The Parthenon Enigma (22 page)

Read The Parthenon Enigma Online

Authors: Joan Breton Connelly

Turning to the north side of the pediment, we find a comparable group: three female figures, the standout being a spectacularly voluptuous woman (figure M) shown collapsing into the arms of a companion (figure L) who holds her from behind (following page and insert

this page

, left). The two figures are carved from a single piece of marble and rest together upon a low couch. It is no wonder that the sultry woman has been identified as that most erotic of female divinities,

Aphrodite. Diaphanous drapery reveals the fullness of her body as “ribbons” of delicate fabric frame her swelling breasts and abdomen, with great swaths of cloth swirling about her legs. The goddess’s chiton slips to reveal her soft right shoulder, while the transparency of the fabric at her breasts allows the areolae to show through.

Interpreters have long debated the identity of Aphrodite’s two companions. Most see her mother,

Dione, in the woman (figure L) who supports her from behind, though others have suggested

Artemis,

Peitho

(Persuasion),

Themis (Justice), one of the goddesses of the seasons (

Horai), or one of the

Hesperides. The woman (figure K) who sits on a rock, just behind the pair, has been identified as

Hestia (goddess of the hearth),

Leto,

Amphitrite, one of the goddesses of the seasons (Horae), or one of the Hesperides. This range of opinion makes plain that we really do not know who these women are.

74

In any case, the possible contenders include characters hardly prominent within the ranks of the Olympians who might have witnessed the birth.

It must be acknowledged that this composition is strange; never before had Aphrodite been shown in the lap of a woman, and no subsequent instance is known. The low bed on which the voluptuary collapses in so many ways evokes the

birthing couches depicted in Cypriot stone sculpture and, closer to home, on Attic grave reliefs.

75

The attendant who holds her from behind assumes the standard pose of midwife. Taken as a pair, the two women with Aphrodite could be seen as the

Eileithyiai, the goddesses of childbirth (who are always present at the birth of

Athena). One is known as “she who delays,” the other as “she who urges” the moment of birth. Indeed, they are suitably arranged to perform this function for the blooming, reclining one. And so we could propose (though purely speculatively) that “Aphrodite” is, actually,

Metis, consort of

Zeus and mother of Athena. Though she does not physically give birth to the goddess, she appears figuratively post labor.

For the

genealogical sense of the scene requires that she be present. After all, this goddess of cunning intelligence must pass on these faculties to her daughter, the goddess of wisdom.

76

East pediment, voluptuous female figure reclines on a low couch, attended by two women (figures K, L, and M). (illustration credit

ill.33

)

The

west façade of the Parthenon, and the twenty-five larger-than-life figures that fill its gable, would have been the first sight to confront worshippers emerging from the Acropolis gateway and entering the sacred space (insert

this page

, right). This first impression manifests on a grand scale the common

genealogy of the Athenian people, that which made their supremacy possible. We see the primeval contest of Athena and

Poseidon for patronage of the city as witnessed by the ancestral royal families of the Athenian

Bronze Age. The gable suffered greatly in the Venetian cannon fire of 1687, and also from the Venetian commander General Morosini, who, the following year, attempted to pull down the images of Athena and Poseidon, only to shatter them upon the ground. More than a century later,

Lord Elgin would pick up some of the pieces and carry them off. But other bits were left lying on the Acropolis, and so today the magisterial figures of Athena and Poseidon remain divided between the

British Museum in London and the

Acropolis Museum in Athens.

One can hardly imagine a more fitting commemoration of Athena’s victory over Poseidon than the thrilling composition at the very center of the gable, where god and goddess meet in the heat of the contest.

77

Thanks to the

Nointel Artist, and derivative images from Greek vase paintings, we have a good idea of the original disposition of the figures in a dynamic V shape.

78

The divine contestants have arrived on the Acropolis, Athena’s chariot driven by Nike (foretelling her victory) and Poseidon’s by a female figure who must be his wife, the Nereid

Amphitrite.

79

Athena’s right arm is raised high as she hurls her spear into the Acropolis rock, whence springs her olive tree. Though no tree is preserved among the pedimental fragments, fourth-century vase painting, clearly inspired by this image, shows an olive sprouting between Athena and Poseidon.

80

The sea god, in turn, hurls his trident into the bedrock. Whether we are witnessing the sea spring bursting forth or the subsequent earthquake and

deluge that the disgruntled Poseidon unleashed is difficult to know. What is clear is that this bombastic central composition could not have failed to seize the attention of anyone entering the Acropolis.

Relics from the contest of Athena and Poseidon are not only described

in literature but preserved in material remains on the Acropolis itself.

81

Apollodoros tells us that Athena planted her olive tree in the sanctuary of

Pandrosos, which lay just beside the

Erechtheion;

Pausanias saw the tree growing near the north porch, where a modern incarnation of the olive grows today (below).

82

And he tells us that on the day following the Persian sack of the Acropolis, Athena’s tree sprouted a new branch four feet long, signaling that Athens would be reborn. Over the years, invading enemies attempted to cut the olive down, but a sprig was always saved for replanting, and the tree always grew back. Shoots from the original were carried out to the Academy and planted in the protected grove that remained ever sacred to Athena. Indeed, it was oil from these trees that filled the amphorae awarded victors at the Panathenaic Games.

Poseidon’s gift of a sea spring was heard by Pausanias, roaring from its cistern beneath the Erechtheion, in a din of crashing waves that kicked up whenever a south wind blew. And with his own eyes the traveler saw three holes piercing the Acropolis rock, where Poseidon had hurled his mighty trident, a witness also borne by Strabo.

83

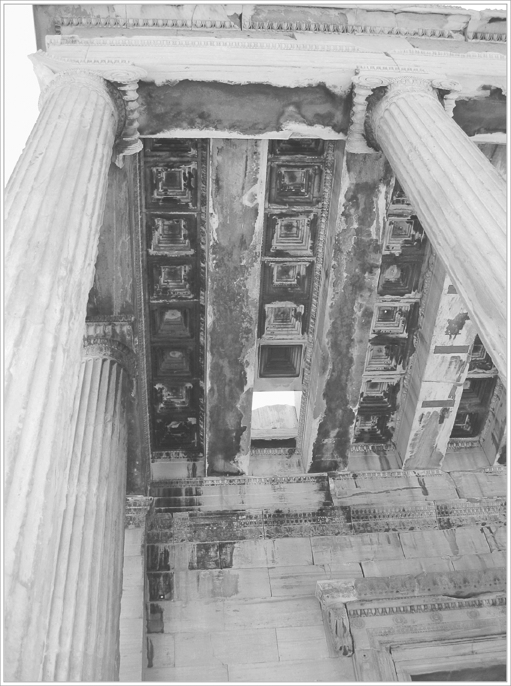

To this day, one can see a three-pronged indentation in the bedrock beneath the Erechtheion’s north porch, visible through an opening deliberately cut through the floor.

84

High in the ceiling, directly above, is an aperture cut through the coffer blocks giving direct access to the sky (above). Thus, the trajectory of Poseidon’s trident was left unbroken when the temple was built upon the very spot where the god’s spear pierced the earth, the trident marks and sea spring giving, as Pausanias tells it, “evidence in support of Poseidon’s claim upon the land.”

85

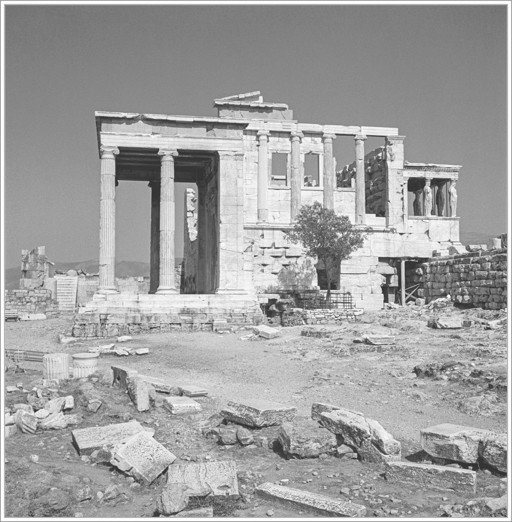

Erechtheion, from west, showing olive tree of Athena replanted by the American School of Classical Studies at Athens in 1952. © Robert A. McCabe, 1954–55. (illustration credit

ill.34

)

Aperture in ceiling of north porch, Erechtheion, Athenian Acropolis. (illustration credit

ill.35

)

Returning to the west pediment (insert

this page

, right), we find the messenger gods

Hermes (behind Athena) and

Iris (behind

Poseidon) rushing to bring word of the outcome of the contest. Iris, the rainbow

goddess of sea and air, would have hovered slightly, her feet just off the ground, her diaphanous dress windswept to reveal the swelling form of her lovely body. She is the very essence of the ephemeral rainbow, a cosmic phenomenon that witnessed the very beginnings of Athens.

Similarly, watery depths are conjured, just as on the

Archaic Acropolis, by a plethora of marine serpents and slithering snakes. In the Nointel drawing, a male torso, probably that of a

Triton, can be made out rising from the pediment floor to support the outermost of Athena’s horses. And beneath Poseidon’s chariot, we find a similar Triton buoying up a yoked horse, his finned and snaky tail curling up from the watery depths. We see, too, a wonderful-looking

ketos

—a vicious sea beast with porcine snout and huge, deadly teeth—skimming the water’s surface while supporting the left foot of

Amphitrite as she drives the chariot. Together with the snake lurking by Kekrops’s leg (

this page

), and that which probably circled Athena’s olive tree, these creatures manifest a contrast of earth and water embodied in Athena and Poseidon themselves.

The corners of the west pediment are inhabited by figures that have long been identified as the great rivers of Athens, the Kephisos, Ilissos, and Eridanos.

86

This interpretation conforms with the

east pediment of Zeus’s temple at Olympia, where the two local rivers, the Alpheios and the Kladeos, lie in the corners of the gable, as

Pausanias confirms during his visit.

87

The river gods on the Parthenon similarly serve to establish the topographical coordinates of the contest on the Athenian Acropolis. The grand Kephisos is shown at the very north (or left) side (facing page), lying beside its younger tributary, the Eridanos, known from the Nointel drawings. At the opposite (south) end of the gable the Ilissos kneels just beside a female figure that is the

spring of Kallirrhöe (insert

this page

, right) in another topographically correct arrangement.

But the river gods of the west pediment serve a purpose far beyond spatial orientation; indeed, they are integral to the

genealogical message of the sculptural program as a whole. The Kephisos River was the father of the naiad nymph

Praxithea, who married King Erechtheus and became queen of Athens and mother to a generation of royal daughters. And so the presence of the Kephisos here further validates the Athenian claim upon the land of Attica: not only are Athenians autochthonous, descendants of the gegenic Kekrops and Erechtheus/Erichthonios, but on the maternal line they are descended from Athens’s greatest river.

There is little consensus about the figures that fill out the rest of the gable.

88

Barbette Spaeth suggests that at left (north side) are the descendants of the Athenian royal house while at right (south side) are the dynastic family of Eleusis.

89

And so the descendants of Athena inhabit the space behind her while the offspring of Poseidon crowd the space behind him. This would be wholly in keeping with the larger genealogical project of architectural sculpture seen on the Acropolis from the Archaic period on.