The Other Slavery (21 page)

Authors: Andrés Reséndez

Philip IV was a great patron of the arts. Numerous paintings now in the Museo Nacional del Prado in Madrid were acquired, received as gifts, or commissioned by him. His favorite painter was Diego Velázquez, who made several portraits of the king, including this one in 1623–1624.

These escapades also afforded Philip IV the opportunity to indulge his other great passion: women. At the Corral de la Cruz, he became smitten with a sixteen-year-old actress named María Inés Calderón, who took Madrid by storm with her sweet voice and captivating manner. After one of her performances, the king invited her to join him in his apartment, which caused the king’s passion to grow even wilder. Thus began an intense but short-lived relationship. Philip had a son with María Inés and would go on to father

more than twenty illegitimate children with as many women.

3

Philip was not, however, just a pleasure seeker. Almost incongruously, he was also extremely religious. When in his thirties, he suffered a personal crisis that steered him toward mysticism. As a result, he sacked the man he had relied on to rule his enormous empire for more than twenty years, the Count-Duke of Olivares, and announced that he would henceforth govern using no intermediaries.

“Yo tomo el remo”

(I take over the oar), he wrote to one of his governors. Philip summoned mystics from across Christendom so that he might “rule and govern in harmony with their revelations.” During this critical time, he met Sor María de Ágreda, an abbess from Old Castile who was regarded as the preeminent mystic of her time. After a brief encounter, the two struck up an extraordinarily candid correspondence that would last for twenty-two years, until the end of their lives in 1665. Through the more than six hundred letters they exchanged, it is possible to peer into Philip’s soul.

4

Philip IV believed that God followed his every move and rewarded or punished the whole of the empire according to his conduct. He confided to Sor María that his sexual appetite was the cause of Spain’s misfortunes: “I scarcely have any trust left in myself, because I have sinned a great deal and I deserve the punishments and afflictions that I suffer, and the greatest gift I could receive is for God to punish me rather than these kingdoms, for I am the one to blame and not them who have always been true Catholics.” As the contrite Philip sought to rule in a way that would please God, Sor María urged him to dispense “true justice” and stamp out “vices and all manner of sin.”

5

Of the many matters that required Philip’s attention, the enslavement of Indians in the New World was decidedly secondary. We do not know what Philip’s personal views on the subject may have been, but during the early years of his reign he favored the iron fist. The kingdom of Chile, for instance, had experienced a massive Indian insurrection at the close of the sixteenth century. The situation had been so critical that Philip’s father and predecessor, Philip III, had taken the drastic step of stripping the Mapuche Indians of the customary royal protection against enslavement in 1608, thus making Chile one of the few parts of the empire where slave taking was entirely legal. Philip IV inherited this morass when he ascended to the throne and could have done something to improve relations. Instead, in 1625, four years into his reign, the young monarch not only endorsed his father’s policies but made them even harsher by ordering “an offensive war in the same way that it used

to be waged before the King our lord and my father (may his soul rest in peace) stopped it and made it defensive only. And in particular you will make sure that all Indians captured in the war will be distributed as slaves.” Under Philip’s pointed directions, the traffic of Indians flourished in Chile for decades.

6

Yet in the twilight of his life, Philip came to grips with the failure of his policies as he struggled to save his soul. In 1655, after thirty years of insurrection, the Mapuches launched yet another attack, making clear that the conflict was not close to an end. Philip’s offensive war had produced not a Spanish victory and a durable peace but a perpetual state of warfare kept going by slave takers and owners of Indian slaves, who were its chief beneficiaries. So the monarch and his ministers changed course. The crown’s policies toward the Natives of Chile became markedly softer. In 1656 Philip issued a strongly worded order prohibiting the so-called

esclavitud de la usanza,

or customary slavery, in which Natives willingly sold family members; in 1660 he curtailed textile sweatshops, which were notorious for using Indian slaves; and in 1662 he issued no less than three royal orders forbidding the trafficking of Chilean Indians into Peru. That same year, Philip requested a reassessment of the imperial policies in Chile and expressed his belief that slave taking had become the main obstacle to peace with the Mapuche Indians. Philip’s opinion had changed much since the confident years of his youth. Yet the king died before he could set the Indians of Chile free and discharge his royal conscience.

7

But Philip was not alone in trying to make things right. His wife, Mariana, was thirty years younger than he, every bit as pious, and far more determined. The crusade to free the Indians of Chile, and those in the empire at large, gained momentum during Queen Mariana’s regency, from 1665 to 1675, and culminated in the reign of her son Charles II. Alarmed by reports of large slaving grounds on the periphery of the Spanish empire, they used the power of an absolute monarchy to bring about the immediate liberation of all indigenous slaves. Mother and son took on deeply entrenched slaving interests, deprived the empire of much-needed revenue, and risked the very stability of distant provinces

to advance their humanitarian agenda. They waged a war against Indian bondage that raged as far as the islands of the Philippines, the forests of Chile, the

llanos

(grasslands) of Colombia and Venezuela, and the deserts of Chihuahua and New Mexico. And yet both were exceedingly unlikely emancipators.

Mariana was an Austrian by birth who had arrived in Spain when she was fifteen years old to be betrothed to the aging Philip. Because she was originally a foreigner and a great deal younger than her late husband, some authors have depicted Queen Mariana as a weak ruler operating in a world of influential men. The facts run contrary to this view, however, as she was notoriously strong willed. As one scholar of the Spanish court put it, “Her commendable fixity of ideas sometimes degenerated into obstinacy and her laudable code of conduct into stubbornness.” If anything, she could be faulted for attempting to extend her power beyond her regency and into her son’s reign.

8

King Charles II was an even more improbable champion of Indian rights. Carlos was only three when his father, Philip IV, died, and already showing signs that something was wrong with him. “He seems extremely weak, with pale cheeks and very open mouth, a symptom, according to the unanimous opinion of the doctors, of some gastric upset,” wrote a French diplomat, “and though they say he walks on his own feet and that the cords with which the Menina [maid] guides him are simply in case he makes a false step, I doubt it, since I saw him take his nurse’s hand to hold himself up when they retired.” Carlos grew to be a listless adolescent. He walked slowly alongside walls or tables to steady himself and showed little interest in his surroundings. Few believed that he possessed an independent will. His physical and mental traits led his subjects to refer to him as “el Hechizado” (the Bewitched).

9

The many orders and decrees that have come down to us illuminate Queen Mariana’s and then King Charles’s determination to protect the Indians. They speak of the “gravity of the matter of Indian slavery” and “the scruples of conscience that their enslavement causes.” Mariana often referred back to Philip’s precedents, revealing a widow’s desire to bring to fruition a project cut short by death. Something similar is true

of Charles. In his most important decree, freeing all the slaves of the American continent, he devoted admiring words to his mother’s efforts. Theirs was a family enterprise passed from one member to the next.

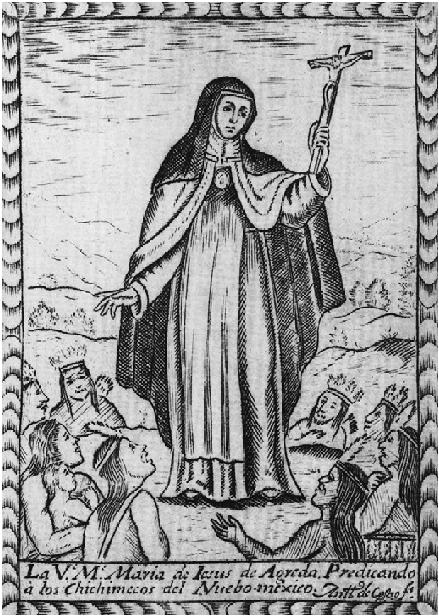

More than a century after Sor María’s reported apparitions in northern Mexico, her memory lived on. This 1730 woodcut shows the “lady in blue” spreading the Gospel among nomadic Indians in New Mexico.

Perhaps the great mystic of Ágreda lurked behind their family’s resolve. Philip became deeply impressed by Sor María’s earnest injunctions to rule in a Christian spirit by fighting oppression and providing justice, notions that extended so naturally to his indigenous subjects. Moreover, there had been an episode in Sor María’s past that connected her directly to the Indians. Back in the early 1620s, when Philip was busy prosecuting the war against the Indians of Chile, Sor María was gaining renown for her trances. During these spells, and without ever leaving her room in Ágreda, she traveled to the Americas. Cloaked in blue, she also appeared to the Indians of New Mexico and Texas, preaching the Gospel and urging them to accept the holy water of baptism. Sor María

herself could not tell whether she had actually bilocated—that is, had been in Europe and America at the same time—or, as she would later be more inclined to think, it had been “an angel in my shape that appeared there and preached and taught them, and over here the Lord showed me what was happening.” But the fact was that many Natives of New Mexico had witnessed multiple apparitions of a white nun. Friars reported meeting Indians who had never been in contact with the Spanish but already knew the rudiments of the Catholic faith. When asked how they knew, they had simply replied, “The lady in blue.” This is how Sor María first came to Philip’s attention and how their paths began to converge.

10

In their correspondence, neither Sor María nor Philip wrote a single word about this episode. It was just too sensitive a subject, and the letters could fall into the wrong hands. At least on two occasions, the Inquisition investigated the nun’s claims, and Philip probably used his influence to protect her. Yet Sor María’s unique connection to the New World and its peoples must have impressed not only Philip but his successors as well. Queen Mariana corresponded with the mystic of Ágreda, and after María’s death in 1665, Mariana supported her canonization. Charles II was no less devoted. In 1677, during the thick of his antislavery campaign, he made a point of visiting Ágreda to honor Sor María’s legacy and perhaps to gain some strength and guidance for the difficult road ahead.

11

An Empire of Slaves

The Spanish antislavery crusade generated letters, testimonies, and reports about the slaving grounds of the empire: twelve hundred pages of campaign-related documents for northern Mexico, one thousand for the Philippines, three hundred for southern Chile, and decreasing amounts for Argentina, the coasts of Colombia and Venezuela, and other places. The source of these documents reveals a great deal about the geography of Native bondage. In the early days of conquest, European slavers were attracted to some of the most heavily populated areas of the New World, including the large Caribbean islands, Guatemala, and central

Mexico. But by the time the antislavery crusade got under way in the 1660s, nearly two centuries after the discovery of America, the slaving grounds had shifted to remote frontiers where there were much lower population densities but where imperial control remained minimal or nonexistent and the constant wars yielded steady streams of captives.

12

Five major slaving grounds are evident in the documentation of the antislavery crusade of the seventeenth century. The most daunting and morally fraught was in Chile, where slave taking had remained legal between 1608 and 1674. With the crown’s explicit permission, slavery had flourished there. A Spanish chaplain who had lived in Chile for thirty years (fifteen of those among the Mapuche Indians) penned a clear-eyed report for Queen Mariana describing how Spanish captains lured the Indians with false promises of friendship, asking them to come to an appointed place with their families and animals. In some instances, the Indians were in the process of preparing a meal to celebrate and formalize their alliance with the Europeans when they were mercilessly attacked and taken prisoner. These were not vague accusations but precise reports including names and numbers: “The cacique Catilab was killed with spears and they took 17 captives from him”; or “The cacique Ancayeco fell dead there, and he had brought 12 family members with him and they took all of them.” By the chaplain’s count, one raid in 1672 netted 87 captives and another 274. In previous years, he had reported slaving raids resulting in 300 to 400 captives, “and I could describe many other unjust raids and abusive deaths in the past.” Governor Juan Enríquez affirmed categorically in 1676 that “in Chile there are many more Indian slaves than Spaniards,” an estimate that even if halfway accurate would put their number in the tens of thousands. Slaves were so plentiful that merchants also shipped them to Peru, where cities and mines were perennially in short supply of laborers. Indians branded on the face arrived “in great numbers” at the port of Callao, the gateway to Lima, “where they were all thrown out onto the plaza and some were sold and others only shown.”

13