The Sorcerer's Companion: A Guide to the Magical World of Harry Potter (45 page)

Read The Sorcerer's Companion: A Guide to the Magical World of Harry Potter Online

Authors: Allan Zola Kronzek,Elizabeth Kronzek

Ancient magic is often divided into two categories—“high magic” and “low magic”—that can be distinguished primarily by the goals of their practitioners.

High magic, which had much in common with religion, was motivated by the desire to achieve wisdom not available through ordinary experience. When high magicians (who counted among their ranks such notables as the Greek philosopher and mathematician Pythagoras) petitioned gods or spirits, they had the loftiest of goals. They hoped to receive prophetic visions, become healers, achieve insight and self-knowledge, or even become godlike themselves.

Many systems of high magic also taught that every human being was a miniature version of the universe (microcosm), containing within himself all of the elements of the outside world (macrocosm). By developing his inner powers of imagination and intuition, it was believed, the magician would eventually be able to cause real (and seemingly supernatural) changes in the world simply by focusing his emotions, will, and desire. Achieving the powers promised by high magic, however, was the work of a lifetime.

But most people who turned to magic did so with more immediate and practical goals in mind. They wanted to bring luck, riches, fame, political success, health, and beauty; to harm enemies and compel love, to win at sports, know the future, and solve everyday practical problems. The pursuit of these goals is generally known as “low magic”—a category which also includes popular fortune-telling, making potions, casting spells, and the use of

charms

and amulets. From the fourth century

B.C.

onward, hundreds, if not thousands of men and women went into business as professional

sorcerers

and diviners, offering magic for a fee. Although many had a reputation for fraud, historical records show that people of all classes consulted these professional magicians regularly, some openly and some in secret.

In general, magic in the ancient world was more feared than admired. Even those who knew nothing about it believed that they could be harmed or influenced by the magic of someone else. If a politician lost his place in the middle of a speech, or someone unexpectedly became ill, it was not uncommon to assume an enemy’s

curse

was to blame. The sinister reputation of magic was enhanced by its associations with witchcraft in the popular imagination. Greek and Roman literature was filled with highly imaginative and often horrifying descriptions of

witches

and their despicable practices. Erictho, a witch created by the first-century Roman writer Lucan, uses human body parts in her potions, buries her enemies alive, and brings rotting corpses back to life. Although clearly a fictional character (and a memorable one at that), Erictho and witches like her had a strong impact on the popular view of what witchcraft and magic were all about.

Although magic was popular with a public who wanted to be able to consult fortune-tellers and purchase protective charms and amulets, those in positions of authority were wary of astrologers who predicted their deaths and sorcerers who could be hired by their enemies to harm them with curses. In 81

B.C.

the Roman dictator Cornelius Sulla ordered the death penalty for “soothsayers, enchanters, and those who make use of sorcery for evil purposes, those who conjure up demons, who disrupt the elements, [or] who employ waxen images destructively.” A series of similar laws were passed in the following centuries, so that by the fourth century

A.D

., all forms of magic and divination were outlawed in the Roman Empire. At the same time, the Christian Church, which was rapidly growing in power, made a concerted effort to suppress magical practices, which were seen as competition to the Christian faith. All forms of magic were declared to be associated with demons (and thus the Devil) and were prohibited by Church law.

The Church and government continued to work together to oppose magic through the Middle Ages. Nonetheless, magical beliefs and practices, especially those associated with folk medicine (magical healing), were passed on secretly and became part of the repertoire of the “cunning men” or village wizards of later centuries (see

Herbology

,

Magician

).

Beginning around the middle of the twelfth century, magic began to be portrayed in a much more appealing light, at least by writers of fiction. First in France, and later in Germany and England, poets spun marvelous adventure tales that were set in the distant past and involved the magic-filled exploits of valiant knights, beautiful damsels, and heroic kings. These tales, which are now known as the “medieval romances,” downplayed the negative associations of magic with demons and witchcraft. The word “magic” was often avoided, and authors spoke instead of “wonders,” “astonishments,” and “enchantments.” Heroes were provided with swords that furnished superhuman strength, dishes that served themselves, boats and chariots that needed no pilot, and rings that made their wearers invulnerable to fire, drowning, and other catastrophes. Fairies and monsters from mythology also appeared with great regularity, and it was often a fairy who provided the hero with just what he needed to complete the task at hand. Potions, astrological divination, spell casting, and healing herbs were also prominently featured in these epic works. While the idea of “black” magic still lingered, with evil sorcerers and enchantresses appearing from time to time, most of these tales presented magic in a positive light and readers found them as delightful as we do today.

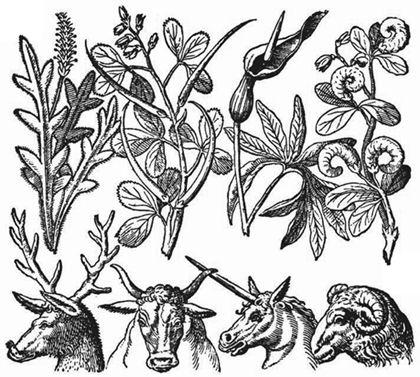

Magic found a new respectability during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, due to the rise of “natural magic,” which did not involve the aid of demons or supernatural beings. A kind of science of its day, natural magic was based on the belief that everything in nature—people, plants, animals, rocks, and minerals—teemed with powerful but hidden forces known as “occult virtues.” Gems, for example, were believed to contain the power to cure disease, affect mood, and even bring good luck. Herbs had occult virtues that could promote healing, sometimes simply by being suspended over a patient’s bed. Even colors and numbers had hidden powers. Furthermore, all of the elements of nature were connected to each other in meaningful but hidden ways. Natural magicians, who included physicians among their ranks, set themselves the challenge of discovering these forces and connections and putting them to use in positive ways.

But being a serious natural magician was no simple task; it required research, study, and careful observation of nature. Sometimes the “occult virtue” of a substance was revealed by its appearance. For example, the herb

scorpius

(named for its resemblance to a scorpion) was deemed an effective remedy for spider bites. Plants and animals with similar shapes were believed to share similar qualities. But especially important to the mastery of natural magic was the study of astrology, since many of the relationships and hidden properties in nature were believed to have emanated directly from the planets and the stars. The gem emerald, the metal copper, and the color green, for example, all shared qualities derived from the planet Venus. Knowing this, the natural magician was able to use these elements in combination when trying to affect those areas of life “ruled” by Venus, such as health, beauty, and love. Using the metal lead, the onyx stone, and the color black was likely to have quite the opposite effect, since they were ruled by Saturn and were associated with death and depression. In addition, the practitioner was required to have extensive knowledge of anatomy and herbology, since curing disease was an important goal of natural magic, and a disease caused by one planetary influence might be cured by an herb regulated by the same planet or, in some cases, its opposite. The natural magician was a kind of wizard of the natural world and a master of combinations—mixing, matching, and exploiting the hidden properties of nature so as to achieve miraculous and beneficial results.

Natural magic taught that plants and animals that looked alike shared the same magical properties

. (

photo credit 49.1

)

Whereas in the ninth or tenth century, a respectable person might have avoided any connection with magic, during the Renaissance natural magic was an appropriate area of study for intellectuals, physicians, clergymen, and anyone with a sense of scientific curiosity. Indeed, scholars of the time might have felt quite at home at Hogwarts, where many elements of natural magic—herbology, astrology,

palmistry, arithmancy

, and the casting of

horoscopes

—are all part of the curriculum.