The New Penguin History of the World (197 page)

Read The New Penguin History of the World Online

Authors: J. M. Roberts,Odd Arne Westad

Yet the Red Guards’ enthusiasm had been real, and the ostentatious moral preoccupations that surfaced in this still in some ways mysterious episode remain striking. Mao’s motives in launching it were no doubt mixed. Besides seeking vengeance on those who had brought about the abandonment of the Great Leap Forward, he appears really to have felt a danger that the Revolution might congeal and lose the moral

élan

that had carried it so far. In seeking to protect it, old ideas had to go. Society, government and economy were enmeshed and integrated with one another in China as nowhere else. The traditional prestige of intellectuals and scholars still embodied the old order, just as the examination system had done as the century began. The ‘demotion’ and demonization of intellectuals was urged as a necessary consequence of making a new China. Similarly, attacks on family authority were not merely attempts by a suspicious regime to encourage informers and disloyalty, but attempts to modernize the most conservative of all Chinese institutions. The emancipation of women and propaganda to discourage early marriage had dimensions going beyond ‘progressive’ feminist ideas or population control; they were an assault on the past such as no other revolution had ever made, for in China the past meant a role for women far inferior to anything to be found in pre-revolutionary America, France or even Russia. The attacks on party leaders, which accused them of flirtation with Confucian ideas, were much more than jibes; they could not have been paralleled in the West, where for centuries there was no past so solidly entrenched to reject. In that light, the Cultural Revolution, too, could be regarded as an exercise in modernization politics.

Yet rejection of the past is only half the story. More than two thousand years of a continuity stretching back to the Ch’in and perhaps further also shaped the Chinese Revolution. One clue is the role of authority in it. For all its cost and cruelty, that revolution was a heroic endeavour, matched in scale only by such gigantic upheavals as the spread of Islam, or Europe’s assault on the world in early modern times. Yet it was different from those upheavals because it was at least in intention centrally controlled and directed. It is a paradox of the Chinese Revolution that it has rested on popular fervour, but is unimaginable without conscious direction from a state inheriting all the mysterious prestige of the traditional bearers of the Mandate of Heaven. Chinese tradition respects authority and gives it a moral endorsement that has long been hard to find in the West. No more than any other great state could China shake off its history, and as a result communist government sometimes had a paradoxically conservative appearance. No great nation had for so long driven home to its peoples the lessons that the individual matters less than the collective whole, that authority could rightfully command the services of millions at any cost to themselves in order to carry out great works for the good of the state, that authority is unquestionable so long as it is exercised for the common good. The notion of opposition is distasteful to the Chinese because it suggests social disruption; that implies the rejection of the kind of revolution involved in the adoption of western individualism, though not of Chinese individualism or collective radicalism.

The regime over which Mao presided benefited from the Chinese past as well as destroying it, because his role was easily comprehensible within its idea of authority. He was presented as a ruler-sage, as much a teacher as a politician in a country that has always respected teachers; western commentators were amused by the status given to his thoughts by the omnipresence of the Little Red Book (but forgot the Bibliolatry of many European Protestants). Mao was spokesman of a moral doctrine which was presented as the core of society, just as Confucianism had been. There was also something traditional in Mao’s artistic interests; he was admired by the people as a poet and his poems won the respect of qualified judges. In China, power has always been sanctioned by the notion that the ruler did good things for his people and sustained accepted values. Mao’s actions could be read in such a way.

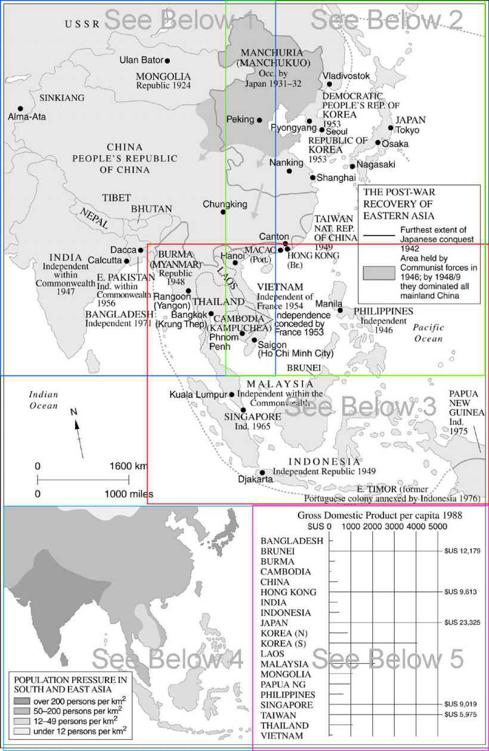

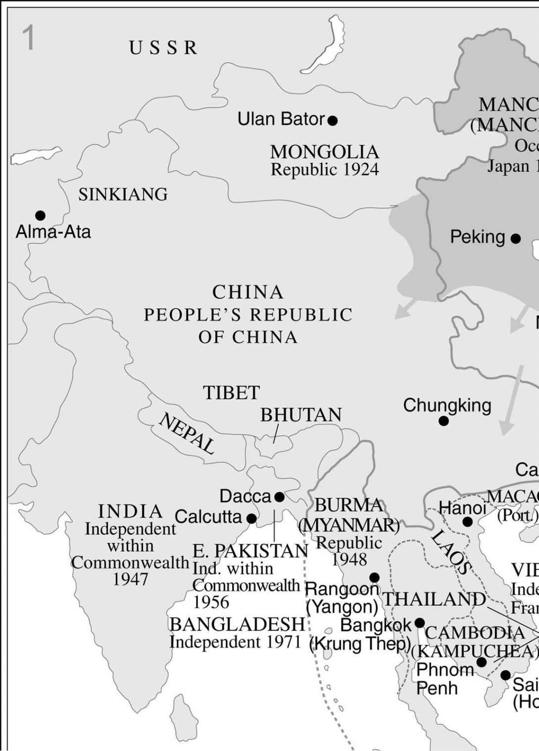

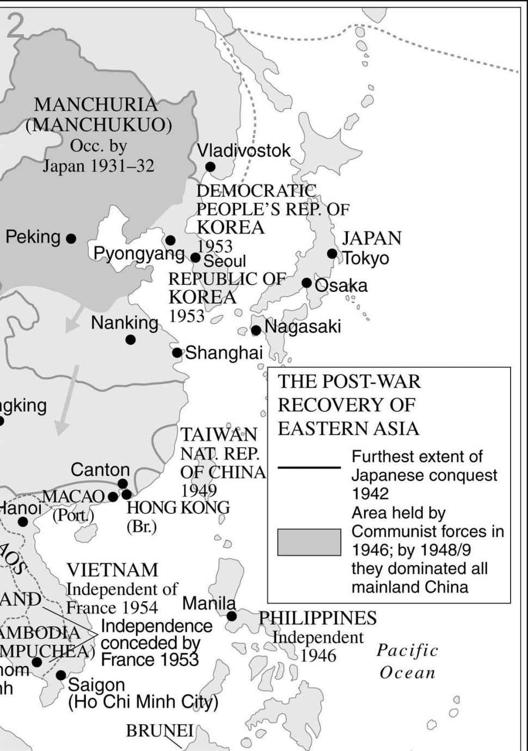

THE CHINESE PERIPHERY AND BEYOND

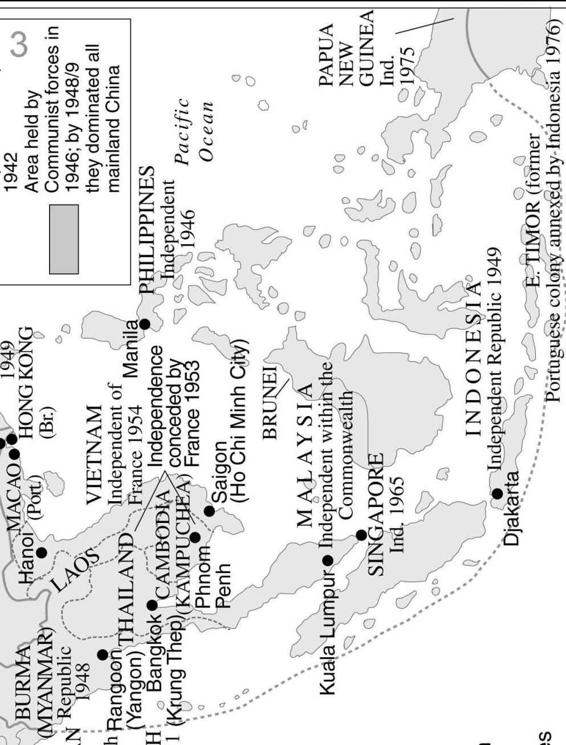

The weight of the past was evident in Chinese foreign policies, too. Although it came to patronize revolution all over the world, China’s main concern was with the Far East and, in particular, with Korea and Indo-China, once tributary countries. In the latter, too, Russian and Chinese policy had diverged. After the Korean War the Chinese began to supply arms to the communist guerrilla forces in Vietnam for what was less a struggle against colonialism – that had been decided already – than about what should follow it. In 1953 the French had given up both Cambodia and Laos. In 1954 they lost at a base called Dien Bien Phu a battle decisive

both for French prestige and for the French electorate’s will to fight. After this, it was impossible for the French to maintain themselves in the Red River delta. A conference at Geneva was attended by representatives from China, which thus formally re-entered the arena of international diplomacy. It was agreed to partition Vietnam between a South Vietnamese government and the communists who had come to dominate the north, pending elections that might reunite the country. The elections never took place. Instead, there soon opened in Indo-China what was to become the fiercest phase since 1945 of an Asian war against the West begun in 1941.

The western contenders were no longer the former colonial powers, but the Americans; the French had gone home and the British had problems enough elsewhere. On the other side was a mixture of Indo-Chinese communists, nationalists and reformers, supported by the Chinese and Russians, who competed for influence in Indo-China. American anti-colonialism and the belief that the United States should support indigenous governments led it to back the South Vietnamese as it backed South Koreans and Filipinos. Unfortunately, neither in Laos nor in South Vietnam, nor, in the end, in Cambodia, did there emerge regimes of unquestioned legitimacy in the eyes of those they ruled. American patronage merely identified governments with the western enemy so disliked in East Asia. American support also tended to remove the incentive to carry out reforms that would have united people behind these regimes, above all in Vietnam, where

de facto

partition did not produce good or stable government in the south. While Buddhists and Roman Catholics quarrelled bitterly and the peasants were more and more alienated from the regime by the failure of land reform, an apparently corrupt ruling class seemed able to survive government after government. This benefited the communists. They sought reunification on their own terms and maintained from the north support for the communist underground movement in the south, the Vietcong.

By 1960 the Vietcong had won control of much of the south. This was the background to a momentous decision taken by the American president, John Kennedy, in 1962; to send not only financial and material help but also 4000 American ‘advisers’ to help the South Vietnam government put its military house in order. It was the first step towards what Truman had been determined to avoid, the involvement of the United States in a major war on the mainland of Asia, and in the end led to the loss of more than 50,000 American lives.

Another of Washington’s responses to Cold War in Asia had been to safeguard as long as possible the special position arising from the American occupation of Japan. This was virtually a monopoly, although there was token participation by British Commonwealth forces. It had been possible

because of the Soviet delay in declaring war on Japan, for the speed of Japan’s surrender had taken Stalin by surprise. The Americans firmly rejected later Soviet requests for a share in an occupation Soviet power had done nothing to bring about. The outcome was the last great example of western paternalism in Asia and a new demonstration of the Japanese people’s astonishing gift for learning from others only what they wished to learn, while safeguarding their own society against unsettling change.

The events of 1945 forced Japan spiritually into a twentieth century it had already entered technologically. Defeat confronted its people with deep and troubling problems of national identity and purpose. The westernization of the Meiji era had seeded a dream of ‘Asia for the Asians’; this was presented as a kind of Japanese Monroe doctrine, underpinned by the anti-western sentiment so widespread in the Far East and cloaking the reality of Japanese imperialism. It had been blown away by defeat, and after 1945 the rolling back of colonialism left Japan with no obvious and credible Asian role. True, at that moment it seemed unlikely for a long time to have the power for one. Moreover, the war’s demonstration of Japan’s vulnerability had been a great shock; like the United Kingdom, its security had rested at bottom upon control of the surface of the sea, and the loss of it had doomed the country. Then there were the other results of defeat; the loss of territory to Russia on Sakhalin and the Kurile islands and the occupation by the Americans. Finally, there was vast material and human destruction to repair.