The Sorcerer's Companion: A Guide to the Magical World of Harry Potter (46 page)

Read The Sorcerer's Companion: A Guide to the Magical World of Harry Potter Online

Authors: Allan Zola Kronzek,Elizabeth Kronzek

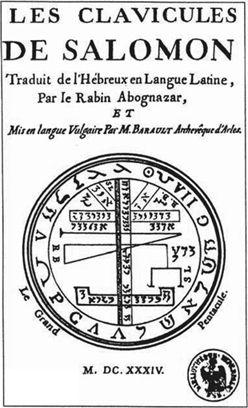

The possibility of raising of spirits, however, was never entirely forgotten. Between the fifteenth and eighteenth centuries, a series of sensational books known as “grimoires” (or Black Books) appeared throughout Europe in many languages. Most were written anonymously, but were attributed to ancient sources (the older a book seemed to be, the more secret wisdom it was thought to contain) including Moses, Aristotle, Noah, Alexander the Great, and most famously, the biblical King Solomon. At first sold and circulated in secret, since owning and using one was a serious crime, these books taught procedures that would supposedly conjure up the spirits and demons of ancient times.

The grimoires promised magic for every imaginable purpose: gaining love, riches, beauty, health, happiness, and celebrity; defeating, cursing, or killing enemies; starting wars, healing the sick, and making the healthy ill, becoming invisible, finding treasure, flying, foretelling the future, and unlocking doors without keys. Not surprisingly, such promises made the books very popular, especially during the seventeenth century, when cheap editions of some grimoires became widely available. From college students to clergymen, devoted believers and the merely curious followed the instructions to see what would happen.

Because they involved elaborate ceremonies and rituals, the procedures taught by the grimoires were known as “ritual magic” or “ceremonial magic.” Essentially, ritual magic followed the same steps used to summon gods and spirits thousands of years earlier. First, the magician drew a large circle on the ground, which he inscribed with magic words, sacred names, and symbols. Then he stepped into the circle (which protected him from the spirits he raised), uttered the incantations that would make the demon appear and grant his wishes, made his demands, and sent the demon on its way. That, at least, was what was supposed to happen.

But before any of this could be attempted, there were weeks, and even months of preparation to be undertaken. According to the many grimoires, all of the apparatus used during the ceremony—candles, perfumes, incense, the sword used to draw the magic circle, the magic wand—had to be brand new. Nor could you simply buy what you needed at Diagon Alley. Ceremonial candles had to be personally molded by the magician using wax made by bees that had never made wax before. The magic wand had to be freshly carved from a hazel branch, hewn from a tree with one blow of a newly made sword. Colored inks used to draw magical talismans had to be freshly prepared and kept in a new inkwell; and, according to one of the best known of all grimoires,

The Key of Solomon

, the quill pen used to draw the talismans had to be fashioned from the third feather of the right wing of a male goose. Moreover, each step had to be carried out according to the principles of astrology, under the influence of the appropriate planets at the right times of year. The magician also had to prepare himself spiritually for the ceremony by special diet, fasting, ritual bathing, and other purifying practices.

A seventeenth-century French edition of

The Key of Solomon,

the best known of all grimoires

. (

photo credit 49.2

)

None of this, of course, was any guarantee that anything would happen during the ceremony. In fact, instructions were so elaborate, so specific, and usually so bizarre that they were virtually impossible to actually carry out as described. It was no wonder, then, that despite repeated pleadings, incantations, and sincerity, spirits routinely failed to appear, except in the imaginations of some practitioners and grimoire writers. Failures, however, were also easily explained. With so many details, somewhere, somehow, something had been overlooked.

A

sixteenth-century ceremonial magician orders a demon to do his bidding. The magic circle was supposed to protect the magician from harm

. (

photo credit 49.3

)

Belief in magic began to decline during the mid-seventeenth century as people began to discover more practical and effective ways to deal with their problems. Modern chemistry led to the creation of new medicines that replaced cures performed by the principles of herbology, astrology, and natural magic. With the rise of scientific thinking, ideas about how the world worked were tested by experiment, and the power of magic words, spells, amulets, and talismans was increasingly called into question.

Today, the idea of obtaining extraordinary powers by conjuring spirits has disappeared from most parts of the modern world. Yet it’s also true that the modern world is more magical than it has ever been. Things once thought to be impossible, like flying or talking to someone halfway across the world, are daily occurrences. The aspirations of natural magic—discovering and harnessing the hidden powers of nature—have been achieved by modern science. And while the principles of astrology have been disproved, it turns out, ironically, that all the occult virtues in nature

did

come from the stars, since we now know that all of the elements of the natural world, including ourselves, originated in the materials of exploding suns. As it was to the ancients, the universe remains an amazing place, filled with wonder, impossible possibilities, and magic.

The adventures of Harry Potter and his friends have been enjoyed in exactly the same way that the medieval romances once were, except by millions more people. Theatrical magic is more popular than at any time in history. Whether in literary or theatrical form, magic confirms our intuition of “another reality.” Although magic may make no sense to our logical minds, it makes perfect sense to our creative and intuitive minds, which operate by a different set of rules. The appeal of magic seems to have nothing to do with whether it’s “real.” Magic came from the imagination and it feeds the imagination. And it seems to us, it always will.

izard. Witch. Sorcerer. Warlock. Enchantress. Conjurer. Charmer. Diviner. These are but a few of the many guises of the magician.

izard. Witch. Sorcerer. Warlock. Enchantress. Conjurer. Charmer. Diviner. These are but a few of the many guises of the magician.

A magician is simply someone who does magic, whether it is “real” magic like that of Albus Dumbledore, or something that simply appears to be magical, like the spell casting of a village

witch

or

wizard

or the great escapes of a stage magician like Harry Houdini.

Almost every culture in the world has told tales of legendary magicians who could soar through the sky, disappear, or produce banquets from thin air. Each culture has also had its real, historical magicians who claimed to have special powers and used a variety of techniques to perform apparently magical acts. Although we cannot do justice to all the world’s magicians, here are some of the basic types:

The purest form of magic is done by the wizards and witches of myth, legend and fairy tales, who can do just about anything they want. They can fly, be in two places at once, disappear and reappear, produce any object desired, change their own shape or the shape of others, converse with animals, animate objects, foretell the future, cure illness, and travel through time. Some legendary magicians have great knowledge of

potions

and

spells

, but often these are unnecessary. Most of the time, a

magic word

and a wave of the wand are all it takes.

Tales of legendary magicians go back thousands of years. In ancient Egypt, where magic rituals were part of everyday culture, imaginative accounts of the powers of great wizards never failed to delight the listener. In one charming tale set in the time of King Cheops (2600

B.C.

) the magician Jajamanekh comes to the aid of a young woman who has dropped her turquoise hair ornament overboard while boating on a lake near the royal palace. With a few magic words, Jajamanekh neatly picks up half of the lake, stacks it on top of the other half, and retrieves the hairpiece for the delighted young lady. In the literature of ancient Greece, where legendary magicians were usually women, the sorceress

Circe

and her niece Medea were able to turn men into beasts, return youth to the aged, and divine the future. The Roman poet Virgil tells of the wizard Moeris, who can move crops from one field to another, transform himself into a

werewolf

, and restore life to the dead.