The Sorcerer's Companion: A Guide to the Magical World of Harry Potter (43 page)

Read The Sorcerer's Companion: A Guide to the Magical World of Harry Potter Online

Authors: Allan Zola Kronzek,Elizabeth Kronzek

Aristotle had his own theory about thought transference. He suggested that thoughts traveled in waves, like the ripples generated when a stone is thrown into a pool of water, and were more likely to get through to someone asleep because “those that are asleep have a greater perception of small inward motions than those that are awake.”

Despite these early speculations, systematic research into mind-to-mind communication did not begin until 1882, when a group of eminent English scientists and scholars founded the Society for Psychical Research (SPR). Their goal was the scientific investigation of every aspect of the paranormal, including

poltergeists

, clairvoyance, mesmerism (hypnotism), mediums, and spirit contact. These topics were of enormous interest to the Victorian public and eagerly followed in the press. Research into telepathy (from the Greek roots

tele

, meaning “distant,” and

pathe

, meaning “feeling”) was divided into two main areas: (1) collecting and categorizing reports from individuals who had experienced “spontaneous telepathy,” that is, received information that arrived in a dream or vision that later turned out to be true; and (2) investigating the claims of self-proclaimed professional “mind readers.”

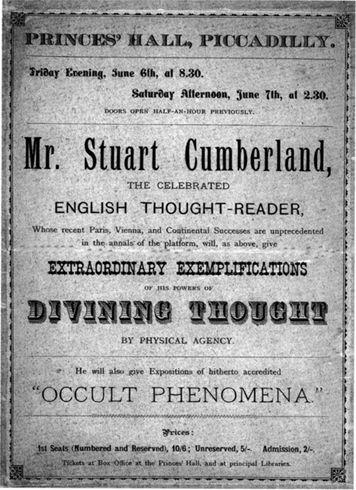

Mind reading as a form of entertainment had been introduced to England from America in 1880 and had become something of a national craze. Professional “thought-readers” appeared to detect the unspoken thoughts of total strangers. One of the most famous, Stuart Cumberland, was known for being able to duplicate a drawing sketched in secret by an audience member and to reveal the serial numbers on a bill known to only one person. The SPR tried to determine if this was genuine telepathy or a clever trick. And if real, how did it work?

Program, June 6–7, 1884

(

photo credit 47.1

)

Definitive answers proved elusive. While many mind readers were exposed as tricksters, members of the SPR also endorsed apparently real psychics and mediums (many of whom who were later exposed as frauds). In the early 1930s, Dr. J. B. Rhine took research in a new direction by putting the emphasis on laboratory experiments. He established the world’s first parapsychological laboratory at Duke University in North Carolina, where he and his colleagues conducted more than 100,000 experiments. The best known of these involved Zener Cards—a set of 25 cards consisting of five different symbols—star, circle, cross, square, and wavy lines—each repeated five times. A researcher would shuffle the cards, and then a “sender” (often a student volunteer) would look at the top card of the deck and try to telepathically transmit it to a “receiver.” Statistically, the receiver has a twenty percent chance of guessing the correct symbol purely by chance, so in order to demonstrate telepathy, the results must be significantly higher than twenty percent.

In 1934, Rhine published his conclusions in

Extra-Sensory Perception

, a book of case studies in which he claimed that certain individuals had scored so far above chance that telepathy was “an actual and demonstrable occurrence,” a scientific fact. However, when researchers at other universities tried repeating the experiments, they came up with no evidence for telepathy. It is now recognized that Rhine’s early experiments were flawed: subjects had the opportunity to cheat, test administers may have given inadvertent clues, and the statistical method was imperfect. More than seventy-five years later, the situation remains pretty much the same. Researchers are still trying to document the telepathy in the laboratory, but the case has yet to be made.

The lack of solid scientific evidence, however, does not rule out the existence of telepathy, nor has it diminished the widespread belief that mind-to-mind communication is a common occurrence. Many well-respected individuals have reported their own experiences. Mark Twain called the phenomenon “mental telegraphy” and believed it was “exceedingly common.” In

Mental Radio

, Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist Upton Sinclair described his wife’s ability to reproduce drawings she had never seen. Telepathy also continues to be a staple of science fiction: the Jedi of the Star Wars saga are telepaths, and the Vulcans and Betazoids of Star Trek practice their own versions of Legilimency.

Some futurists have suggested that the next step is evolutionary. Research is underway to see if minds can link up by interfacing with a computer. Participants would wear brain-scanning devices that would record the electronic patterns made by their thoughts, and a computer would translate the thoughts into language, or perhaps deliver them directly into the mind of a recipient. Others suggest that it is only a matter of time until everyone has access to the telepathic powers they already posses—powers that lie dormant and show themselves only in times of stress, as Democritus observed centuries ago. When that happens, it might be wise to heed Professor Snape’s advice and begin lessons in Occlumency. You just might want to keep some thoughts to yourself.

he Quidditch World Cup may not be filled with gold, but it’s worth a bundle to the Irish and Bulgarian teams as they battle it out at wizardry’s premiere sporting event. When the Irish emerge victorious, they have no complaints about the performance of their exuberant leprechaun cheerleaders. By most accounts, however, encounters between humans and leprechauns are rarely so harmonious.

he Quidditch World Cup may not be filled with gold, but it’s worth a bundle to the Irish and Bulgarian teams as they battle it out at wizardry’s premiere sporting event. When the Irish emerge victorious, they have no complaints about the performance of their exuberant leprechaun cheerleaders. By most accounts, however, encounters between humans and leprechauns are rarely so harmonious.

Although these

fairies

of Irish folklore spend most of their time making shoes, it’s no secret that leprechauns also keep watch over ancient stores of buried gold and other treasure. Legend holds that humans may share in this wealth, but only if they are clever enough to capture a leprechaun and force him to give up his riches in exchange for freedom. This is no easy feat, for these tiny men (all leprechauns are male) are extremely clever and will usually find a way to turn the tables on a human. A typical tale begins with a traveler who tracks down a leprechaun after hearing the faint sound of hammering coming from a secluded forest or meadow. When discovered, the leprechaun usually proves friendly enough until his visitor demands that he reveal the location of his gold. Then he may throw a tantrum, deny he has any gold, point to an imaginary swarm of bees or a tree about to fall, or do anything else he can think of to create a distraction. The instant the human looks away, the leprechaun will vanish. If this trick fails, there are plenty of others. The leprechaun may become surprisingly generous and, with a twinkle in his eye, hand over a weighty purse of gold coins. But as fans of the Quidditch World Cup learned when showered with leprechaun gold, it’s best not to run up debts too soon, for this gift will soon turn to ashes or vanish altogether.

Modern depictions of leprechauns, especially those seen around St. Patrick’s Day, usually show a little man dressed all in green. Traditionally, however, the dapper leprechaun might be seen in a red jacket with shiny silver buttons, blue or brown stockings, big shoes with fat silver buckles, and a high-crowned or three-cornered hat. Standing tall at six inches to two feet, leprechauns can look both mischievous and dignified. Many wear a beard and smoke a pipe. When on the job, a leprechaun often wears a leather cobbler’s apron and carries a little hammer to make or mend a tiny, fairy-size shoe. Apparently, leprechauns don’t treat their fellow fairies much better than humans, for they provide them with only single shoes, never pairs. In fact, some scholars believe the word leprechaun is derived from the Gaelic

leith bhrogan

, meaning “maker of one shoe.” But perhaps the leprechauns’ failure to make pairs is merely an oversight, for they are frequently tipsy from drinking too much home-brewed beer.