The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain (57 page)

Read The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain Online

Authors: Oppenheimer

Figure 11.5b

Intrusions from the traditional Anglo-Saxon homelands of Schleswig-Holstein (Angeln) and north-west Germany (Old Saxony). Only an average of 3.8% British male gene types have matches in the Anglo-Saxon homeland region. This rises to an average 5.5% in England and 9–15% in parts of Norfolk. Frisia has no similar degree of matching, indicating that the Anglo-Saxon gene flow event was real, but very modest.

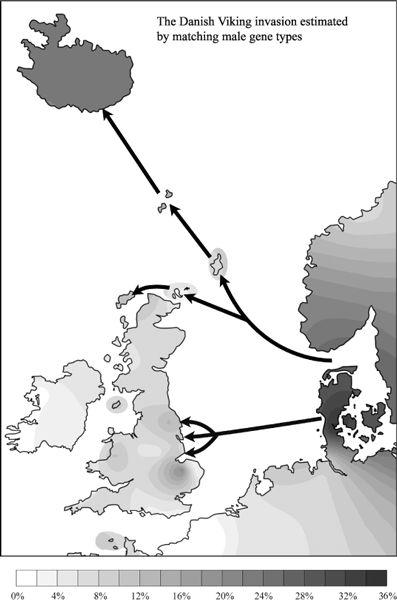

Figure 11.5c

Intrusions from Denmark. These matches are found in areas consistent with both Anglian and Danish Viking invasions (

Figures 9.2a

and

12.2

), namely the Fens (8%), Fakenham, Norfolk (19%) and York (11%), but also other areas consistent only with Vikings, for instance Iceland.

Figure 11.5

tells us a lot about specific gene type matches across the North Sea, but before describing the more interesting Anglo-Saxon stuff, I should mention several things which serve to validate the method. The most important source region for West European matches overall is, as expected, Iberia (

Figure 11.5a

). Even Trondheim in northern Norway has over 25% from the southern source. Ireland, coastal Wales, and central and west-coast Scotland are almost entirely made up from Iberian founders, while the rest of the non-English parts of the British Isles have similarly high rates. England has rather lower rates of Iberian types with marked heterogeneity, but no English sample has less than 58% of Iberian types, or what Capelli and colleagues might call ‘indigenous’ gene types. Looking at this picture the other way round, overall male intrusion from Northern Europe into England from any time since the last Ice Age varies from 15% to 42% (average 30%) in different samples. This conservative Atlantic coastal picture for the British Isles is completely consistent with the balance of sources of gene flow into the British Isles discussed earlier in this book.

How does my range of 15– 42% of intrusive North European male gene type markers to England compare with Capelli’s or Weale’s estimates? Although the dataset is nearly the same, the methods are different, so strict comparisons cannot be made. But my average figure of 30% is obviously closer to Capelli’s estimate of about 40% intrusion than to Weale’s 100% wipeout.

38

However, given that the cross-Channel matches inevitably include a much larger flow of founder gene types from the earlier Mesolithic and Neolithic periods, the overall figure of 30% invasion into England from Northern Europe since the Ice Age is still most likely to be a gross overestimate of the recent Anglo-Saxon invasion, and even more so when we focus just on matches with the ‘Anglo-Saxon homeland’.

When we do begin to look at the effects and variation in rates of specific ‘Anglo-Saxon’ gene types throughout Britain, several patterns emerge. First, the 30% intrusive figure falls sharply to 5.5% in England, and an average of 3.8% over all of the British Isles. This still seems to point to a real, though small, Anglo-Saxon invasion of eastern Britain and England (

Figure 11.5b

). Exact gene type matches from the putative Anglo-Saxon homelands are found at frequencies of 5–10% throughout England.

39

Within England the highest rates of intrusion, 9–15%, are seen in parts of Norfolk, in the Fen country around the Wash and, notably, in the Mercian and Anglian English towns of Weale’s transect (shown in

Figure 11.2a

).

My figure of 5.5% for genetic intrusion within England, rising to a maximum 9–15% in eastern England, can be compared

with archaeologists’ estimates of the ‘Anglo-Saxon’ invasion. Presently, the boldest of these, given by Reading University archaeologist Heinrich Härke, is of an invasion of about 250,000 people, into a British population of 1–2 million. Translated back into population proportions, in his own words:

Archaeological and skeletal data suggest an immigrant–native proportion of 1:3 to 1:5 in the Anglo-Saxon heartlands of southern and eastern England … but a much smaller proportion of Anglo-Saxons (1:10 or less) [in] south-west, northern and north-west England.

40

These burial-based figures of 10–33% immigration give a range about two to three times higher than mine, but still lower than Capelli or Weale’s genetic estimates.

Outside England, similar but slightly lower rates of intrusion are seen only in the Channel Islands, the Isle of Man, Cornwall and farther north on the east coast of Scotland and in Orkney and Shetland. Elsewhere outside England, ‘Anglo-Saxon’ intrusions are uniformly low, with Scotland at 1.7%, the Scottish Isles at 3%, Wales at 1.5% and Ireland at 0.8%. The exception to this picture is the Llanidloes sample (5.3%) which, we have seen elsewhere, always tends to group more with England and holds all the Welsh Anglo-Saxon matches (

Figure 11.5b

).

Curiously, however, the counties along the ‘Saxon coast’ of southern England have a consistently lower rate of ‘Anglo-Saxon’ matches than the Anglian regions: 5%, which is close to the baseline background level for the rest of England. This

lower ‘Anglo-Saxon’ signal for the English south coast is more consistent with Bede’s fifth-century invasion of Angles than with Gildas’ claimed dramatic

Adventus Saxonum

of the same date. Combined with genetic evidence for earlier Neolithic and Bronze Age intrusions into Wessex and the south coast (see

Chapter 5

), this would also be more consistent with a longer-term presence of north-west Europeans in the English Saxon counties.

Matched Danish gene types in the British Isles, although to some extent overlapping, also differ sharply from the ‘Anglo-Saxon’ ones in that they are found both within and outside England in a characteristic coastal distribution, geographically suggestive of historically recorded Viking raids (

Figure 11.5c

). Their different distribution but similar approximate dating suggests the Vikings as more likely culprits than Angles, and I shall return to this point later.

Perhaps the best validation of my matching approach to

specific

gene flow into Britain from southern Scandinavia and the Cimbrian Peninsula is the nearly complete absence from the British Isles of the numerous gene types specific to Frisia. Frisia is so much nearer geographically to eastern Britain, and so much closer in language and gene-group mix, that, on the basis of neighbourly affinities it would be expected to have more valid matches than the Cimbrian Peninsula – but it has virtually

none

. Needless to say, I have not shown the Frisian map for this non-migration.

Overall, 4% of Anglo-Saxon male intrusion into the British Isles (maximum 9–15% in those areas of eastern England which from the archaeology would have been expected to bear

the brunt) seems more reasonable than the wipeout theory. Assuming that it is a true reflection, 4% overall should still not be regarded as a minor event. That is a higher immigration figure than my estimate of 3% (see

Chapter 5

) for the entire Bronze and Iron Ages put together, and would represent ancestors for more than a couple of million of today’s population.

So far I have discussed only male markers in connection with the Anglo-Saxon invasions. This is mainly because that is where the most geographically specific, and indeed most of the published, genetic information is found. The mtDNA maternal evidence, such as it is, tends to support my story.

The Dark Age historians say rather little about women crossing from Europe, except for Procopius’ second-hand report in which he mentions annual cross-channel family holidays (see

Chapter 9

): ‘So great apparently is the multitude of these peoples that every year in large groups they migrate from there with their women and children and go to the Franks.’

41

Gildas’ report spoke only of warriors, although he is obviously talking about Saxons settling. We cannot, however, assume by default of accurate history that the

Adventus Saxonum

would have been purely a male elite, wherever it came from. Part of the independent body of evidence which suggests mass movement of peoples relates to the extensive contemporary flooding of the Continental coastline, leading to land hunger, particularly in Frisia.

As we have seen, some historians and archaeologists have seen these invasions as massive, with whole communities moving in from Germany and sweeping across a defenceless and largely depopulated England.

The English maternal genetic record in mtDNA undermines this story with complementary evidence from two key maternal lines (see also

Chapter 5

). One of these, J1a, specifically links Germanic speaking areas of Europe with England and is not found in other parts of the British Isles except for Lowland Scotland. Cambridge geneticist Peter Forster, however, argues that this line is most likely to have entered Britain in the Neolithic, not the Dark Ages.

42

Apart from the observation that the overall European expansion date for this line is around 5,000 years ago, Forster has what is perhaps a more telling piece of negative evidence: that English females have a low rate of a specific Saxon mtDNA marker.

43

Instead, their main cross-channel maternal links are considerably older. So, if only a few Saxon males came during the Dark Ages, they would have been matched by similarly few females.

In this chapter, I first presented three studies which used genetic similarity or distance between modern populations as means of addressing the question of Anglo-Saxon wipeout vs continuity theories. Their results were wildly at variance with one another and greatly overstated even the most aggressive modern archaeological view of that invasion. Apart from criticisms of their assumptions, and the lack of dating and resolution in their methods, my main worries were: first, that they implicitly regarded potential migration source areas such as Frisia, northern Germany and Schleswig-Holstein as regions lacking their own genetic prehistory of intrusion running parallel to England; and second, that they did not adequately consider a deeper timescale of North European migrations to the British Isles.

A Pacific proverb runs thus: ‘To know where we are going, we have to know where we are; to know that we have to know where we came from.’ I would add to that ‘… and when’. Although the phylogeographic method I have used in this book demonstrated substantial migrations from Northern Europe dating to the Neolithic and the Bronze Age, it failed to identify any specific founding male gene clusters to match the Anglo-Saxon invasion, probably reflecting the recent nature of the event and its relatively small size. Exact STR matching did, however, suggest a specific immigration sourced from the putative Anglo-Saxon homeland, but amounting to only 5.5% of ancestors for modern English people.

In the next chapter I go on to use both these methods to trace evidence of Viking invasions, for which the literary and archaeological evidence is much more abundant. In the event, both the methods I used produce results consistent with each other and with the known distribution of Viking settlements.

HE

V

IKINGS

The genetic trail still has more mileage in the few hundred years after the Anglo-Saxon hegemony. For five hundred years the Saxons made their mark, if not as large as previously thought in the genetic heritage of Britain, then certainly in culture and in clerical and historical records, not to forget the shire names. But those records increasingly complain of fresh invaders from across the water. These were raiders from Denmark and Norway.

This time there were more, and better, historians to record ‘awful events’ than the prophet St Gildas. Although the new incursions were much better documented than the Anglo-Saxon invasions, the English chronicles are still biased towards the more gory details. English historians identified these intrusive Danes and Norwegians non-specifically as ‘Vikings’, while the

Carolingians called them ‘Northmen’. The Danish historian Saxo Grammaticus, gives the raiders no special label, just their geographical origin, in his

Gesta Danorum

– which is perhaps not surprising, considering his perspective. Presumably, they were more or less the same old Scandinavians, with the same seafaring skills possessed by their ancestors of the previous few hundred years, just behaving badly overseas.