The Parthenon Enigma (48 page)

Read The Parthenon Enigma Online

Authors: Joan Breton Connelly

Maps, plans, and models of ancient Athens, still and inert as they are necessarily, give little sense of the robust fields of movement that enlivened the city in antiquity. We are conditioned to experience “ruins” as static and unchanging, and so it is hard to grasp the vibrancy of ritual in action, the motion that once invigorated the placid scenes that we see today. We instinctively focus on the buildings when, in fact, the action took place in the spaces left between them. Temples were usually locked tight, serving as safe houses for valuable votive offerings and treasure. Life throughout the ancient Mediterranean, meanwhile, was lived mostly outdoors. Working, worshipping, dining, dancing,

even sleeping for much of the year, happened on verandas, under covered porticoes and grape arbors, in courtyards, on balconies, in streets, roadways, marketplaces, fields, and, yes, sanctuaries. It is therefore ultimately necessary to focus on the voids between structures, the open spaces that served as gathering places for spectacle and

performance. We will consider how these spaces were transformed by the actors and by the processions, dances, footraces, and rituals that brought life to them. Engaging with the ephemeral and performative aspects of Panathenaic ritual allows us to better understand the full dynamics of the process through which Athena was honored.

13

Such engagement suggests that in Greek antiquity the expenditure of energy through physical exertion constituted a prayer or votive act unto itself. Just as recent scholarship has encouraged us to view the act of writing, not just the inscription, as a votive, so, too, ritual movement can be understood as an offering that brought pleasure to the gods.

14

Loo

king cross-culturally at the Classic Maya, we find examples of the practiced, rapid movement of the feet—dance, in other words—constituting an attitude of prayer. Ritual foot shuffling summoned the essence of the divine.

15

The physicality of the human body was thus employed as an instrument of ritual communication. It is important to view the Panathenaia within this context. At Athens, we see the full citizenry of the body politic coming together with outsiders from across the Greek world in a grand kinetic offering to the goddess through marching, singing, reciting, running, jumping, throwing, wrestling, riding, sacrificing, and feasting.

BEFORE FOCUSING

on the Panathenaia itself, we would do well to consider the festival within the broader context of Greek

religion. We must remember that the Greeks had no “sacred book” to set down a universal system of beliefs and laws. They had no unified “church” with central authority, no “clergy” to instruct in beliefs. The Greeks did not even have a separate word for religion, since there was no area of life that it did not permeate.

16

Religion was embedded in everything. And it was wholly a local enterprise, dependent on the traditions of tightly knit family groups across many generations. Thus, every detail concerning religious practice was locally ordained. Each sanctuary had its own rules and regulations, guidelines for access, dress, comportment, festival

calendars, dedications, sacrificial practice, and hierarchy of sacred officials to oversee administration of sacred rites.

17

The Athenians, as we have said, were the most religious in a world steeped in religion. At Athens, it has been estimated that there were around 130 to 170 festival days per year, meaning more than a third of the calendar was devoted to observing religious feasts.

18

These offered the opportunity for eating flesh, a happy by-product of the

animal sacrifices offered to the gods (this is the “meat sacrificed to idols” against which Paul will later warn the Church at Corinth). By a convenient twist of mythological precedent, it was determined that gods preferred the inedible parts of sacrificial victims, the fat and bones, leaving the juicy cuts of meat to be shared by the human worshippers.

19

The absence of refrigeration meant that sacrificial meat from a large animal like a cow, bull, or ox had to be cooked and eaten on the spot. Meat was rarely eaten outside religious contexts, making for a “chicken every Sunday” way of life in which large family groups feasted together as part of sacred rites. At both the Great and the Small Panathenaic

festivals, where a hundred head of cattle were sacrificed, there was plenty to go around.

The musical and athletic contests of the Panathenaia were also part of the larger, overarching religious program. Athletic games were not the secular enterprises we know today, centered on the glory of the individual winner. The goal of the festival was to give honor to the goddess, to please Athena, and to remember the ancestors. So sacred was the athletic endeavor that a truce was called for the period before and during the

Olympic Games, known as

ekecheiria

, or “the laying down of arms.”

20

This allowed festival participants to travel safely to and from

Olympia over a three-month period. The same principle would have applied during the Great Panathenaia. In the months leading up to the feast, special ambassadors called

spondophoroi

were sent out to announce the competitions to Greek communities across the Mediterranean and as far east as the Arabian Gulf.

21

The Panathenaic Games stood out from the other Panhellenic contests for their lucrative cash prizes.

22

Those high-minded people had an appetite not merely for competition but for rewards of material value. The Athenian state paid out vast amounts to sponsor the games. So, too, did the oldest and most affluent families of the city, upon whom the expectation of benefaction rested very heavily. By the fifth century, however, Athenian allies and colonists were obliged to send a cow and

a panoply of weapons for the Great Panathenaia.

23

Thus, the financial burden came to be more broadly shared.

From the mid-sixth century on, prizes for the Panathenaia took the form of precious Athenian olive oil held in vessels specially commissioned by the state. Known as

Panathenaic prize amphorae, these vases conform to particular specifications of size, volume, shape, and decoration.

24

On one side, they show Athena helmeted in her full martial guise, brandishing her spear and shield and striding aggressively forward. In painted letters beside the picture panel appear the words “From the Games at Athens,”

TON ATHENETHEN ATHLON

. Some idea of the value placed on winning in the Panathenaic Games can be understood from the size of the prizes. Panathenaic amphorae held exactly thirty-six kilos of olive oil. We hear of one winner who received 140 amphorae, five tons of oil in all. The value of that quantity has been estimated at 1,680 drachmas, roughly five and a half years’ salary for the average worker.

25

The exorbitant compensation of star athletes is one of our lesser-known Athenian legacies.

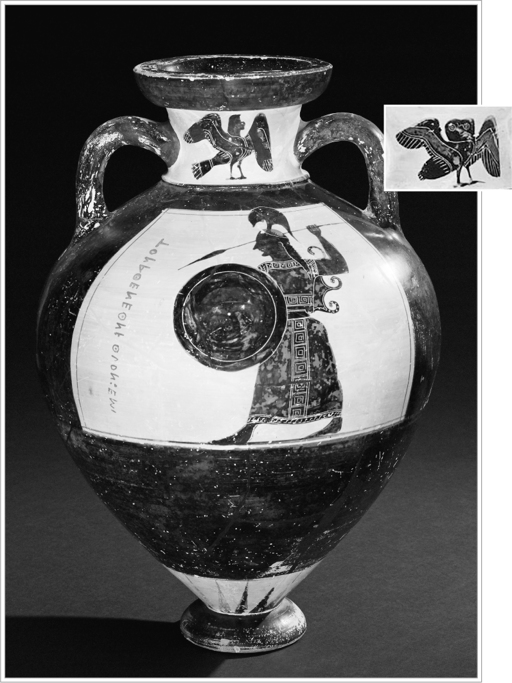

An amphora from the so-called Burgon group, dating to around 560

B.C.

, represents the earliest in the sequence of prize amphorae (previous page).

26

Athena is shown striding forward on the belly of the vase,

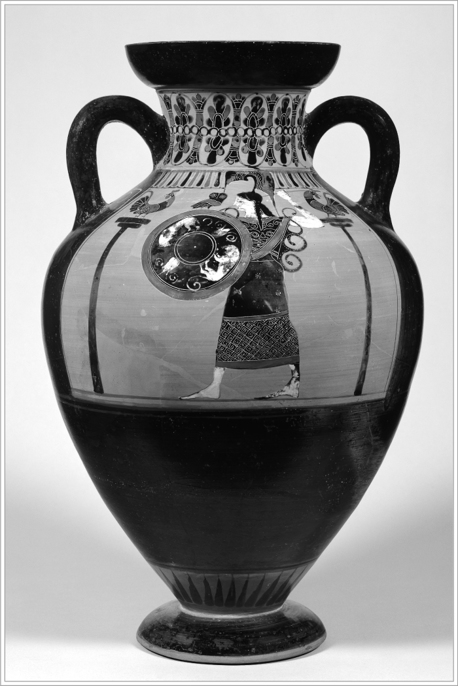

with a bird-bodied siren on one side of its neck and an owl on the other. It is of great interest that the two winged creatures, both associated with mourning and lament, are paired together on this very early Panathenaic prize amphora. By the 540s, a canonical image is established for Panathenaic amphorae, one that shows Athena striding forward and flanked by two columns surmounted by cocks; a vase by the

Princeton Painter follows this Panathenaic model (below).

27

By now, the goddess’s iconic mascot, the little owl, has come to perch upon her shield. We shall soon have more to say about the persistence of winged creatures within the orbit of Athena, where they have very special significance.

Panathenaic prize amphora with Athena brandishing spear and shield; siren on neck, owl on reverse of neck. Burgon type, ca. 566 B.C. (illustration credit

ill.94

)

The reverse side of Panathenaic vases regularly shows images drawn from the musical and athletic competitions. The Burgon, for example, shows a two-horse chariot race known as the

synoris

. Straight through the Hellenistic period, Panathenaic amphorae will continue to be decorated in the black-figured technique of the sixth century. Thus, they maintain an Archaic look, deliberately evoking the earliest days of the festival.

While the precise event schedule of the Great Panathenaia is not

known for certain, it is believed that the feast was celebrated across eight days, from roughly the twenty-third to the thirtieth day of the month

Hekatombaion.

28

Athens, like many Greek cities, had its own names for months. Hekatombaion means an offering of “one hundred”

animal victims, referring to the number of cattle sacrificed at the Panathenaia. Athenian Hekatombaion falls roughly from the middle of July to the middle of August in our

calendar. The Panathenaic festival would thus have taken place during the final eight days of the month, culminating in procession and sacrifice on the twenty-eighth of Hekatombaion, or, around the fifteenth of August. In time, this day came to be recognized as the

birthday of Athena.

29

The legacy remains with us: our month of August falls under the zodiac sign of

Virgo, the Virgin. And in both the Catholic and the Orthodox traditions, the fifteenth of August is celebrated as the greatest feast of the

Virgin Mary, the day on which she was taken up bodily into heaven.

Amphora of Panathenaic shape and iconography, showing Athena brandishing a spear and a shield (on which an owl alights). Princeton Painter, ca. 540s B.C. (illustration credit

ill.95

)

The schedule of athletic events for the Gre

at Panathenaia can be reconstructed, up to a point, thanks to the survival of lists of prizes for winners given in order of their victories. These are preserved on a key inscription dated around 380

B.C.

30

Of course the inscription attests to practices of the early fourth century and may not reflect those in other periods of the festival’s more than eight-hundred-year history; however steeped in tradition, the Panathenaic festival was by no means static or unchanging. Events and venues were added and eliminated across the centuries. Nonetheless, we can confirm that by the fourth century the festival program ran across eight days.

The first day was devoted to musical contests and the recitation of poetry, the second day to athletic competitions for boys and youths, the third day to men’s athletic contests, and the fourth to equestrian events. The fifth day began the tribal contests open to Athenian citizens alone, and carried over into the sixth on which the torch races and the all-night vigil on the Acropolis, the

pannychis

, took place. (It should be said that this all-night revel may have taken place later in the week, following the sacrifices and feasting.)

31

The seventh day saw the great procession and sacrifices on the Sacred Rock, followed by more tribal competitions, the

apobates

and boat races, on day eight. While it is not known precisely when the prizes were awarded, it is assumed that this took place on the final day.

Let us imagine the experience of participants over this week of festivities.

Around the twenty-third of

Hekatombaion, worshippers gathered for musical competitions and recitations of epic and lyric poetry that signaled the start of the Panathenaia. Indeed, music may have served to summon the essence of the divine, inviting the goddess’s presence for the week of events offered in her honor. We must not mistake the primary function of music

in sacred ritual: it is a means of communicating with the divine, bringing the community together in a shared experience that transcends the quotidian, an altered state of being.