The Other Slavery (25 page)

Authors: Andrés Reséndez

Sometime in late July or early August, the plotters made their final preparations. Po’pay dispatched runners to dozens of Indian communities. Word traveled on their feet. These runners, keepers of accurate

information and athletes of astonishing endurance, ran in the summer heat, pushing as far south as Isleta and as far west as Acoma and the distant mesas of the Hopis. In pairs they snaked through canyons and skirted mountains, trying to remain inconspicuous as they covered hundreds of miles with ruthless efficiency. They were sworn to absolute secrecy. And even though they would convey an oral message, they also carried an extraordinary device: a cord of yucca fiber tied with as many knots as there were days before the insurrection. “[Each pueblo] was to untie one knot to symbolize its acceptance,” observed one medicine man from San Felipe who was implicated in the plot, “and also to be aware of how many knots were left.” The countdown had begun.

6

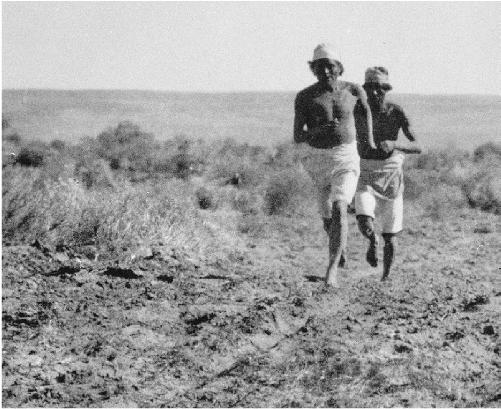

The tradition of Pueblo running has continued through the centuries. Here two runners compete in the Hopi Basket Dance races in 1919.

In early August, as the knotted cord traveled through the Pueblo lands, the first signs of dissension appeared. Po’pay had failed to notify

the Piros, the southernmost pueblos, of the plan, probably anticipating that they would not agree to participate. Worse, as the day of the uprising approached, some pueblos around Santa Fe refused to go through with the plot. They had initially supported the plan even though they would bear the brunt of the fighting against the Spaniards residing in the capital city. But during the waxing moon, they began to reconsider the grave consequences of an all-out war against a foe that possessed firearms and horses. With the moon nearly full and only two knots left in the cord, the Native governors of Tanos, San Marcos, and Ciénega fatefully decided to switch sides. They journeyed to Santa Fe to denounce the conspiracy and, in a more personal and insidious betrayal, alert the Spanish authorities to the whereabouts of two Indian runners, Nicolás Catúa and Pedro Omtuá, who were still making the rounds with the knotted cord.

Uncharacteristically, the Spanish governor and captain general of New Mexico, Antonio de Otermín, sprang into action. Since he had arrived in New Mexico two years earlier, Governor Otermín had permitted a clique of influential locals to run the province in his name. He could not be bothered with the drudgery of government. Instead, he pursued his own economic interests with abandon, granting a free hand to his

maestre de campo

(chief of staff), a wily New Mexican named Francisco Xavier. On August 9, however, upon receiving word of the Pueblo conspiracy, Otermín and his inner circle came alive.

7

The governor first ordered a detachment to intercept the two runners. Catúa and Omtuá were brought to him and confirmed that all the pueblos would revolt. Otermín and his close advisers sent warnings to the nearby towns, and the governor took steps to protect Santa Fe. He distributed firearms to the residents, posted soldiers in the main church to prevent its desecration, and made preparations in the casas reales to withstand a siege.

After learning that their plan had been discovered, however, the Indian leaders shrewdly moved up the date of the rebellion to the next day, August 10. Runners were probably sent out again to deliver a most urgent message: strike now.

Extraordinary Days

The revolt swept throughout the kingdom of New Mexico on August 10–11, destroying houses, ranches, and churches and killing some four hundred men, women, and children, or about twenty percent of New Mexico’s Spanish population. The rebels did not engage in wanton destruction or indiscriminate killing. Po’pay and the other leaders gave them clear instructions. They were to destroy missions, churches, and all manner of Christian paraphernalia: “break up and burn the images of the holy Christ, the Virgin Mary, and the other saints, the crosses, and everything pertaining to Christianity.” To wash away Christian baptisms, they were urged to “plunge into the rivers and wash themselves with amole, which is a root native to the country, washing even their clothing.” And to unmake their Christian marriages, the revolting Indians were to “separate from the wives whom God had given them in marriage and take whom they desired.” By many accounts, the rebels did as they were told. In the pueblo of Santo Domingo, a group of Indians descended on the church, killed the three missionaries, and dumped their bodies in the nave. In the pueblo of Sandia, farther south, the rebels destroyed the choir stalls, defecated on the main altar, and sacked all the paintings and religious objects in the church and the sacristy. They left a statue of Saint Francis but chopped off his arms with an ax. They also flogged a large statue of Jesus Christ on the cross.

8

The rebels also targeted priests and friars. Twenty-one out of thirty-three Franciscans, or about two-thirds of all the friars living in New Mexico, were killed. Those living in outlying communities were the most vulnerable. In Jemez, for example, a throng of Indians surprised Fray Juan de Jesús in the middle of the night. They took him out to the cemetery, which had been lit with many candles, stripped him, and forced him to ride a pig while they beat and mocked him. Then Fray Juan himself was made to get down on all fours, and the assailants took turns riding and whipping him. After the friar had been thoroughly humiliated and could no longer move, the Indians killed him by striking him with war clubs.

9

Similar fates awaited the missionaries living in the Hopi pueblos of present-day Arizona. At Oraibi, the attackers surrounded the friary in the wee hours of the morning. They broke down the door, to find the room’s only occupant—and possibly the only Spaniard living at Oraibi at the time—huddled in a corner. The Hopis promptly slashed the friar’s throat, extracted his heart, and dumped his body down the mesa. In nearby Shungopovi, Fray Joseph de Trujillo did not give up without a fight. After exchanging angry words with many Natives surrounding his house, he grabbed a sword and cut down the first Indian who broke in. The embattled friar was then surrounded and disarmed. He spent his last moments dangling over a fire, his hands tied behind his back, until his body was burned completely. Fray Trujillo was a veteran missionary who had served in the Philippines and New Mexico, two of the most exposed frontiers in the Spanish empire, and had repeatedly expressed his desire to become a martyr. In the summer of 1680, he finally succeeded.

10

Religion was clearly a flashpoint of the conflict. Throughout the seventeenth century, missionaries had made every effort to suppress “idolatry” and “superstition” and to subdue the Native medicine men, who had become their main competitors and antagonists. For their part, the medicine men had retained their traditional beliefs and clandestinely practiced their religion inside kivas. When Po’pay descended victorious from his perch in Taos and toured the pueblos, he commanded the Indians to return to their old traditions and beliefs, declaring that Jesus Christ and the Virgin Mary had died.

11

Yet earthly reasons also impelled the rebels to strike at the Spaniards, as the unfolding of the conflict makes abundantly clear. Even as the Indians attacked churches, missions, and remote ranches, Santa Fe remained unconquered. Slowly rebels began massing on the outskirts of the Spanish city. Within a week, some five hundred warriors from the pueblos of Pecos, Galisteo, San Cristóbal, San Lázaro, San Marcos, and Ciénega gathered less than three miles to the south of the central plaza. Armed with bows and arrows and stones, they began advancing, while burning cornfields and looting the outlying houses. The rebels

made it known that “they were coming to kill the governor and all the Spaniards.”

12

Since the start of the rebellion, the Spanish residents of Santa Fe had congregated in the casas reales in the central plaza. In the seventeenth century, the plaza of Santa Fe, an unkempt swampy area shaded by large trees, was roughly twice as large as it is today. Somewhere in this large quadrangle (archaeologists do not know exactly where) stood the Spanish stronghold. It was not a spacious building. Thus the atmosphere must have been infernal as a thousand refugees huddled together in anticipation of the attack, crowding every room while improvising beds, latrines, and cooking areas. Despite the continuous wailing of children and women, the “war whoops” from the outside were audible.

13

On the morning of August 15, five days into the rebellion, an Indian fully decked out for war rode into the plaza and stopped in front of the casas reales. Indians were barred from riding horses and bearing arms, yet this man had arrived on a horse, wearing a protective leather jacket, and carrying a harquebus, a sword, and a dagger—all Spanish weapons. As a further provocation, he wore a sash of red taffeta that had been looted from the church in Galisteo. Governor Otermín and some of his soldiers recognized the rider as a Pueblo chief who spoke Spanish and was known among the colonists as Juan. The governor came out of the building for a parley. It was only then that Otermín finally heard what the rebels wanted. Juan requested that “all classes of Indians held by the Spanish be given back.” He also demanded “that his wife and children be given up to him” and that “all the Apache men and women whom the Spaniards had captured in war be turned over to them, inasmuch as some Apaches who were among them were asking for them.”

14

Governor Otermín, who had been in New Mexico for two and a half years, must have heard Juan’s demands with trepidation. Like his predecessors, Otermín had been involved in the traffic of Indians. The antislavery crusade of the early 1670s had temporarily reduced the number of New Mexican Indians exported to the silver mines. But the slave trade had bounced back later in the decade, and Otermín had been a major reason for this resurgence. In 1678 and 1679, the new governor had dispatched slave-bearing caravans from New Mexico and offered safe

passage to other traffickers, “inviting everyone to go together in a convoy,” as one witness put it. Although it is tempting to portray Otermín as a grasping, covetous governor, in reality he was no worse than other seventeenth-century governors throughout the Spanish colonies, all of whom had to purchase their offices from the crown. Not only did they have to finance their positions up front, but they also had to be content with only half their yearly salary, as the crown kept the other half in the form of a special tax called the

media anata.

To recoup their considerable investments, governors had little choice but to aggressively pursue all economic opportunities within their jurisdictions, including the trafficking of Indians.

15

Otermín was still an outsider governor with little knowledge of the kingdom that he was supposed to rule. After the parley, he must have gone back inside the casas reales to discuss the rebels’ demands with his closest collaborators, including his

maestre de campo,

Francisco Xavier, “to whom the governor had granted all of his authority and power.” It was Xavier who may well have introduced Otermín to the slave trade and acted as his partner. Sources describe Xavier as “a man of bad faith, avaricious, and sly,” who had driven the Indians of New Mexico “to the ultimate exasperation.” When the rebels had surrounded the Spanish stronghold, they had reportedly shouted, “Give us Francisco Xavier, for whom we have revolted, and we will return to peace as before.”

16

Xavier evinced a rare combination of religious intolerance and ruthless ambition. His zealotry was not new. Nearly twenty years earlier, he had started complaining about the kachina dances performed by the Indians of Isleta, San Ildefonso, and other pueblos. Even though colonial authorities had authorized the dances, Xavier remained adamant that they were inspired by the Devil. On that occasion, his misgivings had little effect. But fourteen years later, after Xavier had ascended to secretary of New Mexico, he was able to act on his strict religious sensibilities. He presided over the infamous 1675 campaign against “Indian sorcerers and idolaters” and the roundup of Po’pay and forty-six other medicine men. He personally oversaw their trials and punishments. Unquestionably, Po’pay regarded Xavier as his personal enemy.

17

As a long-standing and notorious participant in the Indian slave

trade, Xavier had made other Indian enemies, particularly among the Apaches. Xavier’s signature appears on a 1666 receipt that required him to furnish “two Christian boys of the Apache nation, one of them ten years old and named Baltazar, and the other eight or nine and named Andrés,” to Governor Fernando de Villanueva (1665–1668). Shortly before the outbreak of the Pueblo Revolt of 1680, he had welcomed a group of Apaches who had arrived in the pueblo of Pecos to trade. (Pecos had long been a trading post linking the Plains Indians living to the northwest and Spanish New Mexico.) The unsuspecting Apaches entered the pueblo ready to do business, but in spite of numerous assurances, Spanish soldiers promptly imprisoned them on Xavier’s orders. He distributed some of the Apaches in Pecos and sent most of them to Parral to be sold as slaves. It is likely that these were the Apaches whom Chief Juan requested from Governor Otermín during their parley.

18