The Sorcerer's Companion: A Guide to the Magical World of Harry Potter (48 page)

Read The Sorcerer's Companion: A Guide to the Magical World of Harry Potter Online

Authors: Allan Zola Kronzek,Elizabeth Kronzek

These ideas soon made their way north, where they found a vocal proponent in a brilliant young German scholar named Cornelius Agrippa. Although Agrippa is now familiar as Ron Weasley’s missing Chocolate Frogs card, he was best known in his own time as the author of the three-volume

Occult Philosophy

, published in 1533. There he argued that all of nature—people, plants, animals, rocks, and minerals—contained hidden properties and powers that could be discovered and put to use. The task of the scholar magician, according to Agrippa, was to apply the tools of magic—divination,

arithmancy

, astrology, the study of

demons

and angels—to uncover the hidden connections and forces in nature and use them to solve problems and cure disease. In the process, Agrippa claimed, man could also discover that part of himself which was linked to the universe at large, and by the force of his own imagination and will, could attain supernatural powers.

Although, to the disappointment of his readers, Agrippa did not explain exactly

how

a magician could achieve his potential, this did not stop many people from trying. Among Agrippa’s many devotees were college students who tried to raise demons in their dorm rooms, physicians who tried to harness the hidden forces of nature to cure their patients, and men of science with a yearning to unravel all the mysteries of the universe. The most famous of these was the English mathematician, astronomer, and astrologer John Dee, who gained a reputation as a magician early in his career and was even imprisoned in 1553 on a charge of attempting to murder Queen Mary by enchantment. Dee believed that he could learn many of the world’s secrets from angels and spirits, whom he tried to contact by gazing into a crystal ball and a magic mirror. Although he rarely got any response from the spirit world himself, Dee had a series of partners who claimed to be able to see and hear the angels. Despite decades of trying, however, no one was ever able to convince these beings to reveal the secrets of God and the universe Dee sought so earnestly to discover.

Nonetheless, by the time of Dee’s death in 1608, interest in magic was quite fashionable among English intellectuals. Throughout much of the seventeenth century, public debates were held at Oxford University on such topics as the power of incantations, the use of magic to cure disease, and the effectiveness of love potions. No doubt many an ambitious young scholar also fancied himself a magician.

Tricksters though they are, theatrical magicians may be the “realest” magicians of all. Storytellers create magic that goes from their imaginations to ours (a great trick in itself); performance magicians take the same impossible feats described in fiction and show them to us—live and in person. Like their legendary counterparts, stage magicians appear and disappear; levitate or fly; predict the future; walk through walls; create something from nothing; and change men into beasts, or ladies into leopards. Performance magicians also cast spells over their audiences, causing them to see things that aren’t there, and not see things that are. It’s no wonder, then, that centuries ago, audiences at magic shows often felt as if they had been bewitched!

This drawing from a German astrology book of 1404 includes the earliest known depiction of a street magician at work. His trick is the classic “Cups and Balls.” Overhead are five of the twelve signs of the zodiac: Taurus the Bull, Leo the Lion, Cancer the Crab, Aries the Ram, and Capricorn the Goat

. (

photo credit 50.4

)

Although performance magic—the art of creating and presenting mystifying illusions—can be found in cultures throughout the world, the first magical entertainers in recorded history are the street conjurers of first- and second-century Greece and Rome. The Latin writers Seneca, Alciphron, and Sextus Empiricus all recorded descriptions of the performers they saw—and particularly of the trick known as “The Cups and Balls,” which is still performed today by modern magicians. Usually done with three small cups and three small balls (no surprise there), this one trick incorporates many of the most startling effects in magic. Under the closest scrutiny of the audience—standing only a foot or two away—the balls vanish into thin air, reappear under the cups, travel impossibly from cup to cup, penetrate the solid tops of the cups, and are sometimes produced from the ears and noses of the spectators. For the grand finale the balls change into something else entirely—pieces of fruit, or sometimes mice or baby chicks!

At first glance this painting from about 1480 simply shows a crowd enjoying a performance of “The Cups and Balls.” But a closer look reveals a pickpocket in the audience. Are the magician and thief partners?

(

photo credit 50.5

)

By necessity, early performers were versatile. Not many tricks had yet been invented, so in addition to performing what we’d describe as “magic tricks” today, performers might also juggle, tumble, put on a puppet show, or exhibit a trained animal such as a dog, monkey, or bear. Schools for street performers existed in Athens, and many performers were renowned for their abilities to astound and amuse even the most sophisticated observers. Greek citizens appreciated skills of all kinds—artistic, athletic, theatrical, musical, and rhetorical—and conjuring was no exception.

As the Roman Empire expanded, magicians began to appear in towns and cities throughout Europe. Some were solo performers, while others joined troupes of acrobats, jugglers, fortune-tellers, poets, and musicians, and traveled from town to town, entertaining royalty in feudal castles and appearing before the common folk in taverns, barns, and courtyards. Surprisingly few details are known about these conjurers, although we do know that many people, especially the clergy, didn’t like them one bit. Though these harmless tricksters were known in England as jugglers and their art was innocently called jugglery, the Church considered conjuring immoral because it was based on deception. The same sleight-of-hand techniques employed in magic tricks could also be used to cheat in gambling, or to swindle the public with “miracle” cures. Others feared and mistrusted conjurers because they suspected a magician’s illusions might rely on supernatural powers. Since the exact nature of a street magician’s methods was usually kept secret, it was easy for those who believed in witchcraft and demons—as many did until the late seventeenth century—to suspect the worst. Furthermore, many performers played on popular magic beliefs by uttering magic words, spinning a magic wand, and pretending to cast spells and call upon supernatural powers.

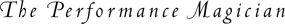

During the eighteenth century, performance magic began to emerge as a form of entertainment in its own right, distinct from juggling, puppetry, and other circus arts. Thanks to new ways of thinking brought by the scientific revolution, conjurers were no longer suspected of having supernatural abilities, and their status as artists of illusion—or “magicians,” as they began to be called during the late 1780s—became clear. Magicians began charging admission to their shows (previously they worked for tips, or sold small items like lucky talismans or medicinal tonics after their shows) and performed more frequently in royal courts. By the mid-1700s, magic shows had made their way to the theatrical stage. Giovanni Giuseppe Pinetti, regarded as one of the first great stage magicians, appeared in Europe’s best theaters during the 1780s and 1790s, performing such feats as removing a man’s shirt without first removing his jacket, apparently reading the mind of a member of the audience, and shooting a nail through chosen card in mid-air, instantly pinning it to the wall.

Giovanni Pinetti was one of the first great theatrical magicians. In one of his most famous feats, a selected card was returned to the deck, the cards were tossed into the air, and the chosen card was pinned to the wall with a nail fired from a pistol

. (

photo credit 50.6

)

Late-nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century magic was characterized by two-hour extravaganzas of illusion, filled with eye-popping wonders. Performers circled the globe with literally tons of apparatus, scenery, and costumes. Harry Houdini, who rose to stardom in vaudeville as a man who could escape from anything—including chains, handcuffs, and prisons—became the most famous and most highly paid entertainer of his time.

Today, people all over the world still stop in their tracks to watch a roving street performer or pay a hefty ticket price to take in a theatrical illusion show. Why? Everybody knows “it’s just a trick.” Are they trying to figure out the secrets? Actually, we think it’s quite the opposite. It’s not the secrets people want; it’s the mysteries. Magic jolts our minds, turns the world upside down and fills us with wonder and astonishment. It also reminds us of something most witches and wizards already know—that the impossible is possible after all.

ost of us take mirrors for granted. We don’t expect them to show us our heart’s deepest desire as the Mirror of Erised does, or to speak to us, like the mirror owned by the evil queen in “Snow White.” We use them for everyday tasks like brushing our teeth and combing our hair and don’t give them a moment’s thought. But the presence of mirrors in our midst has not always been accepted so casually.

ost of us take mirrors for granted. We don’t expect them to show us our heart’s deepest desire as the Mirror of Erised does, or to speak to us, like the mirror owned by the evil queen in “Snow White.” We use them for everyday tasks like brushing our teeth and combing our hair and don’t give them a moment’s thought. But the presence of mirrors in our midst has not always been accepted so casually.