The Modern Middle East (65 page)

Read The Modern Middle East Online

Authors: Mehran Kamrava

Tags: #Politics & Social Sciences, #Politics & Government, #International & World Politics, #Middle Eastern, #Religion & Spirituality, #History, #Middle East, #General, #Political Science, #Religion, #Islam

Figure 33.

A Palestinian woman inspecting the rubble of her house after Israeli missile strikes. Corbis.

Figure 34.

A Palestinian woman flashing the “V for victory” sign at Israeli soldiers. Corbis.

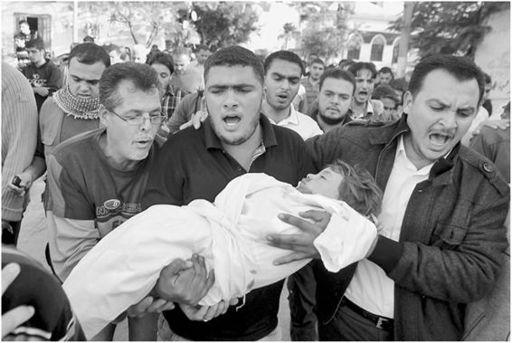

Figure 35.

Funeral of a two-year-old Palestinian boy killed in Israeli air strikes in the southern Gaza Strip town of Khan Yunis on November 15, 2012. Getty Images.

Within a week of the conclusion of the 2012 Gaza war, the UN General Assembly voted overwhelmingly to upgrade the status of Palestine to that of nonmember observer state, with 138 countries in favor, 9 opposed, and 41 abstaining. Jubilant crowds in Ramallah and other Palestinian cities celebrated what Mahmoud Abbas called “a birth certificate of the reality of the state of Palestine.”

123

But the fleeting street celebrations masked the desperate straits of the Palestinian cause. The Oslo Accords were long dead, and successive efforts to revive them had come to naught. A rehabilitated Benjamin Netanyahu, meanwhile, had made a comeback following his implication in a corruption scandal in the late 1990s and had become prime minister once again in February 2009. Neither the Likud nor any of its

coalition partners showed any appetite for meaningful progress of the peace process. After the Clinton administration, Presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama had also found themselves preoccupied with America’s wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, neither man showing the sustained political interest or the courage needed to force the Israelis and the Palestinians to the negotiating table. With the peace process adrift, and Palestinian frustrations mounting over the ever-expanding size of Israeli settlements, upgraded diplomatic recognition at the United Nations was more than anything else an act of desperation on the part of the Palestinian Authority. At any rate, the importance of the UN vote was far more symbolic than substantive. Israel, for its part, duly retaliated by withholding more than $100 million in tax revenues from the cash-strapped PNA. More ominously, it announced plans for the construction of as many as 6,600 new housing units in settlements in the West Bank, including in East Jerusalem.

124

Once the settlement expansions are completed, they will effectively cut the West Bank in two. In the words of Ban Ki-moon, the secretary-general of the United Nations, this move “gravely threatens efforts to establish a viable Palestinian state.” Ban’s “call on Israel to refrain from continuing on this

dangerous path,” joined by similar refrains from some of Israel’s erstwhile allies, were all ignored.

125

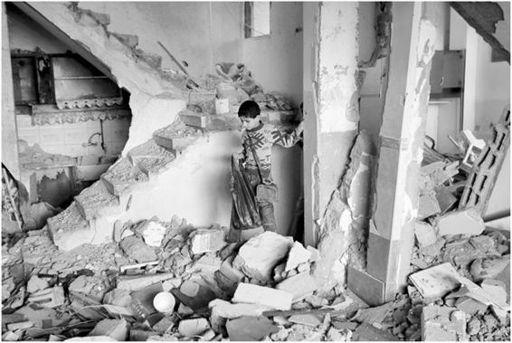

Figure 36.

A Palestinian boy walking through the rubble inside the house of Hamas commander Raed al-Attar, which was targeted by an overnight Israeli air strike in the southern Gaza Strip town of Rafah on November 20, 2012. Getty Images.

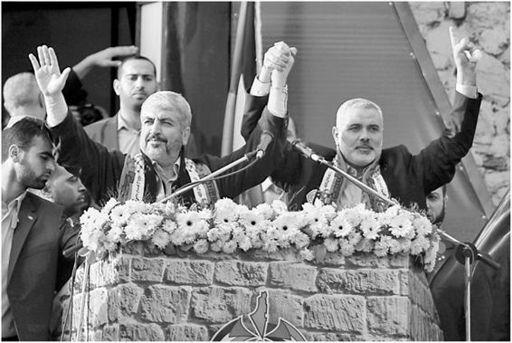

Figure 37.

Hamas leader in exile Khaled Meshaal (left) and Hamas prime minister in the Gaza Strip Ismail Haniya (right) at a rally to mark the twentyfifth anniversary of the founding of the Islamist movement, in Gaza City on December 8, 2012. Getty Images.

As of this writing, the conflict between the Israelis and the Palestinians shows no signs of a resolution. Different solutions for a peaceful end to the conflict continue to be offered by old actors and even new ones, including Saudi king Abdullah and the Quartet on the Middle East (composed of the United States, the United Nations, the European Union, and Russia). For a region racked by more than a century of war and bloodshed, the need for a lasting peace has never been greater. For now, however, the prospects of such a peace seem painfully remote. Hamas and the Fatah, meanwhile, have fragmented the Palestinian body politic in ways that Israel could not have dreamt of. With friction and animosity characterizing intra-Palestinian relations, it is not surprising that meaningfully ending the Palestinian-Israeli conflict seems today like a distant dream.

Despite repeated setbacks and the seeming futility of the never-ending “peace process,” monumental progress has indeed been made over the years on several fronts in relation to certain specific aspects of the conflict. As we have seen so far, this is a conflict whose very essence has been

shaped and reified by the blood, sweat, and tears of the antagonists on either side. The fault lines run too deep, the responses are too visceral, and the stakes are too high for there to be any easy solutions, or perhaps

any

lasting solutions at all. But to dismiss all efforts toward peace as hopeless and futile would be at best ignorant of what has been accomplished so far and at worst fatalistic and resigned to an absence of peace. Despite its flaws and go-it-alone character, the Camp David Accord did return the Sinai to Egypt and led to an Israeli-Egyptian peace that has lasted since 1978. The Oslo Accords, for their part, though maligned and ignored soon after their signing, brought about the institutional ingredients and an actual, albeit truncated, territorial frame of reference that are key elements in the eventual construction of a state. And, the second Camp David summit, held in July 2000, crossed some of Israel’s most firmly drawn red lines by having the Jewish state’s prime minister offer to put up for negotiations the status of Jerusalem and the right of Palestinian refugees to return home and be reunited with their families. As the scholar Avi Shlaim has put it, “The mere fact that . . . the core issues of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict were discussed at all is significant. Jerusalem is no longer a sacred symbol but the subject of hard bargaining. The right of return of the Palestinian refugees is no longer just a slogan but a problem

in need of a practical solution. A final status agreement eluded the negotiators, yet everything has changed.”

126

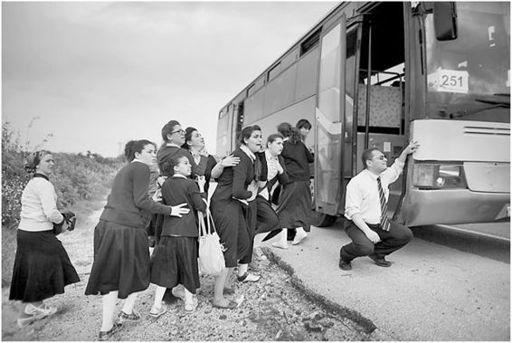

Figure 38.

Israeli schoolgirls taking cover next to a bus in Ashdod, Israel, during a rocket attack from the Gaza Strip, on March 12, 2012. Getty Images.

By the accidents of history and geography, the two peoples of Palestine and Israel found themselves on the same piece of land. Each side has tried to stake a claim for its right to control the land. The ensuing conflict has been not just a dialogue of the deaf but a brutal, violent struggle to destroy or at least dehumanize and demonize the enemy, to take away its spirit and its life. In some ways, the passage of time has forced the antagonists to face the sobering realities of the conflict. But the wounds of the past are too fresh and the memories of historic wrongs remain too deep to allow either side to trust the other. The oscillating preferences of the Israeli electorate in the past few elections reflect their unease and uncertainty over the wisdom of finally embracing the enemy. The same dilemma exists for the Palestinians, who are equally torn between the rejectionism of Hamas and the Islamic Jihad and the relative moderation of an increasingly beleaguered and ineffectual PNA. This popular anguish manifested itself in the form of the

intifadas.

For all their mutual hatred and distrust, the Arabs and Israelis in general and the Palestinians and Israelis in particular have managed to travel far on the road to peace. The Camp David Accords of 1978 resulted in a peace between Israel and Egypt that has so far lasted for more than three decades. Despite frequent frictions and disagreements, the Egyptian-Israeli peace shows no signs of collapse, even after the 2012 election of the Muslim Brotherhood’s Mohamed Morsi to the presidency of Egypt. In the same way, the 1993 Oslo Accords brought the historic adversaries together and, at the very least, made each party realize that “the enemy” does indeed have a face, a family, human emotions, and, most important, a right to exist. Many on both sides still deny this basic right, but their denials can no longer be backed by empirical data. Reality, the “facts on the ground,” may be subject to different interpretations, but it cannot be denied. Israelis and Palestinians exist, and despite their best efforts at destroying each other, neither side shows signs of simply vanishing.

In one important respect, the tangible progress made so far on the issue of Palestinian-Israeli peace has made it harder for would-be Nassers or Khomeinis, and other self-declared liberators of Palestine, to claim Palestinian leadership. Alas, there has been no shortage of liberationists in the Middle East, and future Qaddafis and Saddams may still appear. Soon after it started, the struggle between Palestinians and Israelis became known as the “Arab-Israeli conflict,” and now, after many decades and

many wars, it has once again become more of a Palestinian-Israeli conflict. Ultimately, the two peoples need to resolve their conflict themselves, although, as with any other passionate arguments, third-party mediations often help.

History is both written and directed by victors, and how the Israeli-Palestinian question finally gets settled depends on who holds which trump cards. Edward Said warned of the permanent ghettoization of the Palestinians and the establishment of a two-tiered, apartheid-like state, whereby Israeli dominance would be ensured by the complicity of a self-serving PNA.

127

Aharon Klieman, a respected, liberal Israeli academic, envisions two peoples that are “separate but dependent” as a realistic (and desirable) outcome. Perhaps, he argues, there could even be some type of a confederation between the three otherwise small entities of Palestine, Israel, and Jordan.

128

These are, at best, all conjectures. For now, the future is far from certain; but it is clear that the peoples of Israel and Palestine must learn to share the same piece of land.