The Parthenon Enigma (50 page)

Read The Parthenon Enigma Online

Authors: Joan Breton Connelly

The

anthippasia

involved a mock cavalry battle.

53

Riders from five tribes competed against those of the other five, arranging themselves in rows on horseback and riding through each other’s lines. This grand spectacle was evocative of the great battles of the epic past. So, too, were horseback javelin throws, which required contestants to hit a target while galloping at full speed.

54

Perhaps the most surprising of the tribal events, at least for the modern reader, is the male beauty contest.

55

Prizes for the

euandria

included an ox and, according to

Aristotle,

shields.

56

The ox suggests the entire tribe feasted together following the victory, which might mean that the

euandria

was a team event in which the beauty, size, and strength of one group of men were tested against those of groups from other tribes.

Xenophon tells us that the

euandria

at Athens was, as such things went, utterly “unmatched in quality.”

57

This competition celebrated the Athenian ideal of personal conduct known as

kalokagathia

, a compound of two adjectives,

kalos

(“beautiful”) and

agathos

(“good” or “virtuous”). We hear of one Athenian who won three separate events at the Panathenaia: the torch race, the

tragedoeia

(tragic acting competition), and the

euandria

. This man, it would seem, had it all: looks, strength, athleticism, acting talent, and, no doubt, a certain charisma.

58

One only wonders how well he played the kithara.

Just after sunset on the fifth day, the tribal torch races, or

lampadephoria

, were run. These seem to have been run by young ephebes, starting from out beyond the city walls in the Academy and speeding through the Dipylon Gate and the Agora, making their way up to the Acropolis.

59

This would have brought a thrilling visual display of firelight in the darkness, to say nothing of agility, speed, teamwork, and athleticism. Forty runners representing each of the ten tribes raced for

sixty meters in the relay, handing off the flaming torches until a distance of twenty-five hundred meters had been covered.

The torch race served the greater purpose of transferring fire from the

altar of

Prometheus in the Academy to the altar of Athena on the Acropolis. Thus, the event reenacted the stealing of fire and the lighting of the first sacrificial altar by Prometheus, father of King Deukalion and ancestor of all Athenians. The first runner to reach the Acropolis won the honor of lighting Athena’s altar for the sacrifices that would be offered there the next day. His tribe would share in the feast of an ox, as well as a hundred drachmas in cash. Each of the forty runners on the winning team received an additional thirty drachmas and a water jar.

60

LATER THAT EVENING

, citizen youths and maidens climbed the summit of the Acropolis for an all-night vigil, the

pannychis

, a most intense group experience.

61

For the girls, just past puberty, this was perhaps the first time they had ventured out from the confinement of their households at night to be in the company of young men. On the Acropolis rock they sang and danced the whole night through, no doubt taking turns in circle dances organized according to their tribes, dances that were a mainstay of their paideia from an early age.

It was through the repetitive movements of dance, set to music and the memorized words of

hymns, that young people learned the myth-histories of their community, perhaps why

Plato says that choral dancing represented “the entirety of education.”

62

Indeed, song-dance lay at the very heart of Greek paideia. As arms and legs moved to the beat of practiced notes and words, incorporated within the heightened intensity of ritual performance, the body found, as it were, its cosmic coordination point, locating the self within the incomprehensibly vast scheme of Athenian time and space. Who am I? Where do I come from?

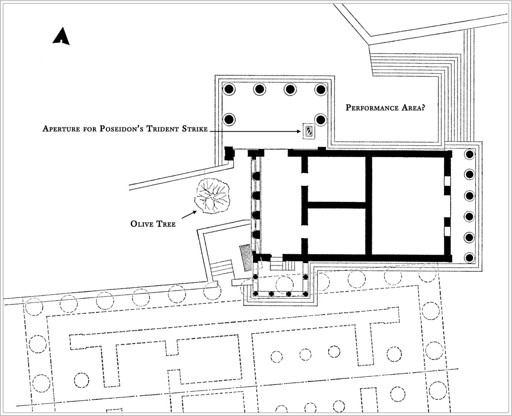

Where exactly on the Acropolis did the dances of the

pannychis

take place? While no surviving texts offer a conclusive answer, there is a basis for reasonable speculation. Between the north fortification wall and the

Erechtheion stretches a rectangular “plaza,” bounded at the west by the temple’s north porch and at the east by a flight of a dozen steps. This self-contained space would have been ideal for performance (facing page).

63

The steps and staircases looking down into the plaza would have served perfectly as “bleachers” for spectators. Fascinatingly, this square was paved over as early as the Bronze Age, indicating its use as a setting for spectacle might have been very long-lived.

64

It might well have been preserved across the ages as a special “theatral zone.”

Plan of Erechtheion showing location of Poseidon’s trident strike, Athena’s olive tree, and performance space. (illustration credit

ill.97

)

Shielded from wind and noise on four sides, this square offered ideal acoustics for choral singing and dancing. There was also its proximity to the mythically charged landscape of the Acropolis’s north slope, the very spot where the high drama of legendary princesses had played out. Here, above the cave of the Long Rocks, where

Apollo made love to

Kreousa and where the infant Ion was abandoned, girls might join hands in a circle dance on the eve of the Panathenaic procession. One might hear the piping of Pan drifting up from his cave in accompaniment, just as it had for the dances of the daughters of King Kekrops in the passage from Euripides’s

Ion

quoted in

chapter 1

.

65

And then there was the memory that the daughters of Kekrops and possibly the oldest daughters of Erechtheus leaped from the Acropolis cliffs to their

deaths.

66

Last, it is here within the ramparts of the north fortification wall that salvaged column

drums, metopes, and architrave blocks from the destroyed Archaic temples were displayed (

this page

). Landscape, myth, history, and ritual spectacularly collide in this uniquely charged place of memory.

Can we know what songs the girls sang as they joined hands in their choral dance? The beautiful choral ode of Euripides’s

Children of Herakles

may give us a hint. To be sure, it is sung by a chorus of old men, a rarity in Greek tragedy, but one that we also find in Euripides’s

Erechtheus

. Nonetheless, the ode may hold for us some vestige of the kinds of

hymns that might have been sung at the Panathenaia, including at the

pannychis

. The chorus invokes the full heavenly cosmos to join it:

O earth, O

moon that stays aloft the whole night long. O gleaming rays of the god that brings light to mortals, be my messengers, I pray, and raise your shout to heaven, to the throne of Zeus and in the house of gray-eyed Athena! For we are about to cut a path through danger with the sword of gray iron on behalf of our fatherland, on behalf of our homes, since we have taken the suppliants in.

…

But, lady Athena, since yours is the soil of the land and yours is the city, and you are its mother, its mistress, and its guardian, divert to some other land this man who is unjustly bringing the spear-hurling army here from Argos! By our goodness we do not deserve to be cast from our homes.

For the honor of rich sacrifice is offered to you, nor do the waning day of the month, or the songs of the young men or the tunes to accompany their dancing ever slip from our minds … On the windswept hill [of the Acropolis], loud shouts [

ololugmata

] resound to the beat of maiden dance steps the whole night long.

Euripides,

Children of Herakles

748–758, 770–783

67

There is much to gather here about the Panathenaic

pannychis

. At the very start of the hymn, the chorus invokes the celestial bodies of Earth, Moon, and Sun as messengers to Zeus. Later, it specifies the timing of the festival, that it begins “the day on which the moon wanes.” Indeed, the lunar

calendar shows a waning crescent moon for the twenty-eighth of

Hekatombaion. This would have made for very faint illumination of the Acropolis during the all-night vigil. The stars above would have been seen to shine all the more vibrantly.

The crescent moon is featured prominently on Athenian silver coinage, appearing on the earliest of the owl coins, minted in around 510–505

B.C

.

68

During the 470s, the crescent is introduced in the upper left field of Athenian tetradrachms, just beside Athena’s owl (

this page

). While this crescent has sometimes been interpreted as a reference to Athenian victories at Marathon or Salamis, this is unlikely.

69

We know the

Battle of Marathon took place under a full moon and, furthermore, that the crescent appeared on Athenian coins already in the last decade of the sixth century, well before the Persians landed on Greek shores.

The crescent moon may instead signal the Panathenaic festival and, in particular, the twenty-seventh through the twenty-eighth of

Hekatombaion, the night of the waning moon, when Athenian maidens and youths gathered on the Acropolis for their vigil. Euripides gives us a hint in the

Erechtheus

. A fragmentary line preserves a question the king puts to Praxithea, who appears to be handling some crescent-shaped wheat cakes: “Explain to me these ‘moons’ made from young wheat as you bring/take a lot of cakes from your house.”

70

Could such cakes have been offered as part of the rites of the Panathenaia? Were they fashioned into little “moons” to reflect the lunar aspect under which the festival culminated?

Importantly, Praxithea summons the women of Athens to sound the shrill cry of the

ololugmata

, beckoning Athena to be present: “Ululate, women, so that the goddess may come with her golden

Gorgon to defend the city.”

71

We are reminded of another priestess of Athena,

Theano of Troy, who, as she placed a peplos on the knees of Athena’s statue, was joined by the women of the city raising the ritual cry, “Ololu!”

72

And there is also a specific reference to

ololugmata

in the choral ode of

Children of Herakles

quoted on the previous page. Here, the “shrill cries” of the maidens resound to the beat of their dance steps.

The word

ololugmata

derives from the Greek verb

ololuzein

, meaning “to cry aloud,” and is related to the Sanskrit

ululih

, “a howling.” The English word “ululation” and the Gaelic

uileliugh

(“a wail of lamentation”) come to us through the onomatopoeic Latin

ululare

, meaning “to howl or wail.”

73

Indeed, the Latin word

ulula

means a kind of owl,

74

as does the Old English word

ule

.

Today, ululation is still customary among women in Africa, the eastern Mediterranean, the Arabian Peninsula, and India. The cry is most often used in weddings and funeral rituals. In the Muslim world, it is

specifically used at funerals of martyrs. Produced by the rapid movement of the tongue and the uvula while simultaneously emitting a shrill vocal scream, the sound is both alarming and haunting.

In the ancient Greek world,

women vocalized the

ololugmata

at moments of ritual climax.

75

In

sacrifice, it was unleashed at the very instant when the animal victim’s throat was slit. Like the sound of the

aulos, the women’s cries might have been a means of muffling the shriek of the dying animal. It is somewhat surprising to find the word used in the choral ode of

Children of Herakles

. Yes,

ololugmata

can be cries of joy, but they are certainly closely associated with death and sacrifice.

76

The deliberate use of this word could suggest here a dark message; the remembrances of this night, it seems, are not of unalloyed joy and light. Could the maidens have shouted the

ololugmata

to evoke the sacrifice of Erechtheus’s daughter, the girl whose throat was cut by her father upon Athena’s

altar? It is hard to imagine that, here, on the Acropolis rock, from which there is a tradition that the daughters of Kekrops and the older daughters of Erechtheus leaped to their deaths, Athenian maidens would not have been mindful of the sacrifice of the mythical princesses, commemorating them with song and dance.