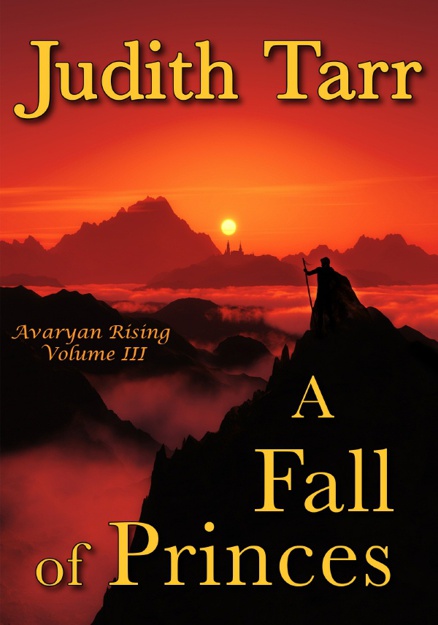

A Fall of Princes

Authors: Judith Tarr

Tags: #Judith Tarr, #Fantasy, #Avaryan, #Epic Fantasy

A FALL OF PRINCES

Avaryan Rising, Volume III

Judith Tarr

Book View Café Edition

July 30, 2013

ISBN: 978-1-61138-269-3

Copyright © 1988 Judith Tarr

To

The Yale Department of Medieval Studies

The Orange Street Gang in all its permutations

And, of course, all the Faithful

But for whom, et cetera.

Asuchirel inZiad Uverias

The hounds had veered away westward. Their baying swelled

and faded as the wind shifted; the huntsman’s horn sounded, faint and deadly.

Hirel flattened himself in his nest of spicefern. His nose

was full of the sharp potent scent. His body was on fire. His head was light

with running and with terror and with the last of the cursed drug with which

they had caught him.

Caught him but not held him. And they were gone. Bless that

wildbuck for bolting across his path. Bless his brothers’ folly for hunting him

with half-trained pups.

He crawled from the fernbrake, dragging a body that had

turned rebel. Damned body. It was all over blood. Thorns. Fangs—one hound had

caught him, the one set on guard by his prison.

It was dead. He hurt. Some fool of a child was crying,

softly and very near, but this was wild country, border country, and he was

alone. It was growing dark.

o0o

The dark lowered and spread wide, shifted and changed,

took away pain and brought it back edged with sickness.

The sky was full of stars. Branches rimmed it; he had not

seen them before. The air carried a tang of fire.

Hirel blinked, frowned. And burst upward in a flood of memory,

a torrent of panic terror.

Those were not cords that bound him, but bandages wrapped

firmly where he hurt most. But for them he was naked; even the rag of his

underrobe was gone, all else left behind in the elegant cell in which he had

learned what betrayal was.

He dropped in an agony of modesty, coiling around his

center, shaking forward the royal mane—but that was gone, his head scraped bare

as a slave’s, worst of all shames even under sheltering arms.

The fire snapped a branch in two. The shadow by it was

silent. Hirel’s pride battered him until he raised his eyes.

The shadow was a man. Barbarian, Hirel judged him at once

and utterly. Even sitting on his heels he was tall, trousered like a southerner

but bare above like a wild tribesman from the north, and that black- velvet

skin was of the north, and that haughty eagle’s face, and the beard left free

to grow. But he held to a strange fashion: beard and long braided hair were

dyed as bright as the copper all his kind were so fond of. Or—

Or he was born to it. His brows were the same, and his

lashes; the fire caught glints of it on arms and breast and belly as he rose.

He was very tall. For all that Hirel’s will could do, his

body cowered, making itself as small as it might.

The barbarian lifted something from the ground and

approached. His braid had fallen over his shoulder. It ended below his waist.

His throat was circled with gold, a torque as thick as two men’s fingers, and a

white band bound his brows.

Priest. Priest of the demon called Avaryan and worshipped as

the Sun; initiate of the superstition that had overwhelmed the east of the

world. He knelt by Hirel, his face like something carved in stone, and he

dared. He touched Hirel.

Hirel flung himself against those blasphemous hands,

screaming he cared not what, striking, kicking, clawing with nails which his

betrayers had not troubled to rob him of. All his fear and all his grief and

all his outrage gathered and battled and hated this stranger who was not even

of the empire. Who had found him and tended him and presumed to lay unhallowed

hands on him.

Who held him easily and let him flail, only evading the

strokes of his nails.

He stopped all at once. His breath ached in his throat; he

felt cold and empty. The priest was cool, unruffled, breathing without strain.

“Let me go,” Hirel said.

The priest obeyed. He stooped, took up what he had held

before Hirel sprang on him. It was a coat, clean but not fresh, tainted with

the touch of a lowborn body. But it was a covering.

Hirel let the barbarian clothe him in it. The man moved

lightly, careful not to brush flesh with flesh. A quick learner, that one. But

his grip was still a bitter memory.

Hirel sat by the fire. He was coming to himself. “A hood,”

he said. “Fetch one.”

A bright brow went up. It was hard to tell in firelight, but

perhaps the priest’s lips quirked. “Will a cap satisfy your highness?” The

accent was appalling but the words comprehensible, the voice as dark as the

face, rich and warm.

“A cap will do,” Hirel answered him, choosing to be gracious.

Covered at last, Hirel could sit straight and eat what the

priest gave him. Coarse food and common, bread and cheese and fruit, with

nothing to wash it down but water from a flask, but Hirel’s hunger was far

beyond criticism. They had fed him in prison, but then they had purged him; he

ached with emptiness.

The priest watched him. He was used to that, but the past

days had left scars that throbbed under those calm dark eyes. Bold eyes in

truth, not lowering before his own, touched with something very like amusement.

They refused to be stared down. Hirel’s own slid aside

first, and he told himself that he was weary of this foolishness. “What are you

called?” he demanded.

“Sarevan.” Why was the barbarian so damnably amused? “And

you?”

Hirel’s head came up in the overlarge cap; he drew himself

erect in despite of his griping belly. “Asuchirel inZiad Uverias, High Prince

of Asanion and heir to the Golden Throne.” He said it with perfect hauteur, and

yet he was painfully aware, all at once, of his smallness beside this long

lanky outlander, and the lightness of his unbroken voice, and the immensity of

the world around their little clearing with its flicker of fire.

The priest shifted minutely, drawing Hirel’s eyes. Both of

his brows were up now, but not with surprise, and certainly not with awe. “So

then, Asuchirel inZiad Uverias, High Prince of Asanion, what brings you to this

backward province?”

“

You

should not be

here,” Hirel shot back. “Your kind are not welcome in the empire.”

“Not,” said Sarevan, “in this empire. You are somewhat

across the border. Did you not know?”

Hirel began to tremble. No wonder the hounds had turned

away. And he—he had told this man his name, in this man’s own country, where

the son of the Emperor of Asanion was a hostage beyond price.

“Kill me now,” he said. “Kill me quickly. My brothers will

reward you, if you have the courage to approach them. Kill me and have done.”

“I think not,” the barbarian said.

Hirel bolted.

A long arm shot out. Once more a lowborn hand closed about

him. It was very strong.

Hirel sank his teeth into it. A swift blow jarred him loose

and all but stunned him.

“You,” said Sarevan, “are a lion’s cub indeed. Sit down,

cubling, and calm your fears. I’m not minded to kill you, and I don’t fancy

holding you for ransom.”

Hirel spat at him.

Sarevan laughed, light and free and beautifully deep. But he

did not let Hirel go.

“You defile me,” gritted Hirel. “Your hands are a

profanation.”

“Truly?” Sarevan considered the one that imprisoned Hirel’s

wrist. “I know it’s not obvious, but I’m quite clean.”

“I am the high prince!”

“So you are.” No, there was no awe in that cursed face. “And

it seems that your brothers would contest your title. Fine fierce children they

must be.”

“They,” said Hirel icily, “are the bastards of my father’s

youth. I am his legitimate son. I was lured into the marches on a pretext of

good hunting and fine singing and perhaps a new concubine.”

The black eyes widened slightly; Hirel disdained to take

notice. “And I was to speak with a weapons master in Pri’nai and a philosopher

in Karghaz, and show the easterners my face. But my brothers—”

He faltered. This was pain. It must not be. It should be

anger. “My dearest and most loyal brothers had found themselves a better game.

They drugged my wine at the welcoming feast in Pri’nai, corrupted my taster and

so captured me. I escaped. I took a senel, but it fell in the rough country and

broke its neck. I ran. I did not know that I had run so far.”

“Yes.” Sarevan released him at last. “You are under your

father’s rule no longer. The Sunborn is emperor here.”

“That bandit. What is he to me?”

Hirel stopped. So one always said in Asanion. But this was

not the Golden Empire.

The Sun-priest showed no sign of anger. He only said, “Have

a care whom you mock here, cubling.”

“I will do as I please,” said Hirel haughtily.

“Was it doing as you please that brought you to the west of

Karmanlios in such unroyal state?” Sarevan did not wait for an answer. “Come,

cubling. The night is speeding, and you should sleep.”

To his own amazement, Hirel lay down as and where he was

told, wrapped in a blanket with only his arm for a pillow. The ground was

brutally hard, the blanket thin and rough, the air growing cold with the

fickleness of spring. Hirel lay and cursed this insolent oaf he had fallen

afoul of, and beat all of his clamoring pains into submission, and slid into

sleep as into deep water.

o0o

“Well, cubling, what shall we do with you?”

Hirel could barely move, and he had no wish to. He had not

known how sorely he was hurt, in how many places. But Sarevan had waked him

indecently early, droning hymns as if the sun could not rise of itself but must

be coaxed and caterwauled over the horizon, washing noisily and immodestly

afterward in the stream that skirted the edge of the clearing, and squatting

naked to revive the fire.

With the newborn sun on him he looked as if he had bathed in

dust of copper. Even the down of his flanks had that improbable, metallic

sheen.

He stood over Hirel, shameless as an animal. “What shall we

do with you?” he repeated.

Hirel averted his eyes from that proud and careless body,

and tried not to think of his own that was still so much a child’s. “You may

leave me. I do not require your service.”

“No?” The creature sat cross-legged, shaking his hair out of

its sodden braid, attacking it with a comb he had produced from somewhere. He

kept his eyes on Hirel. “What will you do, High Prince of Asanion? Walk back to

your brothers? Stay here and live on berries and water? Seek out the nearest

village? Which, I bid you consider, is a day’s hard walk through wood and

field, and where people are somewhat less accommodating than I. Even if they

would credit your claim to your title, they have no reason to love your kind.

Golden demonspawn they call you, and yellow-eyed tyrants, and scourges of free

folk. At the very least they would stone you. More likely they would take you

prisoner and see that you died as slowly as ever your enemies could wish.”

“They would not dare.”

“Cubling.” It was a velvet purr. “You are but the child of a

thousand years of emperors. He who rules here is the son of a very god. And he

can be seen unmasked even on his throne, and any peasant’s child may touch him

if she chooses, and he is not defiled. On the contrary. He is the more holy for

that his people love him.”

“He is an upstart adventurer with a mouthful of lies.”

Sarevan laughed, not warmly this time, but clear and cold.

His long fingers began the weaving of his braid, flying in and out through the

fiery mane. “Cubling, you set a low price on your life. How will you be losing

it, then? Back in Asanion or ahead in Keruvarion?”

Hirel's defiance flared and died. Hells take the man, he had

a clear eye. One very young prince alone and naked and shaven like a slave—if

he could win back to Kundri’j Asan he might have hope, if his father would have

him, if the court did not laugh him to his death.