The New Penguin History of the World (202 page)

Read The New Penguin History of the World Online

Authors: J. M. Roberts,Odd Arne Westad

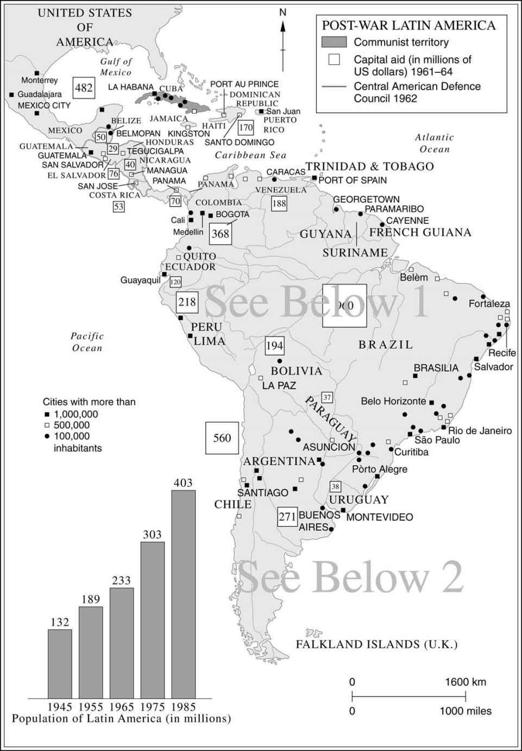

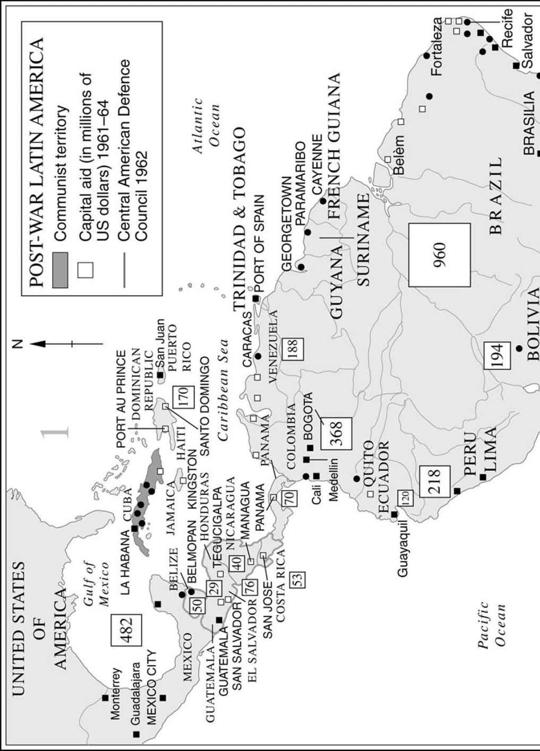

A significant change had also come about (though not as a result of war) in the way the United States used its preponderant power in the Caribbean. Twenty times in the first twenty years of the century American armed forces had intervened directly in neighbouring republics, twice going so far as to establish protectorates. Between 1920 and 1939 there were only two such interventions, in Honduras in 1924 and Nicaragua two years later. By 1936, there were no US forces anywhere in the territory of a Latin American state except by agreement (at the Guantanamo base, in Cuba). Indirect pressure also declined. In large measure this was a sensible recognition of changed circumstances. There was nothing to be got by direct intervention in the 1930s and President Roosevelt made a virtue of this by proclaiming a ‘Good Neighbour’ policy (he used the phrase for the first time, significantly, in his first inaugural address) that stressed non-intervention by all American states in one another’s affairs. (Roosevelt was also the first president of the United States ever to visit a Latin American country on official business.) With some encouragement from Washington, this opened a period of diplomatic and institutional cooperation across the continent (which was encouraged, too, by the worsening international situation and growing awareness of German interests at work there). It succeeded in bringing an end to the bloody ‘Chaco War’ between Bolivia and Paraguay, which raged from 1932 to 1935, and it culminated in a declaration of Latin American neutrality in 1939 which proclaimed a 300-mile neutrality zone in its waters. When, in the following year, a United States cruiser was sent to Montevideo to stiffen the resistance of the Uruguayan government to a feared Nazi coup, it was more evident than ever that the Monroe doctrine and its ‘Roosevelt corollary’ had evolved almost silently into something more like a mutual security system.

After 1945, Latin America was again to reflect a changing international situation. While United States policy was dominated by European concerns in the early phase of the Cold War, after Korea it began slowly to look southwards again. Washington was not unduly alarmed by occasional manifestations of Latin American nationalism, for all its anti-

Yanqui

flavour, but became increasingly concerned lest the hemisphere provide a lodgement for Russian influence. With the Cold War came greater selectivity in United States support to Latin American governments. It also led, at times, to covert operations: for example, to the overthrow in 1954 of a government in Guatemala that had communist support.

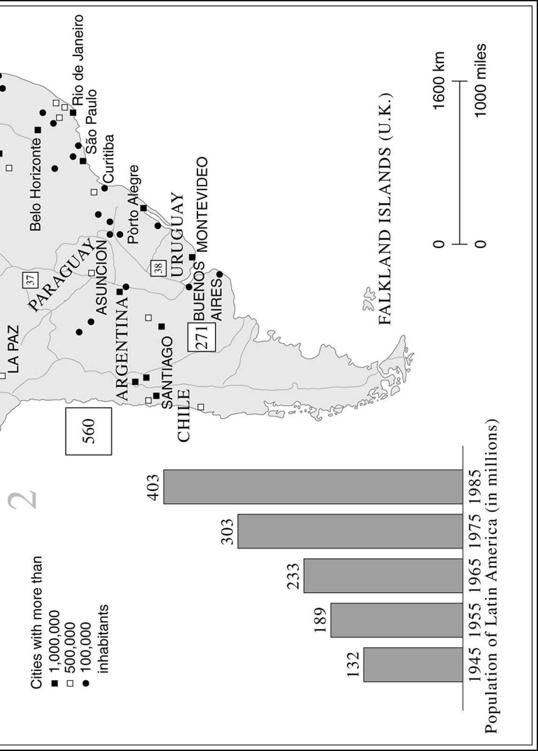

At the same time United States policy-makers were anxious that the footholds provided for communism by poverty and discontent should be removed. They provided more economic aid (Latin America had only a tiny fraction of what went to Europe and Asia in the 1950s, but much more in the next decade) and applauded governments that said they sought social reform. Unfortunately, whenever the programmes of such governments moved towards the eradication of American control of capital by nationalization, Washington tended to veer away again, demanding compensation on such a scale as to make reform very difficult. On the whole,

therefore, while it might deplore the excesses of an individual authoritarian regime, such as that of Cuba before 1958, the American government tended to find itself, as in Asia, supporting conservative interests in Latin America. This was not invariably so; some governments acted effectively, notably Bolivia, which carried out land reform in 1952. But it remained true that, as for most of the previous century, the worst-off Latin Americans had virtually no hearing from either populist or conservative rulers, in that both listened only to the towns – the worst-off, of course, were the peasants, for the most part American Indians by origin.

Yet, for all the nervousness in Washington, there was little revolutionary activity in Latin America. This was in spite of the victorious revolution in Cuba, of which much was hoped and feared at the time. It was in a number of respects a very exceptional problem. Cuba’s location within a relatively short distance of the United States gave it special significance. The approaches to the Canal Zone had often been shown to have even more importance in American strategic thinking than Suez in the British. Secondly, Cuba had been especially badly hit in the Depression; it was virtually dependent on one crop, sugar, and that crop had only one outlet, the United States. This economic tie, moreover, was only one of several that gave Cuba a closer and more irksome ‘special relationship’ with the United States than had any other Latin American state. There were historic connections that went back before 1898 and the winning of independence from Spain. Until 1934 the Cuban constitution had included special provisions restricting Cuba’s diplomatic freedom. The Americans still kept their naval base on the island. There was heavy American investment in urban property and utilities, and Cuba’s poverty and low prices made it attractive to Americans looking for gambling and girls. All in all, it should not have been surprising that Cuba produced, as it did, a strongly anti-American movement with much popular support.

The United States was long blamed as the real power behind the conservative post-war Cuban regime, although after the dictator Batista came to power in 1952 this in fact ceased to be so; the State Department disapproved of him and cut off help to him in 1957. By then, a young nationalist lawyer, Fidel Castro, had already begun a guerrilla campaign against his government. In two years he was successful. In 1959, as prime minister of a new, revolutionary, Cuba, he described his regime as ‘humanistic’ and, specifically, not communist.

Castro’s original aims are still not known. Perhaps he was not clear himself what he thought. From the start he worked with a wide spectrum of people who wanted to overthrow Batista, from liberals to Marxists. This helped to reassure the United States, which briefly patronized him as

a Caribbean Sukarno; American public opinion idolized him as a romantic figure and beards became fashionable among American radicals. The relationship quickly soured once Castro turned to interference with American business interests, starting with agrarian reform and the nationalization of sugar concerns. He also denounced publicly those Americanized elements in Cuban society that had supported the old regime. Anti-Americanism was a logical means – perhaps the only one – open to Castro for uniting Cubans behind the revolution. Soon the United States broke off diplomatic relations with Cuba and began to impose other kinds of pressure as well. The American government became convinced that the island was likely to fall into the hands of the communists upon whom Castro increasingly relied. It did not help when the Soviet leader Khrushchev warned the United States of the danger of retaliation from Soviet rockets if it acted militarily against Cuba and declared the Monroe doctrine dead; the State Department quickly announced that reports of its demise were greatly exaggerated. Finally, the American government decided to promote Dr Castro’s overthrow by force.

It was agreed that this should be done by Cuban exiles. When the presidency changed hands in 1961, John Kennedy inherited this decision. Exiles were already training with American support in Guatemala, and diplomatic relations with Cuba had been broken off. Kennedy had not initiated these activities, but he was neither cautious nor thoughtful enough to impede them. This was the more regrettable because there was much else that boded well in the new president’s attitude to Latin America, where it had been obvious for some time that the United States needed to cultivate goodwill. As it was, the possibilities of a more positive approach were almost at once blown to pieces by the fiasco known as the ‘Bay of Pigs’ operation, when an expedition of Cuban exiles, supported by American money and arms, came to a miserable end in April 1961. Castro now turned in earnest towards Russia, and at the end of the year declared himself a Marxist-Leninist.

A new and much more explicit phase of the Cold War then began in the western hemisphere, and began badly for the United States. The American initiative incurred disapproval everywhere because it was an attack on a popular, solidly based regime. Henceforth, Cuba was a magnet for Latin American revolutionaries. Castro’s torturers replaced Batista’s and his government pressed forward with policies that, together with American pressure, badly damaged the economy, but embodied egalitarianism and social reform (in the 1970s, Cuba claimed to have the lowest child mortality rates in Latin America).

Almost incidentally and as a by-product of the Cuban revolution there

soon took place the most serious superpower confrontation of the whole Cold War and perhaps its turning point. It is not yet known exactly why or when the Soviet government decided to install in Cuba missiles capable of reaching anywhere in the United States, and thus roughly to double the number of American bases or cities that were potential targets. Nor is it known whether the initiative came from Havana or Moscow. Although Castro had asked the USSR for arms, it seems likeliest that it was the second. But whatever the circumstances, American photographic reconnaissance confirmed in October 1962 that the Russians were building missile sites in Cuba. President Kennedy waited until this could be shown to be incontrovertible and then announced that the United States Navy would stop any ship delivering further missiles to Cuba and that those already in Cuba would have to be withdrawn. One Lebanese ship was boarded and searched in the days that followed; Soviet ships were only observed. The American nuclear striking force was prepared for war. After a few days and some exchanges of personal letters between Kennedy and Khrushchev, the latter agreed that the missiles should be removed.

This crisis by far transcended the history of the hemisphere, and its repercussions outside it are best discussed elsewhere. So far as Latin American history is concerned, even though the United States promised not to invade Cuba, it went on trying to isolate it as much as possible from its neighbours. Unsurprisingly, the appeal of Cuba’s revolution nevertheless seemed for a while to gain ground among the young of other Latin American countries. This did not make their governments more sympathetic towards Castro, especially when he began to talk of Cuba as a revolutionary centre for the rest of the continent. In the event, as an unsuccessful attempt in Bolivia showed, revolution was not likely to prove easy. Cuban circumstances had been very atypical. The hopes entertained of mounting peasant rebellion elsewhere proved illusory. Local communists in other countries deplored Castro’s efforts. Potential recruits and materials for revolution turned out to be on the whole urban rather than rural, and middle-class rather than peasants; it was in the major cities that guerrilla movements were within a few years making the headlines. Despite being spectacular and dangerous, it is not clear that they enjoyed wide popular support, even if the brutalities practised in dealing with them alienated support from authoritarian governments in some countries. Anti-Americanism meanwhile continued to run high. Kennedy’s hopes for a new American initiative, based on social reform – an ‘Alliance for Progress’ as he termed it – made no headway against the animosity aroused by American treatment of Cuba. His successor as president, Lyndon Johnson, did no better, perhaps because he was less interested in Latin America than

in domestic reform. The initiative was never recaptured after the initial flagging of the Alliance. Worse still, it was overtaken in 1965 by a fresh example of the old Adam of intervention, this time in the Dominican Republic, where, four years before, American help had assisted the overthrow and assassination of a corrupt and tyrannical dictator and his replacement by a reforming democratic government. When this was pushed aside by soldiers acting in defence of the privileged, who felt threatened by reform, the Americans cut off aid; it looked as if, after all, the Alliance for Progress might be used discriminately. But aid was soon restored – as it was to other right-wing regimes. A rebellion against the soldiers in 1965 resulted in the arrival of 20,000 American troops to put it down.