The Modern Middle East (67 page)

Read The Modern Middle East Online

Authors: Mehran Kamrava

Tags: #Politics & Social Sciences, #Politics & Government, #International & World Politics, #Middle Eastern, #Religion & Spirituality, #History, #Middle East, #General, #Political Science, #Religion, #Islam

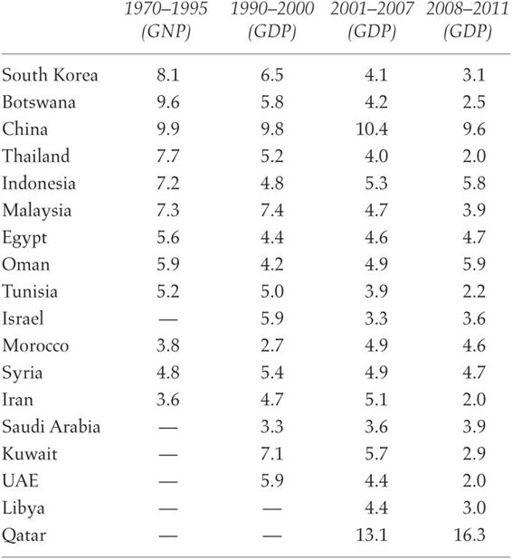

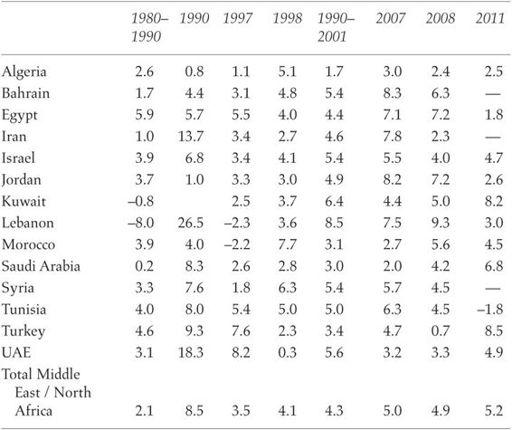

Despite the pervasiveness of statism, extensive state intervention in the economy has failed to have the desired developmental effects in the Middle East. While brisk in the 1960s and especially in the 1970s, thanks to dramatic rises in oil revenues, the overall rate of economic growth in the Middle East over the past few decades—as measured by annual growth rates in the gross domestic product—has not been outstanding compared to that in other regions of the developing world (tables 5 and 6), even though oil prices exploded in 1973–74 and then briefly rose again in the late 1970s. When oil prices collapsed and the region experienced a general recession from 1985 to 1995, most Middle Eastern countries witnessed severe economic reversals. Only after 2000, when oil prices rose steadily before their spectacular collapse in 2007, did most Middle Eastern countries experience impressive rates of growth. Overall, the annual growth rate of the gross domestic product (GDP) in the Middle East and North Africa was nearly halved, from 8.5 percent in 1990 to 3.5 percent in 1997, before recovering to 5.2 percent in 2011. As table 6 demonstrates, the reversals were steep in Bahrain, Egypt, Iran, Jordan, Lebanon, and Tunisia. Turkey and the United Arab Emirates also experienced declines in their GDP in the mid-2000s, although they appear to have recovered by the late 2000s. Again, only

significant increases in the price of oil helped the region’s economies in the early to mid-2000s.

Table 5.

GNP and GDP Average Annual Growth Rate in Developing Countries

SOURCE:

World Bank, Development Indicators Database, “GDP Growth (Annual %),”

http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD.ZG

.

Statism brought with it largely stagnant economies. This stagnation resulted from a combination of factors. To begin with, these economies have been run by highly bloated and inefficient bureaucracies that continue to be mired in red tape, corruption, and nepotism. In every country in the Middle East, corruption was, and remains, a pervasive obstacle to substantive economic development.

22

The problem of “urban bias” and the preference for industrial development over agriculture have led to a near-total neglect of rural areas. This has resulted in increasing levels of dependence on agricultural imports and an exodus of rural migrants into the cities. The region’s aridity and water scarcity have not helped agricultural development. Even

in Egypt, where agricultural output showed some modest increases—2.9 percent annually in 1960–70, 3.0 percent in 1970–80, 2.6 percent in 1980–89, and 4.5 percent in 1991–2000—such gains could hardly keep pace with the growth of the population (see chapter 11). Additionally, levels of agricultural production are kept in check by patterns of land ownership and land use that often resist technological improvements and efficiency.

23

In Saudi Arabia, in the 1980s and 1990s the government pumped millions of dollars into expanding agricultural output both through direct investments and through massive subsidies and other incentives given to private farmers.

24

However, the country’s harsh climate and inefficient farming practices undermined the possibility of profitable yields, and the program was eventually abandoned.

Table 6.

Growth of GDP in Selected Middle Eastern Countries, 1980–2011

SOURCE:

World Bank, Development Indicators Database, “GDP Growth (Annual %),)

http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD.ZG

.

Besides bureaucratic red tape and neglect of agriculture, statism had other structural limitations that severely inhibited industrial development

on a national scale. Consumer prices continuously rose, forcing many states to embark on extensive subsidization programs for basic foodstuffs and other essential items. Despite overwhelming attention to industrial development, domestic industry was hardly competitive internationally, and, if given a choice, consumers frequently preferred foreign products over domestic ones. Most industrial enterprises also operated at far below capacity. Industrial imports remained consistently high, therefore, as domestic industry lagged behind in quality and caliber of production.

25

The state’s attention to heavy industries—steel mills, power plants, automobile assembly plants, and the oil sector—also impeded the emergence of nationwide industrial linkages, resulting in the underdevelopment and inefficiency of various other sectors of the economy, such as banking, insurance, construction, and transportation. The state then had to either fill the ensuing gaps itself or turn to foreign enterprises to do so, thus contradicting its own ideological justifications for economic intervention. Inadequate planning and lack of sufficient technical and administrative resources only exacerbated the situation. The difficulties experienced by Algeria in many ways mirrored those experienced by other states of the Middle East: “As pressures grew to meet unrealistic targets, the central planning office and the larger state corporations were frequently overwhelmed by the magnitude of their tasks. Programs were subject to long delays and escalating costs. State corporations let contracts to foreign companies to build complex turnkey enterprises, which greatly increased development costs and at the same time created new dependency on foreign suppliers and expertise. The avoidance of such dependency had been one of the primary goals of the national economic strategy. The process also stamped the emerging industrial infrastructure with a technological incoherence that inhibited integration.”

26

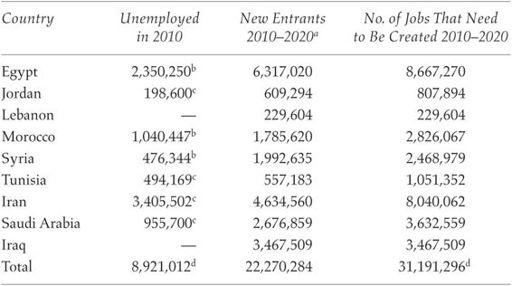

At the same time, states proved woefully incapable of providing adequate employment opportunities for new entrants into the job market, resulting in chronic unemployment and underemployment, especially of the youth. Those who could, migrated to the oil monarchies of the Persian Gulf—especially to Kuwait, Qatar, and the UAE—but in most cases such migrations were temporary and did not address structural economic shortcomings in the sending countries. As table 7 indicates, current and future employment prospects are particularly bleak in countries such as Morocco, Tunisia, Egypt, Syria, Iran, Iraq, and Saudi Arabia, where millions of new jobs need to be created for new job seekers every year. According to the World Bank, countries in the Middle East and North Africa needed to create one hundred million jobs between 2000 and 2020 in order to absorb the unemployed and new entrants to the market.

27

Table 7.

Number of Jobs That Need to Be Created in Selected Middle Eastern / North African Countries (2010–20)

a

Equals total labor force in 2020 minus total labor force in 2010. International Labor Organization, LABORSTA database, 6th ed., October 2011, “Economically Active Population, Estimates and Projections,” “Data for All Countries by 5 Years Age Groups and Total (0+ and 15),”

http://laborsta.ilo.org/applv8/data/EAPEP/eapep_E.html

.

b

Equals total men and women unemployed in 2010 (averaged quarterly data for that year). International Labor Organization, LABORSTA database, “Unemployment,” “Main Statistics (monthly): Unemployment General Level,” col. D13,

http://laborsta.ilo.org/

.

c

Equals unemployment rate times population in labor force. Unemployment rate data from International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook Database, “Unemployment Rate (% of Total Labor Force” data for population in labor force from International Labor Organization, LABORSTA database, 6th ed., October 2011, “Economically Active Population, Estimates and Projections,” “Data for All Countries by 5 Years Age Groups and Total (0+ and 15),”

http://laborsta.ilo.org/applv8/data/EAPEP/eapep_E.html

.

d

These figures exclude 2010 unemployment data from Lebanon and Iraq.

Not surprisingly, pressures for economic reforms mounted throughout the 1980s. Cost-of-living riots had occurred in Morocco in 1965, 1982, and 1984; in Tunisia in 1978 and 1984; in Egypt in 1977; in Sudan in 1985, acting as a catalyst for a successful military coup; in Algeria in 1988; and in Jordan in 1989.

28

For countries such as Turkey, Algeria, Egypt, Jordan, Tunisia, and Morocco, additional pressures were exerted by international lenders such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, which had helped finance various development projects and thus had some leverage over domestic state actors. For other countries, such as Syria and Iran, which either had largely avoided World Bank loans (Iran) or did not care about the pressure to repay them (Syria), much of the impetus for reforms came from within.

29

After decades

of revolutionary promises, it was time for the state to start delivering. Even in Syria and Iran the population was getting restless.

In the late 1980s and the 1990s, “structural adjustment programs” became the new buzzword among Middle Eastern economic policy makers. Turkey, Iran, Egypt, Jordan, Tunisia, Algeria, and Morocco promised to implement especially ambitious reform packages. But only Turkey, Tunisia, and Morocco have made significant strides toward implementing meaningful reforms aimed at disentangling the many tentacles of the state from the economy.

30

In most of the region’s other countries, the need for extensive economic reforms seldom moved from debate and deliberation to implementation. According to the World Bank, by 2001, in the Middle East and North Africa as a whole, investments in infrastructure projects with private participation—projects in telecommunications, energy, transport, and water and sanitation—remained largely negligible as compared to the rest of the world.

31

As we saw in chapter 8, when the state did sell some of its assets, such as hotels and insurance and telephone companies, those sales often went to close associates or family members of the president, thus encouraging a culture of crony capitalism without significant consequences for urban middle-class entrepreneurs. Throughout the region, in fact, private sector development still has a long way to go and is often victim to a state that is reluctant to relinquish any measure of control or ownership. Not surprisingly, the state continues to be the dominant actor in the economy.

The reasons for the slow pace of economic liberalization are both political and economic. Economically, private savings are often much too small to make the purchase of state-owned enterprises possible without powerful political connections. Also, most governments are reluctant to sell off unprofitable enterprises at below-market prices, but neither do they have the resources necessary for making such enterprises profitable again. Moreover, the state is often reluctant to sell to foreign buyers and investors, especially since such sales may spark adverse nationalist reactions among the populace.

32