The Rise and Fall of Modern Medicine (44 page)

Read The Rise and Fall of Modern Medicine Online

Authors: James Le Fanu

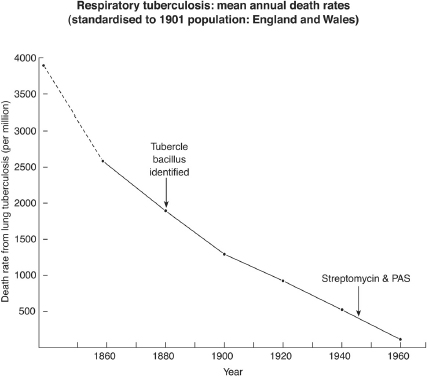

Similar sentiments had been expressed before. If McKeown had merely limited his observations to the past, they would have had little impact, but he used this example of the apparently limited contribution of antibiotics (such as streptomycin) to the decline of tuberculosis to infer that the same principles applied to contemporary medical problems in the 1970s. And certainly the parallel was compelling enough. There were, he claimed, two broad categories of preventable illness: the âDiseases of Poverty', which obviously included infectious diseases like tuberculosis, but also the âDiseases of Affluence' which had become more prevalent with growing prosperity â cancer, strokes and heart disease. So, just as the Diseases of Poverty had declined as society had become wealthier, the Diseases of Affluence would diminish by adopting a more rigorous and ascetic lifestyle: âThe diseases associated with affluence are determined by personal behaviour, for example refined foods became widely available from the early nineteenth century . . . sedentary living dates from the introduction of mechanised transport, cigarette smoking on a significant scale has occurred only in recent decades.'

(Adapted from Thomas McKeown

, The Role of Medicine,

Oxford: Blackwell, 1979.)

The characterisation of these preventable Diseases of Affluence struck a most resonant chord. Thus the following year, in 1977, the Assistant Secretary of Health to the US Government told a Congressional Subcommittee: âThere is general agreement that the kinds and amounts of food we consume may be the major factor associated with the causes of cancer, circulatory disorders (heart disease and strokes) and other chronic disorders.' Soon afterwards Sir Richard Doll, former colleague of Sir Austin Bradford Hill and now Professor of Medicine at Oxford, provided his authoritative support. Following an extensive review of the relevant evidence, he had discovered that, leaving aside smoking, patterns of food consumption accounted for 70 per cent of all cancers in the Western world.

2

And there was more. Professor Samuel Epstein of the University of Illinois, writing in the journal

Nature

in

1980, argued that a further 20 per cent of cancers were caused by minute quantities of chemical pollutants in the air and water and were thus also theoretically preventable.

3

So, within four years of McKeown propounding his Social Theory, it seemed that he had been well and truly vindicated, and if attention were paid to modifying these âsocial factors' then more deaths would be prevented every year than there were people dying.

4

It cannot be sufficiently stressed what a radical departure this Social Theory of disease was from the preceding thirty years. The achievements of the previous three decades had been hard-won; the pursuit of the cure for leukaemia had taken the best part of twenty-five years, drawing on specialist scientific expertise from many disciplines and requiring the accidental discovery of no less than four different types of anti-cancer drugs. But now here were distinguished doctors and scientists arguing that the future of medicine lay in a completely different direction: get people to change their diets, control pollution, and many diseases would evaporate like snow on a sunny day. Could it be that simple? Why had no one conceived of the problems of disease in this way before? Certainly, had they done so, much time and energy would have been saved trying to discover treatments for common diseases that now could so easily be prevented.

It might sound almost too good to be true, but The Social Theory was enthusiastically taken up by many. Politicians and policy-makers, alarmed at the escalating costs of modern medicine, were impressed by McKeown's arguments that the emphasis on expensive hospital-oriented medical services was misdirected and that, were the emphasis to be shifted towards âprevention', the health services would be not only much more effective but also a lot cheaper into the bargain. Such sentiments were echoed by intelligent observers, as reflected in the BBC's

prestigious Reith Lectures for 1980, given by a young lawyer, Ian Kennedy, committed to the âunmasking of medicine'. âThe elimination of the major infections has served as a star witness for the triumphs of modern medicine over illness,' he observed, âbut this has had the unfortunate consequence of creating a “mythology” where the doctor is portrayed as a crusader engaging in holy wars against the enemy of disease . . . The promise of more and more money to wage this war will not improve the quality of health care.' Rather âthe whole project' had to be reoriented towards âprevention and health promotion' â and who could argue with that?

5

Since the war, âthe public health' had been very much the poor relation of medicine, marginalised by the glamorous successes of open-heart surgery and transplanting kidneys. Here now was the opportunity to change all this and reassert the priority of preventive measures in the finest tradition of the nineteenth-century sanitary reformers. This ânew' public health movement, as it styled itself, was to move forward relentlessly from the early 1980s, warning people of the dangers lurking in their food supply and in the air and water. And it was a dynamic process that every year brought evidence of yet further unanticipated hazards of everyday life, while those responsible for health policy felt it necessary to proffer ever more precise advice on how the public should lead their lives.

And how much of it was true? It is necessary to bear a few general points in mind. First, the radicalism of The Social Theory is that, as suggested, it goes far beyond the self-evident truism that those who pursue a âsober lifestyle' â drinking sensibly, abjuring tobacco, avoiding obesity and staying fit â are likely to live longer and healthier lives. Rather, contentiously, it makes specific claims about the causative role of commonly consumed foods and environmental pollution as a major factor in common illnesses. Next, we are citizens of a society in which,

utterly uniquely for the first time in history, most people now live out their natural lifespan to die from diseases strongly determined by ageing. Thus the putative gains from âprevention' (if real) are likely to be quite small. Further, the human organism could not survive if its physiological functions such as blood pressure (implicated in stroke) or level of cholesterol (implicated in heart disease) varied widely in response to changes in the amount and type of food consumed. These functions rather are protected by a â

milieu intérieur

', a multiplicity of different feedback mechanisms that combine to ensure a âsteady state'. Hence truly substantial changes in the pattern of food consumption are required to change them and to influence the types of disease in which they have been implicated.

Finally, man, as the end product of hundreds of millions of years of evolution, is highly successful as a species by virtue of this phenomenal adaptability. Humans can and do live and prosper in a bewildering variety of different habitats, from the plains of Africa to the Arctic wastes. No other species has the same facility, so it might seem improbable that for some reason right at the end of the twentieth century subtle changes in the pattern of food consumption should cause lethal diseases.

Finally, the evidence for The Social Theory is overwhelmingly statistical, based on the inference that the lives we lead and the food we eat cause disease in the same way that smoking causes lung cancer. Throughout this discussion it will be necessary to bear in mind Sir Austin Bradford Hill's insistence that such statistical inferences by themselves have no meaning unless they are internally coherent, that is to say, when the several different types of evidence for an association between an environmental factor and disease (such as tobacco and lung cancer) are examined, they all point to the same conclusion. Put another way, no matter how plausible the link between dietary

fat and heart disease might seem, just one substantial inconsistency in the statistical evidence effectively undermines it.

We now turn to examine The Social Theory in more detail, but not before noting that McKeown's central argument â that medical intervention could not take the credit for the decline in tuberculosis â is much less compelling than it might appear. The bacillus that causes tuberculosis spreads itself around by the simple expedient of irritating the airways of the lungs of those infected, causing them to cough and sneeze. Thus millions of droplets of lung secretions are scattered into the atmosphere every time a patient with tuberculosis coughs, some of which will contain tubercle bacilli which, if inhaled by those nearby, will spread the infection. This dissemination of infection will clearly be interrupted if patients with tuberculosis are isolated in a sanatorium with others similarly infected until they either die, or, as happened to Bradford Hill, are cured by the admittedly crude methods available prior to the introduction of streptomycin. McKeown, it seems, overlooked, presumably deliberately, this important point, for as a historian subsequently observed:

McKeown mis-stated, or failed to understand, the point demonstrated with brilliant clarity in the classic book

The Prevention of Tuberculosis

published in 1908, namely that the effect of placing consumptive patients in poor law infirmaries was to separate them from the general populace and to restrict the spread of the disease â the proportion of consumptive patients thus segregated corresponded closely to the progressive rate of decline of tuberculosis in England and Wales.

Certainly, rising living standards and particularly improvements in housing would have contributed to tuberculosis's

decline, but âmedical intervention' â the identification of those with tuberculosis by examining their sputum and their subsequent incarceration in a sanatorium â was also very important. This might not be a conventional view of âmedical intervention', but it was instigated and co-ordinated by doctors with the clear intention of reducing the spread of the disease, so medical intervention it must be.

6

When the slightest breath of scepticism is sufficient to undermine McKeown's argument, perhaps a similar attitude will prove just as damaging to The Social Theory he instigated. We start with âThe Rise and Fall of Heart Disease', the bitterest intellectual controversy of post-war medicine.

HE

R

ISE AND

F

ALL OF

H

EART

D

ISEASE

The modern epidemic of heart disease started quite suddenly in the 1930s. Doctors had no difficulty in recognising its gravity because so many of their colleagues were among its early victims, apparently healthy middle-aged physicians who, for no obvious reasons, suddenly collapsed and died. Within a decade, heart disease had become much the commonest cause of death in the weekly obituary columns of the medical journals. This new disease clearly required a name. The cause, it seemed, was a clot of blood (or thrombus) in the arteries to the heart, which had been narrowed by a porridge-like substance, atheroma, made up of fibrous material and a type of fat called cholesterol. These are the âcoronary' arteries, for they form a âcrown' or corona at the top of the heart before passing over its surface to provide oxygenated blood to the heart muscle. Hence the blockage of one or other of these arteries with a thrombus became known as a âcoronary thrombosis' or simply âa coronary', better known as a âheart attack'.

The novelty of this epidemic of coronary disease was emphasised in 1946 by Sir Maurice Cassidy, the King's Physician, in the prestigious Harveian Oration. He first noted that the numbers dying from heart disease had increased ten-fold in just over a decade, and then confirmed that, from his own clinical experience, âcoronary thrombosis is far more prevalent than it was. Looking through my notes of patients seen twenty or more years ago, I come across occasional cases where I failed to recognise it, which now appeared to be the obvious diagnosis, but such cases are exceptionally few.'

7

And what could possibly be

the reason why apparently fit and healthy men in their forties and fifties should suddenly have their lives snuffed out in this way? Sir Maurice was puzzled. The presence of the atheroma in the coronary arteries that appeared to predispose to a heart attack is almost universal, certainly in the elderly in Western societies, so one would naturally expect coronary thrombosis to have been a common disease in the past, but it was not. On the contrary, the first description in Britain of the characteristic severe crushing chest pain followed by sudden death of a heart attack had been reported just twenty years earlier in 1925: âIn sudden thrombosis of the coronary arteries, there may occur a very characteristic clinical syndrome which has attracted little attention in Britain and which receives scant attention in the text books.'

8

It seemed to Sir Maurice that the key to the epidemic must lie in the clot or thrombus, but what precipitated it, he admitted, âis a problem I have failed to solve'.