The New Penguin History of the World (198 page)

Read The New Penguin History of the World Online

Authors: J. M. Roberts,Odd Arne Westad

On the asset side, the Japanese in 1945 still had the unshaken central institution of the monarchy, whose prestige was undimmed and, indeed, had made the surrender possible. Japanese saw in the Emperor Hirohito not the ruler who had authorized the war, but the man whose decision had saved them from annihilation. The American commander in the Pacific, General MacArthur, wanted to uphold the monarchy as an instrument of a peaceful occupation and was careful not to compromise the emperor by parading his role in policy-making before 1941. He took care to have a new Japanese constitution (with an electorate doubled in size and now including women) adopted before republican enthusiasts in the United States could interfere; he found it effective to argue that Japan should be helped economically in order to get it more quickly off the back of the American tax-payer. Japanese social cohesiveness and discipline were a great help, even though for a time it seemed that the Americans might undermine this by the determination with which they pressed democratic institutions upon the country. Some problems must have been eased by a major land reform in which about a third of Japanese farming land passed from landlords’ to cultivators’ ownership. By 1951 democratic education

and careful demilitarization were deemed to have done enough to make possible a peace treaty between Japan and most of its former opponents, except the Russians and nationalist Chinese (with whom terms were to be settled within a few years). Japan regained its full sovereignty, including a right to arms for defensive purposes, but gave up virtually all its former overseas possessions. Thus the Japanese emerged from the post-war era to resume control of their own affairs. An agreement with the United States provided for the maintenance of American forces on its soil. Confined to its own islands, and facing a China stronger and much better consolidated than for a century, Japan’s position was not necessarily a disadvantageous one. In less than twenty years this much-reduced status was, as it turned out, to be transformed again.

The Cold War had changed the implications of the American occupation even before 1951. Japan was separated from the Russians and Chinese by, respectively, 10 and 500 miles of water. Korea, the old zone of imperial rivalry, was only 150 miles away. The spread of the Cold War to Asia guaranteed Japan even better treatment from the Americans, now anxious to see it working convincingly as an example of democracy and capitalism, and also gave it the protection of the United States’ nuclear ‘umbrella’. The Korean War made Japan important as a base and galvanized its economy. The index of industrial production quickly went back up to the level of the 1930s. The United States promoted Japanese interests abroad through diplomacy. Finally, Japan at first had no defence costs, since it was until 1951 forbidden to have any armed forces.

Japan’s close connection with the United States, its proximity to the communist world, and its advanced and stable economy and society, all made it natural that it should eventually take its place in the security system built up by the United States in Asia and the Pacific. Its foundations were treaties with Australia, New Zealand and the Philippines (which had become independent in 1946). Others followed with Pakistan and Thailand; these were the Americans’ only Asian allies other than Taiwan. Indonesia and (much more important) India remained aloof. These alliances reflected, in part, the new conditions of Pacific and Asian international relations after British withdrawal from India. For a little longer there would still be British forces east of Suez, but Australia and New Zealand had discovered during the Second World War that the United Kingdom could not defend them and that the United States could. The fall of Singapore in 1942 had been decisive. Although British forces had sustained the Malaysians against the Indonesians in the 1950s and 1960s, the colony of Hong Kong survived, it was clear, only because it suited the Chinese that it should. On the other hand, there was no question of sorting out the

complexities of the new Pacific by simply lining up states in the teams of the Cold War. The peace treaty with Japan itself caused great difficulty because United States policy saw Japan as a potential anti-communist force while others – notably in Australia and New Zealand – remembered 1941 and feared a revival of Japanese power.

Thus American policy was not created only by ideology. Nonetheless, it was long misled by what was believed to be the disaster of the communist success in China and by Chinese patronage of revolutionaries as far away as Africa and South America. There had certainly been a transformation in China’s international position and it would go further. Yet the crucial fact was China’s re-emergence as a power in its own right. In the end this did not reinforce the dualist, Cold War system, but made nonsense of it. Although at first only within the former Chinese sphere, it was bound to bring about a big change in relative power relationships; the first sign of this was seen in Korea, where the United Nations armies were stopped and it was felt necessary to consider bombing China. But the rise of China was also of crucial importance to the Soviet Union. After being one element of a bipolarized system, Moscow now became the corner of a potential triangle, as well as losing its unchallenged pre-eminence in the world revolutionary movement. And it was in relation to the Soviet Union, perhaps, that the wider significance of the Chinese Revolution most readily appeared. Overwhelmingly important though it was, the Chinese Revolution was only the outstanding instance of a rejection of western domination that was Asia-wide. Paradoxically, of course, that rejection in all Asian countries was constantly expressed in forms, language and mythology borrowed from the West itself, whether they were those of industrial capitalism, democracy, nationalism or Marxism.

THE MIDDLE EAST

The survival of Israel, the coming of the Cold War and a huge rise in the demand for oil revolutionized the politics of the Middle East after 1948. Israel focused Arab feeling more sharply than Great Britain had ever done. It made pan-Arabism look plausible. On the injustice of the seizure of what were regarded as Arab lands, the plight of the Palestine refugees and the obligations of the great powers and the United Nations to act on their behalf, the Arab masses could brood bitterly and Arab rulers were able to agree as on nothing else.

Nonetheless, after the defeat of 1948–9, the Arab states were not for some time disposed again to commit their own forces openly. A formal

state of war persisted, but a series of armistices established for Israel

de facto

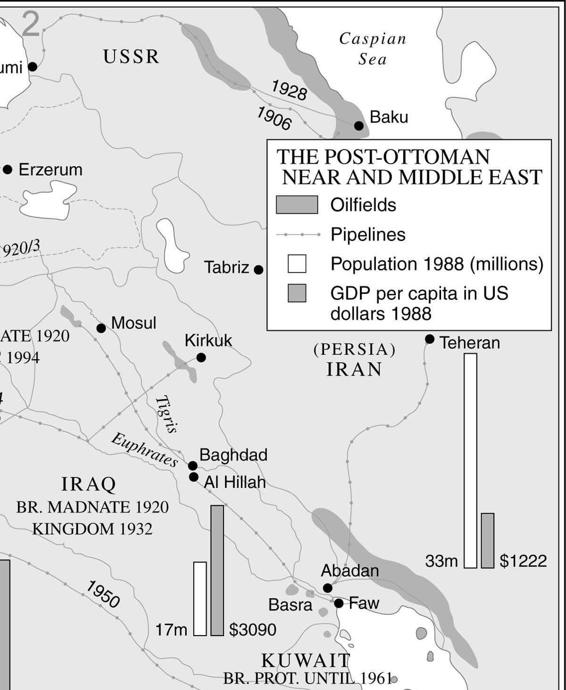

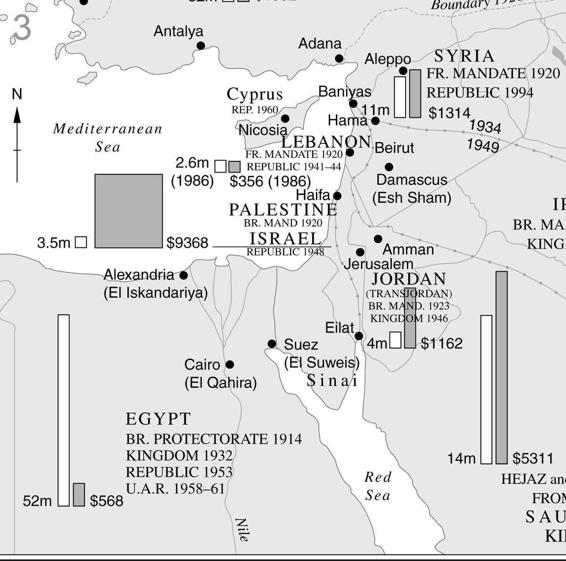

borders with Jordan, Syria and Egypt that lasted until 1967. There were continuing border incidents in the early 1950s, and raids were carried out upon Israel from Egyptian and Syrian territory by bands of young guerrilla soldiers recruited from the refugee camps, but immigration, hard work and money from the United States steadily consolidated the new Israel. A siege psychology helped to stabilize Israel’s politics; the prestige of the party that had brought about the very existence of the new state was scarcely troubled while the Jews transformed their new country. Within a few years they could show massive progress in bringing barren land under cultivation and establishing new industries. The gap between Israel’s per capita income and that of the more populous among the Arab states steadily widened.

Here was another irritant for the Arabs. Foreign aid to their countries produced nothing like such dramatic change. Egypt, the most populous of them, faced particularly grave problems of population growth. While the oil-producing states were to benefit in the 1950s and 1960s from growing revenue and a higher GDP, this often led to further strains and divisions within them. Contrasts deepened both between different Arab states and within them between classes. Most of the oil-producing countries were ruled by small, wealthy, sometimes traditional and conservative, occasionally nationalist and westernized, élites, usually uninterested in the poverty-stricken peasants and slum-dwellers of more populous neighbours. The contrast was exploited by a new Arab political movement, founded during the war, the Ba’ath party. It attempted to synthesize Marxism and pan-Arabism, but the Syrian and Iraqi wings of the movement (it was always strongest in those two countries) had fallen out with one another almost from the start.

Pan-Arabism had too much to overcome, for all the impulse to united action stemming from anti-Israeli and anti-western feeling. The Hashemite kingdoms, the Arabian sheikhdoms, and the Europeanized and urbanized states of North Africa and the Levant all had widely divergent interests and very different historical traditions. Some of them, like Iraq or Jordan, were artificial creations whose shape had been dictated by the needs and wishes of European powers after 1918; some were social and political fossils. Even Arabic was in many places a common language only within the mosque (and not all Arabic-speakers were Muslims). Although Islam was a tie between many Arabs, for a long time it seemed of small account; in 1950 few Muslims talked of it as a militant, aggressive faith. It was only Israel that provided a common enemy and thus a common cause.

Hopes were first awoken among Arabs in many countries by a revolution in Egypt, from which there eventually emerged a young soldier, Gamal Abdel Nasser. For a time he seemed likely both to unite the Arab world against Israel and to open the way to social change. In 1954 he became the leader of the military junta that had overthrown the Egyptian monarchy two years previously. Egyptian nationalist feeling had for decades found its main focus and scapegoat in the British, still garrisoning the Canal Zone, and now blamed for their part in the establishment of Israel. The British government, for its part, did its best to cooperate with Arab rulers because of its fears of Soviet influence in an area still thought crucial to British communications and oil supplies. The Middle East (ironically given the motives that had taken the British there in the first place) had not lost its strategic fascination for the British after withdrawal from India.