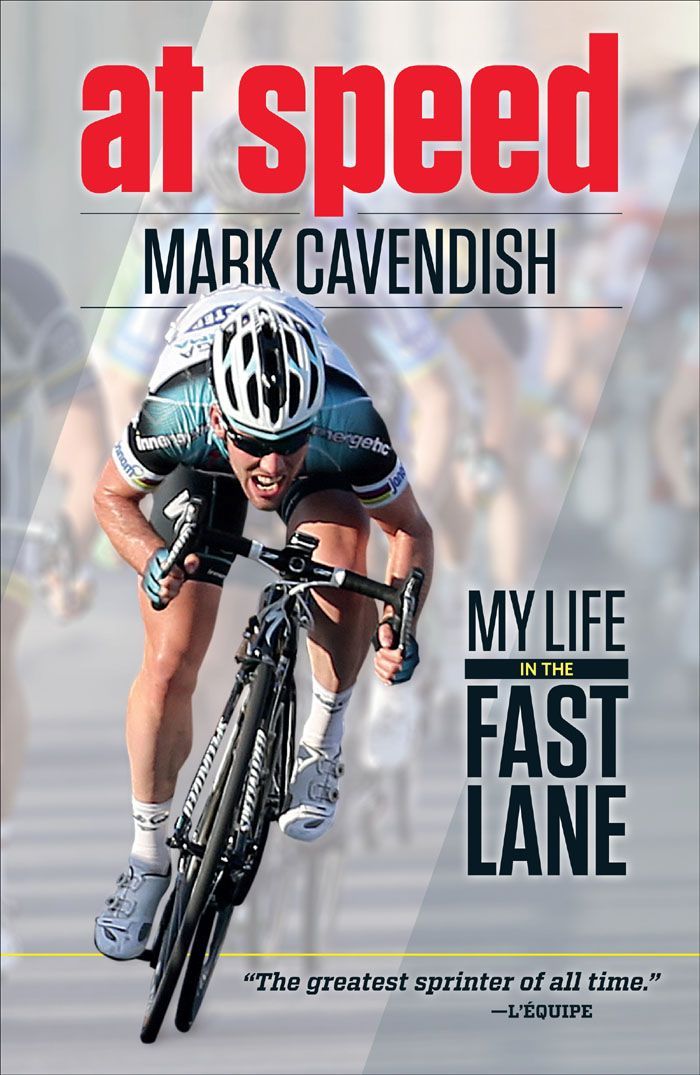

At Speed: My Life in the Fast Lane

Read At Speed: My Life in the Fast Lane Online

Authors: Cavendish Mark

Boy Racer

BY

M

ARK

C

AVENDISH

“

Boy Racer

is an emotional, fast-paced and direct account of Cav’s transformation from awkward chubby teenager to world champion and Tour stage winner.”

— V

ELO

MAGAZINE

“

Boy Racer

is Mark Cavendish’s brash, brutal and honest story of his life on the bike, full of the sound and fury of hand-to-hand combat at the finish line. Cavendish holds nothing back.”

— USA T

ODAY

“Mouthy former fat kid races bikes, kicks ass, hilarity ensues.”

— B

ICYCLING

MAGAZINE

“Like being hard-wired into the brain of the world’s fastest sprinter. [

Boy Racer

is] the closest to finding out what it feels like to be in the midst of a bunch sprint.”

—

C

YCLE

S

PORT

MAGAZINE

“T

HE

B

EST

50 C

YCLING

B

OOKS OF

A

LL

T

IME”

“Few have brought the terrifying and visceral art of sprinting to life.

Boy Racer

redresses the balance.”

—

T

HE

T

IMES

“

Boy Racer …

catch[es] the inner conflict between the impetuousness that makes Cavendish such a daunting competitor and the introspection that makes him such an interesting person.”

— T

HE

G

UARDIAN

Copyright © 2014 by Mark Cavendish

First Published in 2013 by Ebury Press, an imprint of Ebury Publishing, A Random House Group company

All rights reserved. U.S edition published in the United States of America by VeloPress, a division of Competitor Group, Inc.

3002 Sterling Circle, Suite 100

Boulder, Colorado 80301-2338 USA

(303) 440-0601 · Fax (303) 444-6788 · E-mail

[email protected]

Distributed in the United States and Canada by Ingram Publisher Services

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition of this book as follows:

Cavendish, Mark.

At speed : my life in the fast lane / Mark Cavendish.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-937715-04-5 (pbk. : alk. paper); ISBN 978-1-937716-49-3 (e-book)

1. Cavendish, Mark. 2. Cyclists—Great Britain—Biography. I. Title.

GV1051.C39A3 2014

796.6092—dc23

[B]

2013041075

For information on purchasing VeloPress books, please call (800) 811-4210, ext. 2138, or visit

www.velopress.com

.

Cover design, interior design, and composition by Anita Koury

Cover photograph by Karim Jaafar, Getty Images

All interior photographs courtesy of Getty Images (

Fabrice Coffrini

,

Mark Gunter

,

Joel Sagat

,

Pascal Pavani

,

AFP

,

Bryn Lennon

,

Scott Mitchell

,

Scott Mitchell

,

WPA Pool

,

Bryn Lennon

,

John Berry

,

John Berry

), with the exception of the

author’s own photograph

of his family

Version 3.1

For Delilah

| | ||

| | ||

| | ||

| | ||

| | ||

| | ||

| | ||

| | ||

| | ||

| | ||

| |

d

ave, I’m going to win the worlds tomorrow.”

Dave was Dave Millar and I was already the world champion in my own imagination. It was midafternoon on Saturday, September 24, 2011, and we’d just watched Giorgia Bronzini from Italy win the women’s world championships road race on a TV in our hotel room. Before Bronzini, the previous day, a 20-year-old Frenchman named Arnaud Démare had taken the men’s Under 23 race, and before Démare, Lucy Garner of Great Britain had been the first of the junior women to cross the line.

Rod Ellingworth, my coach and the British team’s that week, had stuck his head out of the car window and broken the good news about Lucy while we, the senior men, were on a tough final training ride. When Garner had got back to the hotel where the whole GB squad was staying, I’d been with an old teammate, the Swede Thomas Löfkvist, tinkering with my bike, but stopped to applaud Lucy as she walked in. As I clapped, my eyes had wandered toward the rainbow stripes of her new world champion’s jersey—then I’d quickly averted them out of superstition. That jersey—maybe the most sought-after in professional cycling, more than even the Tour de France’s yellow jersey—was one thing that Bronzini’s race, Démare’s, and Garner’s

all had in common. Another was a course circling a leafy suburb to the north of Copenhagen. And another was the way that the races had all ended: in a sprint. Twice could be coincidence, but three times was a pattern.

I turned in my single bed to face Dave. “Dude, I’m going to fucking win this. We can’t lose.” Dave later told me that this was the moment when he knew as well. No sooner had I said it than I was already diving between gaps on a finishing straight tarmacked across my mind’s eye, already ducking for the line and feeling the elation of victory hit me like an ocean wave. I’d been complacent about winning races before in my career but I’d also, gradually, learned the difference between healthy and unhealthy confidence: one energized and sharpened your instincts, your muscles, even your eyesight in the race; the other dulled, muffled, and slowed everything. This was definitely the first kind.

Almost a year earlier, I’d gone with my old mate and HTC-Highroad directeur sportif, Brian Holm, to take a first look at the course. Brian is just about the best-connected man in Denmark and also the fourth-best-dressed according to

GQ

(though I’m not so sure). We’d done a lot on that trip besides ride our bikes, but the time we spent doing loops of the circuit with donors to Brian’s cancer charity convinced me that this wouldn’t be another Melbourne.

The Australian city had been the venue for the 2010 worlds, which had taken place a few weeks before my visit to Copenhagen. Melbourne had not gone well. I was coming off a successful 2010 Vuelta a España, having won three stages and the points jersey, and I was flying. Therein lay the problem and the excuse I gave myself for pushing too hard in pre-race training sessions that were intended to

put the icing and a cherry on my form. I thought I could win it, but my overzealousness in training jeopardized my chances in the race proper. Dave, one of only three British riders who had qualified for the race, knew I was overdoing it, as did the rest of the team and the staff, but it took that mistake and the resulting, massively disappointing performance to teach me what proved to be an absolutely vital lesson.

All week in the run-up to the Copenhagen race, the atmosphere in the British camp had been fantastic. Everyone was rallied around the same cause—namely, making sure that the peloton was bunched together as we came into the last 200 meters of the 266 kilometers, whereupon it’d be handed over to me. It was a measure of my confidence, not only in the nature of the course but also in the guys, that I could only foresee one outcome.

The evening before the race, Brian came to our team hotel. I was getting my massage when he arrived, so Brian chatted to Dave and Brad Wiggins while he waited.

“I saw the races today. You’re going to win this, aren’t you?” Brian said when I finally appeared.

“Yeah, I am. I’m going to win,” I told him.

Brian paused. “Shit, I’m nervous.”

Nervous

, I think, was the wrong word. I think he meant that he was excited. Brian always says that when I’m sure I’m unbeatable, as I was that day. It’s been the same ever since we first met at the Tour of Britain in 2006, when I was a mouthy, 21-year-old stagiaire—cyclingspeak for an amateur getting a tryout with the big boys—and he called me a “fat fuck” for disobeying his orders to get to the front midway through the very first stage.

Over the years, Brian had become a kind of father, brother, and mentor. I was lucky to be rooming with another one of those that week in Dave. There are some riders, like Brad, who will always room alone given the choice, but it drives me absolutely crazy. If a roommate goes home early from a race or training camp, I’m climbing the walls within hours, pestering the management to be put with someone else.

Dave and I woke to sunshine the morning of the race. We ate breakfast, got ready, and then climbed onto the bus. I was quiet—quieter than usual. I rarely get nervous because I keep my mind too busy. Sudoku, logic puzzles, visualization. All full gas. Every pro bike rider trains his legs but very few train their minds, the only muscle they use to make decisions in races. It mystifies me; the more you keep your brain active, the more it’s whirring away and the less likely it is to get sabotaged by the kind of anxiety that can cause mistakes and compromise a performance.

Winning the worlds, and before that ensuring it finished in a sprint, was also a logic puzzle that needed to be solved. To help us, in the days leading up to the race, we’d spoken to other teams who also had strong sprinters and might therefore want the same kind of finale—the Americans, the Australians, and the Germans. They’d said they’d give us a hand, but we all knew that the main responsibility would fall to the team with the fastest sprinter, unanimously acknowledged—namely me. For that reason, it was better that we were prepared to lead the race for all 266 km, something that for any other team would be an impossible task, but that this one was going to relish. It took a special group of guys to achieve that; there would be no personal glory for my teammates, only sacrifice for the benefit of a rider who, for most of them, was an opponent in every other race of the season.