The Parthenon Enigma (53 page)

Read The Parthenon Enigma Online

Authors: Joan Breton Connelly

The composition of the statue base has been reconstructed on the evidence of surviving copies and according to the testimony of

Pliny, who tells us that some twenty divinities were shown in the scene (insert

this page

, bottom, and following page, top).

124

From what we can understand, “Pandora” was shown at the center of the group as a small girl wearing a peplos, standing frontally with her arms hanging at her sides. Athena stands at the right with a stephane in her hand, ready to crown the maiden.

125

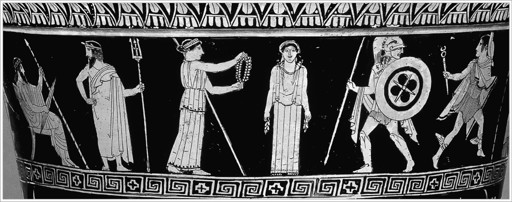

Two Athenian vases that predate the Parthenon show very similar imagery. On a red-figured krater in London we see a girl being crowned by Athena, while Zeus and Poseidon (to the left) and (to the right)

Ares, Hermes, and a female goddess (

Aphrodite or Hera?) attend the ceremony (following page, bottom).

126

Athena holds out a leafy wreath for the girl, who is dressed in a peplos and faces frontally, frozen and statue-like, clutching an olive (or laurel) branch in each hand. The maiden’s transfixed frontal gaze suggests the intensity of her altered state. She is isolated within the composition, separated by more than space in the very center of the scene, which has traditionally been interpreted as the creation of the first woman, Pandora. That reading, however, is frustrated by the absence of

Hephaistos, a key figure in the creation story, and the prominence of the war god Ares, who rushes in at the right in full battle dress. He is a companion figure here to the warrior goddess Athena, who stands at the left of the girl. The atmosphere is not one of creation but one of martial victory. We are reminded of Praxithea’s proclamation in the

Erechtheus:

“My child, by dying for this city, will attain a crown destined solely for herself.”

127

Here, then, is Athena awarding the promised crown to the daughter of Erechtheus following her sacrificial death. Running in from the battlefield, Ares bears news of the Athenian victory that this death has ensured.

Reconstruction drawing of the base of Athena Parthenos statue showing girl about to be crowned. By George Marshall Peters after N. Leipen,

Athena Parthenos

, Pl. 6. (illustration credit

ill.99

)

A similar female figure—shown in a frontal pose, arms hanging at her sides, and dressed in a peplos—can be observed on a white-ground cup (facing page) from Nola, near Naples. It too has been interpreted as showing the creation of

Pandora, as told by

Hesiod. We see Athena and Hephaistos reaching out to crown the girl from either side.

128

The maiden’s name is inscribed above her: “Anesidora,” meaning “She Who Sends Up Gifts,” a name very similar to Pandora, “Giver of All.”

129

But the name Anesidora carries a distinctly chthonic connotation, since her gifts are sent up from below. Indeed, the name suggests a dead girl buried within the earth.

130

It is very possible that a maiden named Anesidora, in some fifth-century tradition, comes to be known as Pandora by the time Pausanias writes in the Roman period. I submit that the base of the Athena Parthenos statue shows a crowning of

Erechtheus’s daughter, a girl variously named Anesidora/Pandora/Pandrosos. She is appropriately joined by Athena and Hephaistos, in a sense her “grandparents,” who caused the birth of Erechtheus/ Erichthonios. The deceased girl is shown welcomed into her new status as heroine, crowned, in the words of

Praxithea, with a wreath “destined solely for herself.”

Enthroned Zeus and Poseidon at left; Athena crowning daughter of Erechtheus at center; Ares and Hermes at right. Calyx krater, the Niobid Painter, ca. 460–450 B.C. (illustration credit

ill.100

)

Anesidora, at center, crowned by Athena and Hephaistos. White-ground cup from Nola, the Tarquinia Painter, ca. 460 B.C. (illustration credit

ill.101

)

If we take account of this special relationship between Athena and Pandora, understood to be the

parthenos

daughter of Erechtheus, certain persistent problems in Acropolis

ritual practice are resolved. For instance, the principle that “whoever sacrifices a cow to Athena is obliged

to sacrifice a ewe to Pandora [or Pandrosos].” This comes to us from Philochoros, who, having served as seer and inspector of sacred victims (

mantis

and

hieroskopos

) at Athens at the end of the fourth century

B.C.

, knew whereof he spoke. Surviving manuscripts give both variants of the name Pandora/Pandrosos.

131

Also this: the Parthenon’s south frieze shows cows alone being taken to sacrifice, reflecting Athena’s command that Erechtheus be honored with cattle sacrifices. The north frieze, by contrast, shows a combination of cows and sheep in procession. It is likely that the sheep sacrifice was destined for Erechtheus’s daughter, a girl alternately called Pandora, Pandrosos, or

Anesidora. The connection between Philochoros’s text and the Parthenon frieze has been noted before, but there has never been a plausible explanation for why a sacrifice should be made to Pandora within the context of Acropolis ritual.

This reading also helps shed light on a long-baffling passage in Aristophanes’s

Birds

. The soothsayer

Bakis pronounces an oracle that demands, “First sacrifice to Pandora a white-fleeced ram.”

132

The meaning of this oracle has never been understood. But if this Pandora is the benevolent Erechtheid of the Attic tradition, and not the problematic Pandora of Hesiod, things fall into place.

IF THERE IS ONE

more piece of the puzzle of the Panathenaia, of how the Athenians understood their great festival, it is a figure whose ubiquity renders it hidden in plain sight.

From the Panathenaic amphorae, to the famous silver tetradrachms that dominated Athenian coinage, to a host of images from Attic vase painting and sculpture, there is one symbol that is utterly synonymous with Athena. This is, of course, the owl. The inseparability of Athena and her winged companion has long been studied but never fully explained. Why is the owl so intimately associated with her? What is it about this particular creature that makes it the quintessential symbol of the goddess and, by extension, the city of Athens?

As a natural predator, the owl has a distinctly martial aspect that jibes with Athena’s role

as warrior goddess.

133

Again and again, we find the owl appearing on the battlefield to urge Athenian soldiers on to victory. In Aristophanes’s

Wasps

, we are told that Athena sent her sacred owl to fly over Athenian troops at Marathon, bringing them good

luck.

134

Plutarch writes of the difficulties Themistokles suffered in convincing the Greek allies to fight at Salamis—until, that is, an owl landed on the rigging of his trireme.

135

On Attic coins of the Roman imperial period Themistokles stands in full armor aboard his ship, a little owl alighting on its prow.

136

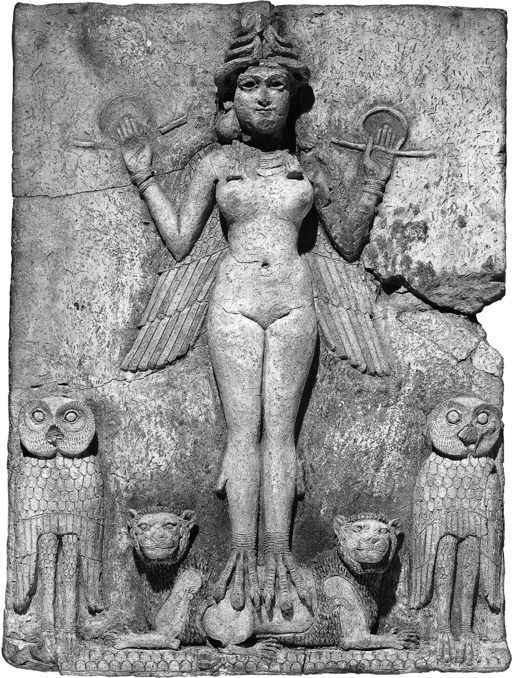

“Queen of the Night,” winged she-demon with talon feet; flanked by lions and large owls. Terra-cotta relief, Old Babylonian period, ca. 1800–1750 B.C. (illustration credit

ill.102

)

In Greek art, owls are regularly shown with their heads facing front, their bodies turned in profile. On a purely naturalist level, this manifests the exceptional range of rotation of an owl’s head and emphasizes the effect of its outsized eyes with their intense, unwavering gaze. Gloria Ferrari has explained that this straight-on stare was perceived as a masculine trait in ancient Greece (as it still is in some parts). Men looked at those whom they would confront straight in the eyes: bold, brash, and unafraid. Women, on the other hand, were expected to be “cow-eyed” (

boopis

) as Hera, queen of the gods, is so often described.

137

The female glance should be lowered, to express

aidos

, that is, “shame,” “modesty,” or “humility.”

Athena is called

glaukopis

, “owl-eyed,” as early as the seventh century in Homer’s

Iliad

and Hesiod’s

Theogony

.

138

This epithet could refer to the silvery, gleaming gray-green (

glaukos

) colors of her eyes or to her steely, unblinking gaze, as unusual for a female as Athena’s warrior aspect. Indeed, Athena Glaukopis is the most masculine of female divinities, and as goddess of war, wisdom, and craft she evinces no shame in her wide-eyed stare.

It must be acknowledged that frontal faces are quite rare in Archaic and classical Greek art.

139

The effect of this unusual perspective is purposefully arresting, to say that something out of the ordinary is happening. This invariably involves a physical or psychological transition between two states of being. Individuals caught between wakefulness and sleep, sobriety and drunkenness, silence and musical rapture, calm and sexual ecstasy, life and death, all look directly at the viewer, seizing upon a single moment suspended in time. We have noted in the images of Anesidora/Pandora that her full face is to the viewer as she experiences a kind of “apotheosis” through her crowning. At this moment the daughter of Erechtheus is caught between life and death, humanity and divinity. That Athena’s owl presents the same unsettling aspect is no coincidence. Death, indeed, hangs in the air.

Owls were understood to portend death as early as the Babylonian period in Mesopotamia, circa 1800–1750

B.C.

Consider the terra-cotta plaque known as the Queen of the Night, or the Burney relief (above), believed to be from southern Iraq. It shows a nude female figure with wings springing from her shoulders and bird talons on her feet. She perches atop two lions and is flanked by a pair of huge, menacing owls. The she-demon’s identity is much debated; suggestions include Lilîtu/Lilith, female demon of an evil wind and/or the night;

Innana/Ishtar, goddess of sexual love, fertility, and warfare; and

Ereshkigal, goddess of the underworld, Ishtar’s sister.

140

In her hands she holds the ring and rod symbols that signify the measurement of time by use of a string and stick.