The Oxford History of World Cinema (50 page)

Read The Oxford History of World Cinema Online

Authors: Geoffrey Nowell-Smith

get under way, ironically from the Russian émigré company Albatros. The initial model of

comedy construction was to update the figure of the naïve provincial come to the

sophisticated capital, as in Volkoff's Les Ombres qui passent ('Passing shadows', 1924).

Another was to transpose American gags and even characters into an atmosphere of

French gaiety, as in the Albatros series starring Nicholas Rimsky, or in Cinéromans's

Amour et carburateur ('Love and carburettor', 1926), directed by Colombier and starring

Albert Préjean. The real accolades, however, went to Clair for his brilliant Albatros

adaptations of Eugène Labiche, Un chapeau de paille d'Italie (The Italian Straw Hat,

1927) and Les Deux Timides ('The timid ones', 1928), with ensemble casts featuring

Préjean, Pierre Batcheff, and Jim Gerald. Accentuating the original's comedy of

situations, Clair's first film thoroughly mixed up a wedding couple and an adulterous one

to produce an unrelenting attack on the belle ipoque bourgeoisie through a delightful

pattern of acute visual observations. Almost as successful was Feyder's Les Nouveaux

Messieurs ('The new gentlemen', 1928), which provoked the ire of the French

government, not for its satire of a labour union official (played by Präjean), but for its so-

called disrespectful depiction of the National Chamber nto an exuberant social satire,

pitting a blithely assured but ineffectual bourgeois master against his bighearted,

bumbling servant, played with grotesque audacity by Michel Simon.

By the end of the decade, the French cinema industry seemed to evidence less and less

interest in producing what Delluc would have called specifically French films. Whereas

the historical film was frequently reconstructing past eras elsewhere, the modern studio

spectacular was constructing an international no man's land of conspicuous consumption

for the nouveau riche. Only the 'realist' film and the comedy presented the French

somewhat tels qu'ils sont -- if not as they might have wanted to see themselves -- the one

by focusing on the marginal, the other by invoking mockery. With the development of the

sound film, both genres would contribute even more to restoring a sense of 'Frenchness' to

the French cinema. Yet would that 'Frenchness'be any less imbued with nostalgia than was

the charming repertoire of signs, gestures, and songs that Maurice Chevalier was about to

make so popular in the USA?

Bibliography

Abel, Richard ( 1984), French Cinema: The First Wave, 1915-1929.

--- ( 1988), French Film Theory and Criticism: A History/Anthology, 19071929.

--- ( 1993), The Cinf Goes to Town: French Cinema, 1896-1914.

Bordwell, David ( 1980), French Impressionist Cinema: Film Culture, Film Theory and

Film Style.

Chirat, Raymond, and Icart, Roger (eds.) ( 1984), Catalogue des films français de long

métrage: films de fiction, 1919-1929.

--- and Le Eric Roy (eds.) ( 1994), Le Cinéma français, 1911-1920.

Clair, René ( 1972), Cinema Yesterday and Today.

Delluc, Louis ( 1919), Cinéma et cie.

Epstein, Jean ( 1921), Bonjour cinéma.

Guibbert, Pierre (ed.) ( 1985), Les Premiers Ans du cinéma français.

Hugues, Philippe d', and Martin, Michel ( 1986), Le cinéma français: le muet.

Mitry, Jean ( 1967), Histoire du cinéma, i: 1895-1914.

--- ( 1969), Histoire du cinéma, ii: 1915-1923.

--- ( 1973), Histoire du cinéma, iii: 1923-1930.

Moussinac, Léon ( 1929), Panoramique du cinéma.

Sadoul, Georges ( 1951), Histoire générale du cinéma, iii: Le cinéma devient un art, 1909-

1920 (l'avant-guerre).

--- ( 1974), Histoire générale du cinéma, iv: Le cinéma devient un art, 1909-1920 (La

Première Guerre Mondiale).

--- ( 1975a), Histoire générale du cinéma, v: L'Art muet (1919-1929).

--- ( 1975b), Histoire générale du cinéma, vi: L'Art muet (1919-1929).

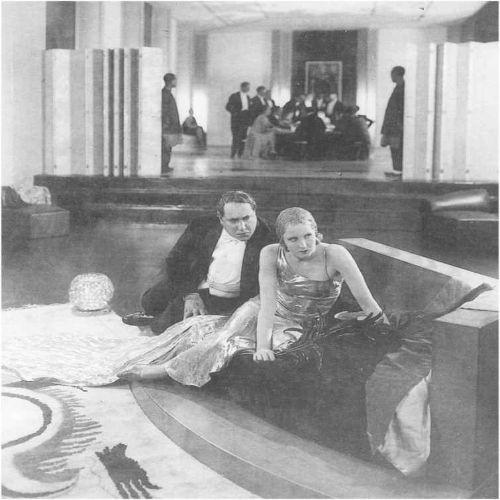

Saccard (Alcover) and Sandorf (Brigitte Helm) in Marcel L'Herbier 's L'Argent ( 1929)

Séverin-Mars in Abel Gance 's La Roue ( 1921)

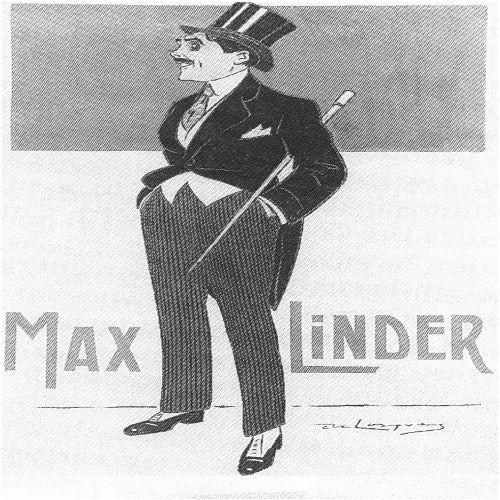

Max Linder (1882-1925)

Max Linder was one of the most gifted comic artists in the history of the performing arts.

Inscribing a photograph to him in the early 1920s. Charlie Chaplin called him 'The

Professor-to whom I owe everything'; and there is no doubt that Linder's style and

technique were a great influence on Chaplin, as indeed upon practically every other

screen comedian who followed him, whether or not they were aware of it.Born Gabriel

Leveille to a farming family near Bordeaux. Linder was stage-struck from childhood. He

studied at the Bordeaux Conservatoire, and acted in Bordeaux, and later in Paris with the

company of Ambigu. In 1905 he began to augment his salary by working by day at the

Pathé studios. The shame of working in moving pictures was concealed by using the nom

d'art Max Linder. In the course of two years he made his mark as a light comedian; and

when Pathé's first great comedy star André Deed defected to the Itala Studios in Turin,

Linder starred in his own series. The first of these films were tentative, but during 1910

the eventual max character evolved rapidly.While the other comic stars of the period were

generally manic and grotesque, Linder adopted the character of a svelte and handsome

young boulevardier, with sleek hair, trimmed moustache, and impeccably shiny silk hat

which survived all catastrophes. Max was resourceful and generally discovered some

ingenious way out of the many scrapes in which he found himself, usually as a result of

his incorrigible gallantry to pretty ladies. Linder perceived the comedy in the contrast

between Max's debonair elegance and the ludicrous or humiliating adventures which

befell him.Despite his stage training Linder was acutely conscious of the specific nature

of the cinema, recognizing the possibility it provided for subtlety of expression. He had

the gift of naturalness. Every action was in essence true to life. We laugh at his

predicaments because we know just how he feels.Inexhaustibly inventive, Linder had a

talent for devising endless variations upon some basic theme. In the sublime Max prend

un bain ( 1910), he apparently simple process of taking a bath brings problems that

escalate until Max, still in his bath, is carried through the streets shoulder high by a

solemn cortège of policemen. With exquisite sang-froid Max leans out and proffers his

hand to two passing ladies of his acquaintance.Max reached the peak of his popularity in

the years just preceding the First World War, when his international tours to make

personal appearances became royal progresses. His health was permanently impaired by

grave injuries he received fighting at the front during the war. He accepted a contract

from the Essanay Company to go to America to replace Chaplin. The failure of his films

there (largely due to Essanay's ugly attempts to use him to denigrate Chaplin, with whom

he was personally friendly) was a further blow to his spirits.Encouraged by Chaplin he

returned to America in 1921, and made three features which remain his masterpieces:

Seven Years' Bad Luck ( 1921), Be my Wife ( 1921), and a genial parody of Douglas

Fairbanks's The Three Musketeers, The Three Must-Get-Theres ( 1922). When these films

too were coolly received. Max returned to France only to find his reputation even there

eclipsed by Chaplin. He fell victime to the comedian's traditional melancholia.Despite this

he continued to work. He made an eerie horror-comedy, Au secours! ( 1923) with Abel

Gance, and went to Vienna to shoot Le Roi du cirque ( 1924). His comic brilliance was

undiminished, but his life was rapidly moving into tragedy.In 1922 he had become

infatuated with a 17 year old, Ninette Peters, whom he eventually married. Gravely

disturbed, With periods in a sanatorium, Max became prey to a pathological jealousy. He

and Ninette were both found dead in a hotel room on the morning of 1 November 1925.

His daughter Maud Linder concludes that he persuaded Ninette to take a soporific, and

then cut her veins and his own.DAVID ROBINSON

SELECT FILMOGRAPHY

La Première Sortie d'un collégien ( 1905); Les Débuts d'un patineur ( 1907); Max prend

un bain ( 1910): Les Débuts du Max au cinéma ( 1910); Max victime de quinquina(

1911); Max veut faire du théâtre ( 1911); Max professeur du tango ( 1912); Max toréador

( 1912); Max pédicure ( 1914); Le Petit Café ( 1919); Au secours! ( 1923) in USA Max in

a Taxi ( 1917); Be my Wife ( 1921); Seven Years Bad Luck ( 1921); The Three must-Get-

theres ( 1922)

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Linder, Maud ( 1992), Les Dieux du cinéma muet: Max Linder.

Mitry, Jean ( 1966), Max Linder.

Robinson, David ( 1969), The Great Funnies: A History of Film Comedy.

Italy: Spectacle and Melodrama

PAOLO CHERCHI USAI

Film production in Italy began relatively late in comparison with other European nations.

The first fiction film -- La presa di Roma, 20 settembre 1870 (The capture of Rome, 20

September 1870'), by Filoteo Alberini-appeared in 1905, by which time France, Germany,

Britain, and Denmark already had in place well developed production infrastructures.

After 1905, however, the rate of production increased dramatically in Italy, so that for the

four years preceding the First World War it took its place as one of the major powers in

world cinema. In the period 1905-31 almost 10,000 films -- of which roughly 1,500 have

survived-were distributed by more than 500 production companies. And whilst it is true

that the majority of these companies had very brief life-spans, and that almost all

entrepreneurial power was concentrated in the hands of perhaps a dozen firms, the figures

nevertheless give a clear indication of the boom in this field in a country which, though

densely populated (almost 33 million in 1901), lagged behind the rest of Europe in terms

of economic development.

The history of early film production in Italy can be divided into two periods: a decade of

expansion ( 1903-14) during which up to two-thirds of the total number of films in the

silent era were made, followed by fifteen years of gradual decline after the sudden

collapse in output, in common with the whole of Europe, during the war. In 1912 an

average of three films a day were released (1,127 in total, admittedly many of them

short); in 1931 only two feature films in the entire year.

BEGINNINGS

The tradition of visual spectacle has deep historical roots in Italy. Aspects of it which are

particularly important to the prehistory of cinema include entertainments in travelling