The Other Slavery (24 page)

Authors: Andrés Reséndez

In the end, the Audiencia of Manila rescinded the king’s emancipation decree on September 7, 1682, and replaced it with a new decree: all previously liberated slaves had to return to their duties within fifteen days upon penalty of one hundred lashes and one year in the galleys (forced service as a rower aboard a galley, or ship). Charles II continued to press his case for liberation, but ending formal slavery in the Philippines proved very difficult.

39

The Spanish campaign washed over the frontiers of the empire in the closing decades of the seventeenth century. But it followed such different trajectories that assessing its overall impact is as daunting as were the goals of the campaign itself. Most tangibly, it brought freedom to a few thousand Native slaves out of some three to six hundred thousand. In Trinidad, northern Mexico, and even Chile and the Philippines, slave owners felt compelled to free some of their slaves. Yet these freedmen constituted but a fraction of the total number of Native slaves in the empire. The crusade thus brought into sharp relief the limits of monarchical power, especially in distant lands and backwaters.

The crusade also had a chilling effect on European slavers. For all of his reluctance to free the slaves, Governor Enríquez of Chile did issue orders prohibiting soldiers from launching slave raids and taking Indian captives after 1676. In the Philippines, where the proslavery coalition had proved much too strong and had defied royal orders, the Audiencia of Manila nonetheless agreed to suspend for a period of ten years the enslavement of Filipino Natives who were in the habit of hiding from Spanish authorities. The monarchy’s newfound determination to prosecute and punish slavers surely made their work much riskier.

40

The Spanish campaign also pushed the slave trade further into the hands of Native intermediaries and traffickers, whether in northern Mexico, Chile, or the llanos of Colombia and Venezuela. The crown had some power over Spanish slavers and authorities, but its control over indigenous slavers was extremely tenuous or nonexistent. The late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries witnessed the emergence of

powerful indigenous polities that gained control of the trade. The Carib Indians consolidated their position in the llanos as the preeminent suppliers of slaves to French, English, and Dutch colonists, consistently delivering hundreds of slaves every year. In the far north of Mexico, the Comanche Indians came to play a similar role and began a breathtaking period of empire building.

Another unanticipated result of the antislavery crusade was that it raised the expectations of Indians throughout the empire, which in the vast majority of cases remained unmet. Their experience of the campaign was marked by dashed hopes, anxiety, and restlessness. In some instances, uncertainty and turmoil culminated in major insurrections, as in the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 in New Mexico.

Although the Spanish campaign often fell short of its stated goals, it foreshadowed future abolitionist movements. In 1833 Great Britain emancipated nearly eight hundred thousand colonial slaves, but emancipation was gradual and equivocal. The “freed” slaves were first subjected to an unpaid “apprenticeship,” which gave owners “slavelike” labor for a period of time. Twenty-five years after the launching of the British experiment, many believed that the former slaves were worse off than before. Similarly, at the conclusion of the American Civil War, Congress passed the Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, granting freedom to all slaves within the nation. The subsequent decades, however, witnessed the rise of draconian codes in some states aimed at restricting the rights of African Americans, as well as the enforcement of labor practices that amounted to involuntary servitude. As with the Spanish campaign, these grand emancipation declarations delivered less than they promised.

Yet the alchemical ingredients of emancipation were in the air during the closing decades of the seventeenth century. Right at the time when the Spanish campaign was gaining momentum in 1671–1672, the lord proprietors of the English Carolina colony ordered that “no Indian upon any occasion or pretense whatsoever is to be made a Slave, or without his own consent be carried out of Carolina.” It is unclear whether the proprietors derived some inspiration from the Spanish monarchs, but their pronouncement shows that the idea of Indian emancipation was

circulating widely in the Americas. Other precocious abolitionists of the era included Francis Daniel Pastorius, a Quaker from Germantown, Pennsylvania. Based on the biblical admonition “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you,” Pastorius protested against African slavery in 1688 and urged his contemporaries to avoid discriminating against others, making “no difference of what generation, descent, or Color they are.” In 1700 Samuel Sewall, a Boston judge, published an antislavery tract that offered incisive rebuttals of the main arguments traditionally used to justify the enslavement of Africans. Epifanio de Moirans, a French Capuchin missionary living in Havana, probably came closest than anyone else in the seventeenth century to understanding that Indian slavery and African slavery were two sides of the same coin. Europeans “seize the lands of the natives of the Indies once they have killed them or enslaved them,” he wrote in

A Just Defense of the Natural Freedom of Slaves

in 1682, “and they also expel the Blacks from their own lands and reduce them to the perpetual slavery of someone shipped to America or transported to Europe.”

41

6

The Greatest Insurrection Against the Other Slavery

I

N THE SPRING

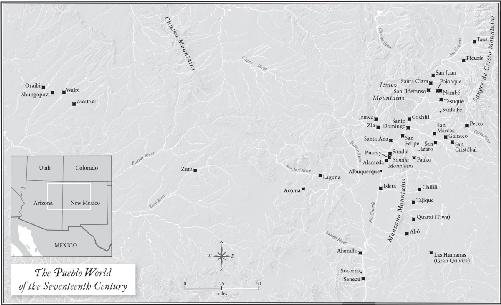

of 1680, the Pueblo Indians of New Mexico devised an audacious plan of liberation. The Pueblo world consisted of some seventy settled, self-contained communities scattered throughout the upper reaches of the Rio Grande and its tributaries. Each pueblo, the Indians secretly agreed, would rise up on the same day and kill its friars and civil authorities, burn down its churches, destroy its Christian images and rosaries, and unmake all Christian baptisms and marriages. In one decisive coup, these Indian villages would erase most traces of the Spanish presence. The Pueblos had by then coexisted with Europeans for eighty-two years, merely three generations. An Indian named Juan Unsuti, who must have been more than one hundred years of age at the time of the insurrection, still recalled “as though it were yesterday when the Spaniards had entered this kingdom.” He remembered life before the white intruders and believed, along with many other Natives, that this earlier way of life could be retrieved.

1

The rebels’ greatest strategic insight was that all or nearly all the pueblos should act simultaneously. If they could marshal their vast numerical superiority, they could dislodge the Spaniards swiftly. In 1680 there were about two thousand Spanish colonists scattered throughout New Mexico, perhaps three thousand if we include their indigenous and mestizo

dependents. Unlike other provinces with booming silver mines, New Mexico remained a backwater, unable to attract a significant Spanish presence. Those few settlers lived among seventeen thousand Pueblo Indians—thousands more if we include the Apaches, Utes, Navajos, Mansos, and others. In some outlying pueblos, such as the Hopi villages of what is now northeastern Arizona, the European presence was limited to the bare minimum: two Franciscan friars at Oraibi, one at Shungopovi, and one at Awatovi. Killing these isolated friars and destroying their temples could be accomplished with ease. Other pueblos along the Rio Grande had a sprinkling of Spanish families in addition to the local friar. Subduing these settlers would be only marginally more difficult. The greatest resistance could be expected in Río Abajo, around the southern pueblos of Isleta, Alameda, and Sandia—where the Spanish population density was higher—and above all in the Spanish city of Santa Fe, where a thousand Europeans and their dependents resided. As the seat of government, Santa Fe also boasted the

casas reales,

a sturdy building capable of withstanding a siege. But even here, the Spaniards were outnumbered by the surrounding Indians of the Galisteo Basin.

The plan was brilliant, but it hinged on getting the villages to act together while also maintaining secrecy. Taos, the cradle of the plot, lay at the northeastern edge of the Pueblo world. It was 70 miles from Taos to the city of Santa Fe, almost three times the length of a marathon. Messengers on foot would require an entire day and a grueling effort to cover that distance. And Santa Fe was just the start. To communicate with the southern pueblo of Isleta, the couriers would have to run 140 miles, or the equivalent of five marathons; to get to the mesa-top pueblo of Acoma, they would have to journey 180 miles, or almost seven marathons; and to reach the Hopi pueblos, they would have to cover upwards of 300 miles, or twelve marathons. Distance mattered greatly when success depended on dozens of Indian communities rising up on the same day. If some pueblos could not be notified in time or acted too early or too late, the insurrection could easily turn into a prolonged and debilitating war against the Spanish.

Even more challenging than geography were the cultural differences. Although the Spaniards used the generic term

pueblos

to refer

to all of these compact Native communities, in fact they spoke different languages and possessed different traditions and beliefs. Several of the pueblos spoke related languages of the Tanoan linguistic family, but interspersed among them were villages that spoke Keresan languages such as Cochiti, San Felipe, Zia, and Acoma. Yet other pueblos spoke languages completely unrelated to either the Tanoan or Keresan families, among them Zuni and Hopi. As they plotted the insurrection, the leaders had to bridge ancient linguistic and cultural divisions. Ironically, Spanish already served as a lingua franca and probably facilitated the anti-Spanish conspiracy.

The most formidable obstacle was neither geographic nor cultural but political. The plotters had to secure the participation of each pueblo individually, as there was no political unit larger than the notoriously autonomous village. The Pueblo Indians had wanted to shake off Spanish rule for thirty years, but every time they tried, they either failed to persuade a sufficient number of pueblos or their plans had been revealed. In 1650 the Spaniards had learned about a plan to “destroy the whole kingdom,” which had led to nine Native leaders being hanged and to many others being sold as slaves for ten years. A few years later, the ever restless pueblo of Taos had “dispatched two deerskins with some pictures on them signifying conspiracy after their manner,” but the plan had been abandoned due to the refusal of some pueblos. In 1665 New Mexico’s governor, Fernando de Villanueva, had learned of yet another conspiracy and had some rebels “hanged and burned in the Pueblo of Senecú as traitors and sorcerers.” The projected revolt of 1680 was just the latest incarnation of a plan that had been long in the making—and had failed on every previous attempt.

2

Undaunted, Pueblo leaders gathered during the spring and summer inside underground ceremonial centers, or kivas, where no whites were allowed. Several leaders were involved in the plot, but a fifty-year-old Indian named Po’pay became the most visible head of the movement. He spoke “with a voice that carried above all others,” as one witness later recalled. Many Natives believed he was in contact with Poseyemu, a culture hero recognized by all the pueblos and whom the Spaniards believed to be the Devil.

3

Once the conspiracy got under way, Po’pay would stop at nothing to see the revolt through. He killed his own son-in-law to prevent word of the plot from leaking out. The murder occurred in Po’pay’s house—quite likely at his own hands. His unshakable resolve carried a history. Five years earlier, the governor of New Mexico, General Juan Francisco Treviño, had launched a campaign against Native “sorcerers and idolaters.” On charges that they had bewitched a friar and some of his relatives at the pueblo of San Ildefonso, forty-seven shamans, including Po’pay, were rounded up and brought to Santa Fe. After an initial investigation, three prisoners were taken to the pueblos where they had allegedly used their supernatural powers—Nambé, San Felipe, and Jemez—and hanged. A fourth committed suicide before his execution. Among the rest, the luckier ones received lashings or were sold into slavery. After a fierce flogging, Po’pay was released. He returned to his native pueblo of San Juan, where he stayed for some time. In the face of more threats, he retired to distant Taos, where he bided his time and planned his revenge.

4

Po’pay and the other plotters set the date of the uprising for the full moon of August, after the corn had ripened. Since the leaders were medicine men—

hechiceros

(sorcerers) in the damning parlance of Spanish authorities—they used a network of medicine societies to negotiate and forge alliances. Each pueblo possessed a medicine association or society that structured the town’s ceremonial life. Only members of this society could take part in its gatherings and rites, although visiting medicine men from other pueblos were welcome. Through the spring and summer of 1680, medicine associations all across the Pueblo world prepared quietly for the insurrection. Young Pueblo Indians captured by the Spaniards during the rebellion claimed that they knew little about the conspiracy but that “among the old men many juntas had been held with the Indians of San Juan, Santa Clara, Nambé, Pojoaque, Jémez, and other nations.” In fact, these “old men” were by and large the only ones who knew the details of the plan. Most of the others had only an inkling of the revolutionary changes about to occur.

5