustration of how discrimination and prejudice damage people’s wellbeing, research shows that the health of ethnic minority groups who live in areas with more people like themselves is sometimes better than that of their more affluent counterparts who live in areas with more of the dominant ethnic group.

298

This is called a ‘group density’ effect, and was first shown in relation to mental illness. Studies in London, for example, have shown a higher incidence of schizophrenia among ethnic minorities living in neighbourhoods with fewer people like themselves,

299

and the same has been shown for suicide

300

and self-harm.

301

More recently, studies in the United States have demonstrated the same effects for heart disease

302

–

303

and low birthweight.

304

–

308

Generally, living in a poorer area is associated with worse health. Members of ethnic minorities who live in areas where there are few like themselves tend to be more affluent, and to live in better neighbourhoods, than those who live in areas with a higher concentration. So to find that these more ethnically isolated individuals are sometimes less healthy is surprising. The probable explanation is that, through the eyes of the majority community, they become more aware of belonging to a low-status minority group and perhaps encounter more frequent prejudice and discrimination and have less support. That the psychological effects of stigma are sometimes strong enough to override the health benefits of material advantage tells us a lot about the power of inequality and brings us back to the importance of social status, social support and friendship, and the influence of social anxiety and stigma discussed in Chapter 3.

Bigger income differences seem to solidify the social structure and decrease the chances of upward mobility. Where there are greater inequalities of outcome, equal opportunity is a significantly more distant prospect.

No man is an Island, entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main.

John Donne,

Meditation XVII

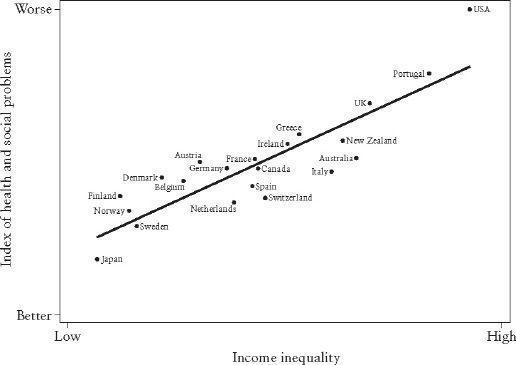

The last nine chapters have shown, among the rich developed countries and among the fifty states of the United States, that most of the important health and social problems of the rich world are more common in more unequal societies. In both settings the relationships are too strong to be dismissed as chance findings. The importance of these relationships can scarcely be overestimated. First, the differences between more and less equal societies are large – problems are anything from three times to ten times as common in the more unequal societies. Second, these differences are not differences between high- and low-risk groups within populations which might apply only to a small proportion of the population, or just to the poor. Rather, they are differences between the prevalence of different problems which apply to whole populations.

DYSFUNCTIONAL SOCIETIES

One of the points which emerge from Chapters 4–12 is a tendency for some countries to do well on just about everything and others to do badly. You can predict a country’s performance on one outcome from a knowledge of others. If – for instance – a country does badly on health, you can predict with some confidence that it will also imprison a larger proportion of its population, have more teenage pregnancies, lower literacy scores, more obesity, worse mental health, and so on. Inequality seems to make countries socially dysfunctional across a wide range of outcomes.

Internationally, at the healthy end of the distribution we always seem to find the Scandinavian countries and Japan. At the opposite end, suffering high rates of most of the health and social problems, are usually the USA, Portugal and the UK. The same is true among the fifty states of the USA. Among those that tend to perform well across the board are New Hampshire, Minnesota, North Dakota and Vermont, and among those which do least well are Mississippi, Louisiana and Alabama.

Figure 13.1 summarizes our findings. It is an exact copy of Figure 2.2. It shows again the relationship between inequality and our combined Index of Health and Social Problems. This graph also shows that the relationship is not dependent on any particular group of countries – for instance those at either end of the distribution.

Figure 13.1

Health and social problems are more common in more unequal countries.

Instead it is robust across the range of inequality found in the developed market democracies. Even though we sometimes find less strong relationships among our analyses of the fifty US states, in the international analyses the USA as a whole is just where its inequality would lead us to expect.

Though some countries’ figures are presumably more accurate than others, it is clearly important that we do not cherry-pick the data. That is why we have used the same set of inequality data, published by the United Nations, throughout. In the analyses of the American states we have used the US census data as published.

However, even if someone had a strong objection to the figures for one or other society, it would clearly not change the overall picture presented in Figure 13.1. The same applies to the figures we use for all the health and social problems. Each set is as provided at source – we take them as published with no ifs or buts.

The only social problem we have encountered which tends to be more common in more equal countries (but not significantly among more equal states in the USA) is, perhaps surprisingly, suicide. The reasons for this are twofold. First, in some countries suicide is not more common lower down the social scale. In Britain a well-defined social gradient has only emerged in recent decades. Second, suicide is often inversely related to homicide. There seems to be something in the psychological cliché that anger sometimes goes in and sometimes goes out: do you blame yourself or others for things that go wrong? In Chapter 3 we noted the rise in the tendency to blame the outside world – defensive narcissism – and the contrasts between the US and Japan. It is notable that in a paper on health in Harlem in New York, suicide was the only cause of death which was less common there than in the rest of the USA.

80

OTHER EXPLANATIONS?

It is clear that there is something which affects how well or badly societies do across a wide range of social problems, but how sure can we be that it is inequality? Before discussing whether inequality plays a causal role, let us first see whether there might be any quite different explanations.

Although people have occasionally suggested that it is the English-speaking countries which do badly, that doesn’t explain much of the evidence. For example, take mental health, where the worst performers among the countries for which there is comparable data are English-speaking. In Chapter 5 we showed that the highest rates are in the USA, followed in turn by Australia, UK, New Zealand and Canada. But even among those countries there is a very strong correlation between the prevalence of mental illness and inequality. So inequality explains why English-speaking countries do badly,

and

it explains which ones do better or worse than others.

Nor is it just the USA and Britain, two countries which do have a lot in common, which do badly on most outcomes. Portugal also does badly. Its poor performance is consistent with its high levels of inequality, but Portugal and the USA could hardly be less alike in other respects.

At the other end of the distribution, it is true that the countries which do well are dominated by the Scandinavian countries, but the country which does best of all is Japan, and Japan is, in other respects, as different as it could be from Sweden, which is the next best performer. Think of the contrasting family structures and the position of women in Japan and Sweden. In both cases these two countries come at opposite ends of the spectrum. Sweden has a very high proportion of births outside marriage and women are almost equally represented in politics. In Japan the opposite is true. There is a similar stark contrast between the proportion of women in paid employment in the two countries. Even how they get their greater equality is quite different. Sweden does it through redistributive taxes and benefits and a large welfare state. As a proportion of national income, public social expenditure in Japan is, in contrast to Sweden, among the lowest of the major developed countries. Japan gets its high degree of equality not so much from redistribution as from a greater equality of market incomes, of earnings

before

taxes and benefits. Yet despite the differences, both countries do well – as their narrow income differences, but almost nothing else, would lead us to expect.