The Norm Chronicles (33 page)

Read The Norm Chronicles Online

Authors: Michael Blastland

On top of that, another 1 or 2 in every 100 lose a job to become inactive – unemployed but not looking for work. Sometimes people are classed as inactive not because they don’t want a job but because they’ve given up looking.

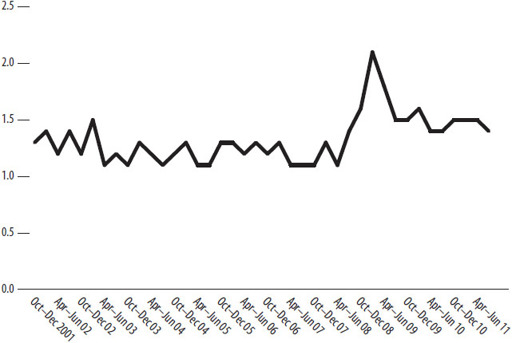

Figure 23:

The hazard of unemployment: the proportion of the employed losing their job every three months

3

Round up these three-monthly percentages into annual totals and turn them into numbers of real people and we find out where those startling numbers come from: nearly 4 million jobs are actually lost each year to unemployment or inactivity. Four years of that gives the approximately 15 million total of lost jobs from the start of the recession in 2008 to 2012.

There’s another surprise in how this risk changes. Before the recession, the average risk of losing a job to become unemployed was about 1.5 per cent. It spiked briefly at about 2 per cent, then fell back. The difference from pre- to post-recession, from steady economic growth to slow or no growth, was equal to only about 0.2 per cent, or 1 extra person in every 500 losing a job every three months.

An additional risk of 0.2 per cent does not sound threatening, but people did feel threatened. Surveys suggested that the fear of redundancy was widespread. In fact, the hazard of unemployment doesn’t change as much as we might expect. The hazard of inactivity didn’t change much either. In fact, it may even have fallen slightly, meaning a slightly lower risk of becoming inactive.

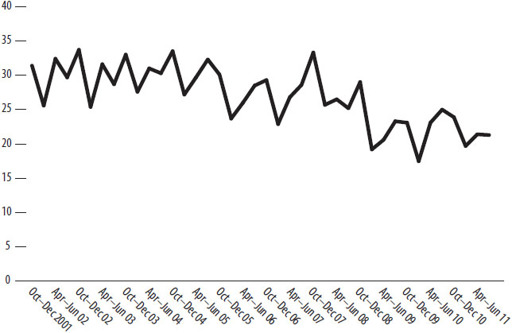

Figure 24:

The hazard of employment: the percentage of unemployed finding a new job within three months

This is a puzzle. Why does unemployment rise so much if the hazard for the average worker doesn’t? The answer to the puzzle is partly that we’re looking in the wrong place. More significant is what happened at the other end of the story, to the chance of finding a new job if you didn’t have one, of getting back through the door once you were out. This is known, curiously, as the ‘hazard of employment’.

In the years before the recession up to a third of the unemployed were back in a job inside three months. After the recession, this peaked significantly lower, at about a quarter or less.

*

The habit of reporting rising unemployment as if it were all about firms losing business or going bust is misleading; a big part of the story is

to do with businesses not opening or expanding. But it is hard to report the nothing of a new job not appearing. It’s much easier to show the shutters coming down. Hence ‘Becker’s Law’: ‘It’s much harder to find a job than to keep one.’

4

One reason it’s harder is that the number of people trying to find work is growing all the time in a rising population. Normally, extra people are soaked up by an increasing number of jobs. This was not often the case between 2008 and 2012. More of the increased workforce stayed on the wrong side of the door.

But it is against the vast, constant labour market churn that the extra threat in hard times of losing your job – affecting about 1 person in every 500, every three months – appears small. To change the metaphor, we are looking at a change in the waves on top of an always heaving ocean.

So the rise in the number of unemployed is the small difference between huge flows of people in both directions, out of work and into work, a difference owed to the difficulty of finding a job as well as the risk of losing one, plus the extra people wanting work every year and lowering the chance for any individual. Amid this great, perpetual flux the

change

in the risk for the average person of losing a job – if they already have one – is small. If you thought it was too high in 2012, you would have to say that it is always too high.

Another way of talking about unemployment is to say that the risk is misery (the probability/consequence distinction rears its head again). According to one study, it is about as bad for our health as smoking. For the young, especially, it leaves a permanent scar on job prospects and wages.

One measure of the consequences is whether unemployment really does become a scrapheap: that is, how long it lasts. In early 2008 about 400,000 had been unemployed for more than 12 months. By early 2012 this was up to about 800,000. So this risk roughly doubled. Your chance of becoming one of them, even if you did lose your job, was still small, but the consequences could be desperate.

That’s something only you can judge. Losing a job might be the chance you were looking for to escape and learn dry-stone walling or cash in the redundancy cheque and blow the kids’ inheritance on

foreign travel, in which case the consequential risk is only that you might enjoy yourself.

Or it might also be catastrophic. In 2010 the TUC, a federation of trade unions in the UK, publicised the story of Christelle Pardo as a warning of the costs of unemployment. With no job, on benefits, pregnant and with a five-month-old baby in her arms, she jumped to her death from the balcony of her sister’s flat in Hackney, London.

Her Jobseeker’s Allowance had been stopped because of her pregnancy and this meant that she also lost her Housing Benefit: the local authority was demanding that she return £200 in overpaid HB. She had been turned down for other benefits – her appeals had been turned down twice; her last call to the DWP [Department of Work and Pensions] was made just the day before her suicide. Ms Pardo died almost immediately, her son later that day.

5

Terrible, but a fair reflection of the risk? Losing a job is unlikely in itself to kill you, but the consequences might. Apart from the loss of income, you are also more likely to divorce, commit crime, suffer ill health and die early. Suicide is often said to be one factor in this rising mortality rate; others are heart disease and alcohol. In short, the unemployed are more likely to be stressed, depressed, broke and sick.

Estimates of the extra risk of an early death vary widely. One study found no effect;

6

others put it at around 20 per cent, with suicide up within a year, cardiovascular mortality rising after about two years and continuing for more than a decade.

7

A third said the overall increase in mortality as a result of unemployment is nearer 60 per cent.

8

That is huge, equal to about an extra 6 MicroLives every day and similar to the extra risk of being an average smoker.

Is the health effect of a day’s unemployment really equivalent to that of a dozen cigarettes, bringing you to death that much sooner, as if every 24-hour day without work left you 27 hours older?

But the problem is not as simple as comparing body counts of the employed and unemployed. Untangling cause and effect in these cases

is tricky. Are the unhealthy and unhappy more likely to be unemployed anyway, in which case they might die early for the same reason that they don’t have a job, but not

because

they don’t have a job? Or is unemployment what makes them unhealthy and unhappy?

One study tried to separate the two by ignoring deaths until a few years after unemployment struck, hoping to weed out anyone who lost a job because they were already unhealthy.

9

It also noted that people who are unemployed because they are sick are usually now on sickness benefit and no longer count as unemployed. Its conclusion was that the extra mortality found among the unemployed was overwhelmingly caused directly by unemployment itself.

The size of this fatal effect is still up for grabs, but on current evidence it is probably real. There is also evidence that young people who experience six months’ or more unemployment see sharply lower wages in the next few years, and even 20 years later are still earning 8 per cent less than those who stayed in work.

10

Studies of young people who were unemployed for more than six months in the 1980 and 1990 recessions found that even five years later they spent more than 20 per cent of their time unemployed, and 15 per cent even twelve years later.

11

High impacts can endure. As Norm has found, risk can take more forms than accidents, and it’s not just sausages and cigarettes that can make their effects felt a long way into the future. Nor is it only fatal incidents that can turn out fatally, nor just the known, expected or calculable dangers that are dangerous. So all in all, black swans are even more troublesome than sometimes supposed. First, we cannot predict them; second, we often don’t recognise them when they arrive. That is, we might not know whether what we just saw was a black swan until well after it has floated past and its full effect is clear. The 2008 banking crisis was still playing out five years later in 2013, and probably will continue to do so for years to come. Similarly, Norm might not know the risks of unemployment, even after he is shown the door, until years later. So what was the risk?

22

CRIME

P

RUDENCE CHECKED HER EMAILS

, deleted two financial ‘opportunities’ from Nigeria, turned off the laptop and popped it under the cupboard in the downstairs loo, took a last look outside and then bolted the front door and put on the chain, switched on the alarm, turned off the lights and went upstairs. She thought again about a dog, especially now that she was alone after her husband had died of prostate cancer, only to run round the same old houses about fleas and mud versus at least a warning bark – and then dismiss the idea. Outside in the wind a tree branch waved into view of the sensor on the security light, switching it on. At the sudden glow in the bathroom window, she twitched, and pulled her dressing-gown tighter. It was two years since they had been burgled. She knew already that she wouldn’t sleep.

K2’s diary

*

No job. Naturally, go clubbing.

Eight pints = low dosh.

Dosh trip with Kate + fresco shag option.

Old bloke at cashpoint with dog.

Dog is snarly dog. Dog snarls. Bloke kicks dog. Snarly dog bites bloke hand

Big cut. Oozes claret.

Also kick dog.

OB says no one kicks dog, kicks yrs truly knee + language.

Kate bends over helps up yrs truly. Cleavage. Nice.

Old bloke gobs at yrs truly but drops dosh.

In consideration of old bloke being knee-kicking/gobbing bastard, and old, shove bloke to ground as he reaches for dosh, grab dosh, tell Kate leg it.

Owing to lack of forethought about efficacy of legging it on bad leg, bloke on floor able to grab bad leg.

With free/good leg kick bloke in head. Language.

Note one foot off ground re kick. Note other foot off ground re grabbed bad leg.

Owing to no feet on ground, fall on bloke.

Dog bites good leg. Bloke bites head.

Pain/claret.

Old bloke fierce bastard. Grinds yrs truly face in ground.

Claret.

Kate multiple smashes OB in head with stiletto.

Claret.

OB stamps on hand, grabs dosh, kicks to various body parts inc. stomach, original bad leg, back. Nicks mobile and wallet inc. cards.

OB legs it + dog. OB nifty for an OB. Conclude later OB probably a crim. Streets not safe.