The Parthenon Enigma (21 page)

Read The Parthenon Enigma Online

Authors: Joan Breton Connelly

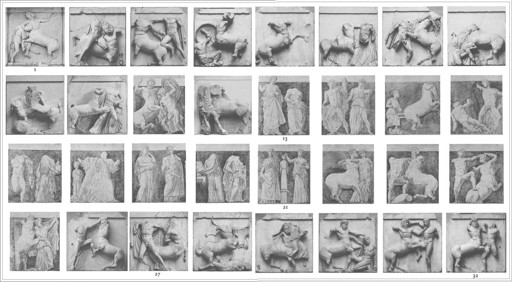

Meanwhile, the south metopes present a conflict from a later moment of the mythical past, the second

Bronze Age, in which the Athenian hero

Theseus helps his friend

Peirithoös (king of the

Lapiths) in subduing the monstrous Centaurs. A fight breaks out at the king’s wedding feast when the Lapiths’ neighbors, half man/half horse, get wildly drunk (inexperienced imbibers as they are) and attack the bride and bridesmaids as well as the Lapith men, who try to defend the ladies’ honor. This boundary event was very popular in Greek architectural sculpture, prominently featured (two decades earlier) on the west pediment of the Zeus temple at Olympia. The Centauromachy serves as a rousing metaphor for the triumph of civilization over barbarism, of order over chaos, just as the Gigantomachy and Titanomachy of earlier ages do.

62

On the Parthenon metopes, the Greeks are shown wielding swords and daggers (accentuated by metal attachments) as they battle the savage Centaurs, who fight back with water jars and barbecue spits, indeed, with their bare hands and hooves. Vibrant paint and a full array of bronze attachments (helmets, crowns, and weapons) lent flash and definition to the carvings.

For much of this understanding, we are indebted to

Charles François Olier, the Marquis de Nointel (French ambassador to the Ottoman court from 1670 to 1679), and his team of artists who drew these metopes, and the rest of the Parthenon sculptures, during their visit to the Acropolis in 1674. Just eleven years later, Venetian cannon fire would blow the temple apart, destroying much of what the marquis had seen. The careful crayon drawings that remain, sketched looking up from ground level, are regularly attributed to a single member of the team, the Flemish artist

Jacques Carrey. In fact, we do not know the exact identity of this hand, and many scholars prefer to call him the

Nointel Artist or “l’Anonyme de Nointel.”

63

When the seventeenth-century drawings are integrated with photographs of the surviving south metopes (all in the

British Museum except one left behind by Elgin at the southwest corner of the Parthenon), a full range of forms and subject matter becomes apparent (following pages).

64

The compositions of the easternmost of the south metopes (29–32) reveal the telltale awkwardness in the rendering of figures in relation to one another. Greek warriors look staged, their stiff poses lacking harmony

and grace: hopping on one foot, facing the viewer while harmlessly pinching a Centaur’s chest, pulling at a Centaur’s ear (?). The Centaurs are equally clumsy: grabbing an unwieldy

Lapith woman in awkward abduction, and reduced to hair pulling and throat grabbing in fighting the Lapith men. But when we turn to the adjacent

metopes (27–28), we see a whole different level of sophistication and competency in the harmonious integration of elegant figures into the compositional whole. Even the Centaurs look noble. This disparity in style and execution has led some to believe that the “old-fashioned” metopes had been carved for an earlier building altogether and simply reused here.

Rhys Carpenter

maintained that those “behind the times” panels were carved for a

Kimonian Parthenon, planned and prepared in the 460s but never realized (hence the similarity to decorations at the

temple of Zeus at Olympia).

65

He and others have pointed to the fact that more than half of the south metopes have had one or both end surfaces cropped to make the slabs about 5 centimeters (2 inches) narrower. Indeed, on four metopes the borders have been shaved so much as to snip the tails of two Centaurs, as well as Lapith drapery and other relief details. All this suggests that some of the south metopes had to be reduced in size to fit here.

Battle of the Lapiths and Centaurs, south metopes, Parthenon. (illustration credit

ill.32

)

And then there is the baffling question of the nine metopes in the

very center of the south side (13–21, known only through the Nointel drawings) that lack Centaurs altogether (previous pages). These show women taking refuge at a

cult statue,

Helios driving his chariot (?), women with some item of furniture (a loom or bed?), dancing figures, and other images that seem strange within the context of the Centauromachy. Scholars have offered various speculative interpretations, some assigning these panels to the

Lapith wedding feast preceding the drunken brawl, others arguing for wholly unrelated subject matter, such as the myth of

Daidalos.

66

All this suggests a number of changes to the design and decoration of the Parthenon in the course of its construction.

Manolis Korres has now established that the

Ionic frieze within the Parthenon’s colonnade originally extended all the way around the front porch. He has reiterated Dörpfeld’s view that the original plan called for this inner frieze to be

Doric (one of alternating triglyphs and metopes, just as we see on the exterior of the Parthenon).

67

The

regulae and

guttae (a band with truncated cone ornaments, which typically appear under triglyphs) visible just beneath the

Parthenon frieze represent preparations already in place when, for whatever reason, a change was ordered calling for an Ionic frieze instead. This view has been challenged, but it remains clear that decisions were reversed and altered while the Parthenon was being built, perhaps reflecting democratic deliberation.

68

Certainly the Parthenon is not the vision of a single genius, and there was lively discussion and debate in the citizen assembly, if only because every expense had to be approved. But the possibility of a decision to replace a planned Doric frieze with a continuous narrative band, one that would achieve such renown as to be eventually known simply as

the

Parthenon frieze, merits close attention. For as we shall see in the next chapters, it is this frieze—whose claim to being the greatest masterpiece in all of Greek art is so strong but whose meaning has remained so obscure—that articulates the most startling of all the Parthenon narratives. It is this frieze that is at the heart of the temple’s ultimate meaning.

THE WEST METOPES

(so badly damaged one can barely make them out) present yet another of

Theseus’s exploits, the battle of the Greeks and the Amazons. This conflict was provoked by Theseus’s abduction of the Amazon queen,

Antiope, whom he carried off from north-central

Anatolia to Athens and married. Enraged, her tribe of warrior women stormed all the way from the southeast corner of the Black Sea to wage war with the Athenians. By some accounts, the

Amazon siege of the Acropolis was launched from a camp they set up on the Areopagus Hill, just as the Persians will do in historical times. The west metopes show mounted Amazons furiously battling (and killing) Greeks.

69

But, once again, there emerges a tale of civilized Hellenes defeating exotic “others,” in this case, savage fighting women from the East, a thinly veiled reference to the Athenian triumph over the Persians.

The north metopes present yet another parable of triumph over eastern exotics, in that greatest boundary event at the end of the

Bronze Age: the

Trojan War. Once again, we find

Helios driving his chariot, here, appropriately in the easternmost panel, just around the corner from the Helios metope of the temple’s east façade, where the morning light would first strike the Parthenon. The north metopes have suffered greatly, but one can make out a sequence of events from the night Troy fell: the

Moon’s chariot setting into the sea; men at the stern of a ship; Menelaos, who led the Spartans, drawing his sword as he approaches his unfaithful wife, Helen, who has taken refuge at the statue of Athena;

Aphrodite (little Eros upon her shoulder) persuading Menelaos to spare his wife;

Anchises,

Aeneas, and Ascanios escaping from Troy; while Athena, Zeus, and other Olympians play their parts.

WERE IT NOT FOR

Pausanias’s telling us that the east

pediment shows the birth of Athena, we would never have guessed it from the few surviving figures. Most of the pediment was dismantled long ago, some of it as early as the fifth century

A.D.

, when the Parthenon was transformed into a church. This required the addition of an apse, which extended through the center of the east façade, interfering with the sculptured pediment and frieze (

this page

). The Nointel drawings show the gable’s condition in the seventeenth century with only its corner figures in situ (insert

this page

, left). These, of course, would later be taken by Elgin, except for a draped female figure (Hera?) and a male torso (Hephaistos?), which were later discovered among the Acropolis stones.

Two powerful chariot groups frame the pediment as the rising Sun (Helios) drives his quadriga up from the waters at the south corner and the setting Moon (Selene) steers her horses into the sea at the north.

These personifications effectively demarcate Athena’s birthday, setting it in the remote past of

Hesiod’s Golden Age. The upper torso of Helios and the heads of his horses emerge from a tempestuous sea, whose choppy waves can be seen atop the plinth from which they arise. The imagery gives palpable form to the

First Homeric Hymn to Athena

, which describes the moment of her birth: “A fearsome tremor went through Great Olympos from the power of the Steely-eyed one [Athena], the earth resounded terribly round about, and the sea heaved in a confusion of swirling waves. But suddenly the main was held in check, and Hyperion’s splendid son [Helios] halted his swift-footed steeds for a long time, until the maiden,

Pallas Athena, took off the godlike armor from her immortal shoulders, and wise

Zeus rejoiced.”

70

The prominence of celestial bodies in the Parthenon sculptures is striking. We have already witnessed the arrival of Helios in the Gigantomachy

metopes of the east façade, and we have noted both Helios and Selene in the metopes at the north, marking the day of the fall of Troy. Now, on the great east gable, we see the pair prominently featured, and we shall see them once again, on the base of Athena’s statue within the Parthenon’s cella (insert

this page

, bottom).

71

These multiple appearances of Sun and Moon reinforce a cosmic

awareness already expressed on the

Archaic Acropolis: the unity of the celestial and the terrestrial, from which the city’s greatest mythological narratives were conceived.

The very center of the pediment, where we should find the culminating moment of Athena’s birth, is forever lost (insert

this page

, left). We might imagine it showed something like what is described in the

Homeric Hymn to Athena:

“Of Pallas Athena, glorious goddess, first I sing, the steely-eyed, resourceful one with implacable heart, the reverend virgin, city-savior, doughty one,

Tritogeneia, to whom wise Zeus himself gave birth out of his august head, in battle armor of shining gold: all the immortals watched in awe, as before Zeus the goat-rider she sprang quickly down from his immortal head with a brandish of her sharp javelin.”

72

While the

birth of Athena is represented in vase paintings of the sixth and fifth centuries, the east pediment of the Parthenon marks its first appearance in architectural sculpture. Based on images from vases, we might expect to find an enthroned Zeus beside Athena (as a full-grown adult in full armor) at the center of the composition, flanked by

Hephaistos holding the ax that cracked Zeus’s throbbing head and induced the birth.

Poseidon,

Hermes, and

Hera might be standing by, and certainly one or both of

the twin goddesses of childbirth, the

Eileithyiai, who are regularly shown assisting in the “labor.” Many reconstructions have been hypothesized across the years, but, truth be told, we simply cannot know how the central (missing) figures were arranged.

73

What does survive of the east pediment are four figures from the south side and three from the north, flanked at the corners by the chariots of the Sun and Moon (insert

this page

, left). The reclining male (just to the right of Helios’s horses) has been identified on the basis of the feline skin on which he sits as either

Dionysos (if a panther) or

Herakles (if a lion). Both god and hero are known in Greek art to assume the recumbent pose of a banqueter; indeed, both are often shown lifting a cup as this figure on the east pediment seems to do. Since he looks away from the central action and down in the direction of the

Theater of Dionysos on the Acropolis’s south slope, most interpreters identify him as the god of theater, attending the birth of Athena but distracted by his own cult place below.

Dionysos also turns his back on a pair of female goddesses,

Demeter and Kore, who sit upon boxes that surely represent the

kistai

, containers holding the “sacred things” used in the

Eleusinian Mysteries. Kore (figure E), at left, wraps her arm lovingly around her mother, Demeter (figure F). To their right, a goddess rushes toward the center of the action, her arms raised high (figure G). This is likely

Hekate, goddess of the night, lifting her torches, which would make for a cohesive group of interrelated chthonic deities here at the southern corner.