The Rise and Fall of Modern Medicine (46 page)

Read The Rise and Fall of Modern Medicine Online

Authors: James Le Fanu

It was at this crucial moment that Keys's thesis emerged, now endorsed (thanks to his efforts) by the American Heart Association and without a serious challenger, to become the central explanation of the coronary epidemic. The epidemic was now so severe that virtually any explanation would have served as a way of making sense of why for over thirty years the toll of young men dying from coronaries had increased exponentially year by year, with absolutely no sign it was coming to an end. Like the AIDS epidemic of the 1980s, coronary disease became an absolute priority for those engaged in promoting the public health. By the early 1970s, the time had come to provide the incontrovertible proof that modifying these risk factors would prevent heart disease. To this end the protagonists in both the United States and Europe launched, in the early 1970s, the largest and most expensive scientific experiment ever conceived in the history of medicine, involving over 60,000 men and costing in excess of £100 million.

In the United States 360,000 middle-aged men were

interviewed to find the 12,000 at highest risk. Most were smokers, had been diagnosed as having raised blood pressure while still young and had markedly elevated cholesterol levels. They were then randomly allocated into either an âintervention' or a âcontrol' group and the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial (MRFIT) was launched. The complexity and expense of this study lay in the need to change people's lives â to encourage them to give up one style of life and adopt another. There was little difficulty in ensuring that those with raised blood pressure were adequately treated, by giving appropriate medication. Discouraging smoking was, as always, more difficult, and every conceivable way was deployed to encourage the men to quit, including monetary rewards, hypnosis and aversion techniques. But such practicalities were nothing when compared to what was required to achieve the dietary modifications necessary to lower the cholesterol level. Nothing other than monumental changes would do, so the participants were showered with nutritional information, taught how to shop for groceries, what to order in restaurants, given advice on how to rewrite their favourite recipes, asked to record everything they ate and sign contracts pledging to abstain from various foods. They were told to eat only low-fat cheese, restricted to two eggs a week and instructed to avoid all cakes, puddings and pastries and to reduce markedly the amount of meat consumed. These prodigious efforts were rewarded â the average amount of saturated fat in their diet fell by about a quarter â but disappointingly their cholesterol level only fell by just over 5 per cent.

The dedication and energy of those involved in MRFIT was admirable, but it would be quite unrealistic to expect that such prodigious efforts would be readily applicable in the real world. Hence the interest in the second of the two studies launched at

the same time and organised by Geoffrey Rose, Professor of Epidemiology at the London School of Hygiene, the leading standard-bearer for Keys's hypothesis in Europe. His project, co-ordinated under the auspices of the World Health Organisation and thus known as the âWHO Trial', was much larger, involving almost 50,000 men in sixty-six factories in Britain, Belgium, Italy and Poland. The workers in the âintervention' group were exposed to a blitzkrieg of health education to encourage them to change their lifestyle, backed up by evening meetings, floor shows, talks about heart disease and cookery demonstrations. Those in the âcontrol' factories were left in peace.

It would seem unlikely on first principles, given that the rise in heart disease could not be explained by increasing amounts of saturated fat in the diet of Western nations, that these radical dietary changes to reduce fat consumption would be effective in preventing it. And so it turned out. Despite the prodigious efforts of the MRFIT trial to cajole so many men into changing their lives and giving up the pleasures of meat and eggs and cakes and pastries and much else besides, the results published in 1982 show they were no less likely to suffer from a heart attack than those in the âcontrol' group.

18

Seven months later the WHO Trial delivered precisely the same verdict.

19

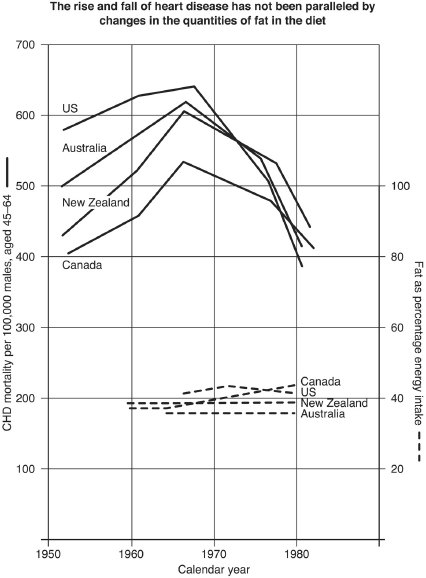

Nor was this the only problem for Keys's thesis. There are only two ways in which it could be tested experimentally. The first, as represented by the trials, was to encourage people to change their diets and see the effect on heart disease. This, as has been noted, did not work. The alternative was to perform the experiment, as it were, the other way round and look to see whether the rising incidence of heart disease over several decades had been paralleled by major changes in what people ate. This, as has already been noted, was a central weakness of

the thesis, as the twenty-fold rise in heart disease throughout the 1940s and 1950s had not been paralleled by increasing amounts of fat in the diet. By the early 1980s it was quite apparent that this original trend had been reversed and that the incidence of heart disease had gone into steep decline.

20

The decline, it must be appreciated, was universal, across all ages, classes and ethnic groups, and international, occurring simultaneously in the United States, Canada, New Zealand and Australia. Thus if the âlifestyle' theory of heart disease were correct, people would have had to have made substantial changes in their diet at least ten years earlier, not just in the United States but in all these other countries as well. Clearly this was impossible for, as shown in the graph on page 375, the precipitous rise and equally precipitous fall in heart disease occurs in different countries in parallel, while the proportion of fat in the diet hardly changes. Indeed, by the early 1980s, when this fall in heart disease was becoming ever more marked, the necessary dietary changes would have had to be monumental, much greater than those imposed on the âintervention' group in the MRFIT trial. Rather, this pattern of âthe rise and fall' of heart disease resembled âthe rise and fall' of an infectious disease. It was not a âsocial' but a âbiological' pattern, with the obvious implication that some unknown biological factor must be the culprit, either by influencing the severity of atheroma in the coronary arteries, or by precipitating the clot that causes the heart attack â or both.

The seriousness of these developments for the proponents of The Social Theory is obvious enough. They were just getting into their stride with their ambitious programme to realign medicine towards preventing the Diseases of Affluence and now suddenly the scientific validity of its central pillar â the implication of the Western diet in the epidemic of heart disease â seemed highly questionable. There were two powerful interested

parties in particular who could not acknowledge defeat. The first were those like Keys, Stamler, Rose and many others who had invested a lifetime's work and hundreds of millions of pounds of research funds in trying to prove the thesis. The second were the drug companies who had made substantial capital investment in the development of cholesterol-lowering drugs, for which, naturally, they needed a market. Now cholesterol, as has been noted, is not entirely innocent, as, whatever might be the unknown âbiological' cause that explained the rise and fall of heart disease, it clearly was most likely to hit those with higher than average cholesterol levels and therefore more severe atheroma in their coronary arteries. Hence both the drug companies and the dietary protagonists had a mutual interest in salvaging Keys's thesis. If the drug companies could show that their powerful cholesterol-lowering drugs reduced the chances of a heart attack in those with markedly raised cholesterol levels (which was probable), this would be evidence that the disease was indeed âpreventable', which would then shore up the position of the proponents of the dietary theory like Stamler and Keys. And if they could, in their turn, convince the public that too much fat caused heart disease, so everyone should lower their cholesterol levels, this would markedly increase the market for cholesterol-lowering drugs way beyond the minority âat high risk'. And that is precisely what happened.

We start with the dietary protagonists. Clearly, for The Social Theory to survive despite the negative results of the trials, the focus would have to be shifted away from the scientific arena, where it could be debated, towards authoritative

ex cathedra

assertions that bacon and eggs (or their equivalent) really did cause heart attacks. The best way of ensuring this âfact management' was through the medium of reports from âexpert committees' made up of the protagonists â the same ploy by which Keys first had his thesis officially endorsed by the American Heart Association back in 1961. From the early 1980s onwards, these expert committees multiplied like rabbits, each claiming to have examined the entrails of the scientific evidence to come to precisely the same verdict, that the Western diet caused heart disease (and strokes, diabetes, breast cancer and much else besides).

The message of these reports was duly picked up by sympathetic journalists who passed it on to the wider public. Thus, in 1985, the readers of

The Times

were informed: âWestern food is the main single underlying cause of Western disease which leaders of the medical profession [describe] in apocalyptic terms as a holocaust, which medicine can do nothing to check.'

This very serious state of affairs naturally raised the important question of why so little was being done about it. Every good story requires a villain and, sure enough, the best intentions of the experts were being thwarted by powerful antagonistic forces in the form of the food industry and farmers â and their apologists, a small group of âcorrupt' scientists. âThere are some who, from a position of authority, assert that fat and salt in the quantities consumed in Britain today are harmless to health. As far as I know they are all employed, paid by or associated with the food industry.' The role of these scientific sceptics in condoning the food industry's attempts to peddle lethal foodstuffs to the public was âthe biggest scandal since the day 150 years ago when officials refused to act on the fact that cholera was caused by open sewers'.

21

As for the second interested party, the pharmaceutical industry, the prospects for the mass prescription of cholesterol-lowering drugs were much enhanced with the publication in 1984 of a clinical trial demonstrating that, for those at âhigh risk',

the drug cholestyramine reduced the chances of dying from a heart attack by 25 per cent. This result, according to the chief organiser, offered âconclusive proof' that heart disease could be prevented. Admittedly the participants had all been at âvery high risk', but âthe trial's implications could and should be extended to all age groups and those with more modest elevations of cholesterol'.

22

The following week

Time

's cover featured a plate of bacon and eggs arranged to resemble a doleful face with the headline âCholesterol: And now the Bad News . . . '. âSorry, it's true, cholesterol really is a killer,' ran the story on the inside page.

Newsweek

pursued the same line, quoting an expert opinion that this was âa milestone, with implications for all Americans'.

And how did the participants in this âlandmark study' fare? Cholestyramine must be sprinkled directly on to food, rendering meals unpalatable, with two-thirds of the participants reporting moderate to serious side-effects of constipation, gas, heartburn and bloating. After seven years of this regime thirty out of the 1,900 taking cholestyramine had had a fatal heart attack compared to thirty-eight out of the similar number in the control group. This indeed can be interpreted as âreducing the chances of dying from a heart attack by 25 per cent' (8 divided by 38 and multiplied by 100 equals almost 25). But put another way, almost 2,000 men had to take cholestyramine for seven years to increase their chances of avoiding a heart attack by less than half of 1 per cent (8 divided by 2,000 multiplied by 100). This seems a modest enough achievement, except that overall cholestyramine made no difference at all, as the total number of deaths in the âintervention' and âcontrol' groups were exactly the same, with the modest reduction in heart disease mortality in those taking cholestyramine being balanced by an increased risk of death âfrom other causes'.

The gold mine of âcholesterol-lowering for all' was much too enticing to be deflected by such considerations. After all, seven years' worth of cholestyramine for 2,000 men added up to £9 million, which worked out at over £1 million for each of the eight fatal heart attacks prevented and (as there was no difference in overall mortality) an infinite sum for every life saved.

Now for âthe sting'. It is only natural to be suspicious when a drug company extols the benefits of drug X, but an entirely different matter when the desirability of taking such a drug is endorsed by apparently âindependent' experts as part of an âeducation' programme. And sure enough, in December 1984, just a few months after the cholestyramine trial (and

Time

's gloss upon it), the US National Institutes of Health launched the National Cholesterol Education Program with the double message: âThe blood cholesterol level of most Americans is undesirably high' and should be reduced because âit has been established beyond reasonable doubt' that this would reduce the subsequent risk of a heart attack.

23