The Modern Middle East (61 page)

Read The Modern Middle East Online

Authors: Mehran Kamrava

Tags: #Politics & Social Sciences, #Politics & Government, #International & World Politics, #Middle Eastern, #Religion & Spirituality, #History, #Middle East, #General, #Political Science, #Religion, #Islam

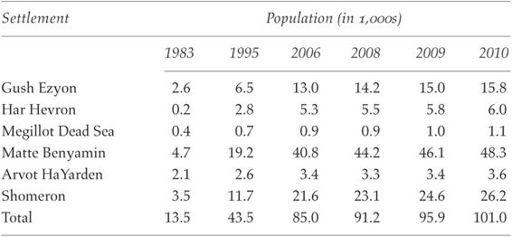

Table 4.

Population Growth in Selected West Bank Settlements

SOURCE:

Central Bureau of Statistics of Israel, “Localities and Population, by Municipal Status and District,” table 2.13 in

Statistical Abstract of Israel, 2009

(Tel Aviv: Government Publishing House, 2010) and

Statistical Abstract of Israel, 2011

(Tel Aviv: Government Publishing House, 2012).

Settlements represent more than mere demographic colonization of the Occupied Territories by Israel. They signify a

deepening

of Israeli control over the territories and their Palestinian residents. In addition to expanding Israeli military control, settlements are designed to facilitate Israel’s access to two additional, strategic resources: land and water. An elaborate road system has been constructed to link Israel directly to the new settlements while bypassing major Arab towns in the West Bank such as Nablus and Ramallah. According to Israel’s Central Bureau of Statistics, the number of new settlement dwellings sold in the West Bank jumped from 437 in 2006 to 733 in 2008.

66

New settlements and housing units bring with them additional Israeli infrastructure and military patrols—in addition, of course, to heavily armed settlers—thus solidifying the extent and nature of Israeli

control. The Palestinian city of Hebron, while an extreme example, starkly demonstrates this point: “Because Hebron is the only city in all of the West Bank where Jews actually live among the Arabs—as opposed to living in self-contained settlements near Arab towns—the Israelis have retained control over 20 percent of the city so they can protect the 540 Jewish residents. However, 20,000 of Hebron’s 125,000 Arabs . . . live or work in the area still under Israeli control.”

67

Hebron’s settlers, it must be pointed out, are “ideological” or “political” settlers who have moved into predominantly Palestinian areas mainly to “establish facts on the ground.” Initially, all settlement activities were ideological and were orchestrated by a fundamentalist group calling itself the Gush Emunium (Bloc of the Faithful).

68

In recent years, relatively inexpensive property prices have drawn an increasing number of nonideological bargain hunters motivated by convenience, especially in light of the preferential treatment they receive from the government when it comes to “the provision of space, construction, water provision and grants.”

69

Today, nearly 60 percent of all settlers are nonideological Israelis in search of hilltop properties at affordable prices.

Ideological settlers at times resort to violence against Palestinians. According to BʾTselem,

Acts of violence carried out by settlers against Palestinians and Palestinian property are an ongoing and widespread phenomenon. In recent years, some of these acts have been referred to as “price tag attacks”—a response to actions of the Israeli authorities that are perceived to harm the settlement enterprise. For example, some of the attacks occurred after the Military’s Civil Administration distributed demolition orders for settlement structures that were built unlawfully, or after such structures were demolished. In other cases, the violence took place after Palestinians harmed settlers. Security forces do not always deploy in advance to protect Palestinians from settler violence, even when such violence could be anticipated.

70

In addition to depopulation and repopulation, Israel has sought to control the Occupied Territories by marginalizing and incapacitating them economically and politically. The political incapacitation of the territories, in the form of tight controls and the imposition of measures that are all too often draconian, was alluded to earlier. Complementing these political-military measures have been specific policies designed to ensure the continued economic underdevelopment of the West Bank and Gaza. Occupation policies, and restrictions on construction activities or the physical movement of people, have resulted in the underdevelopment or complete absence

of industrial, construction, and service sectors throughout the territories, so that small-scale agriculture remains one of the most common forms of economic activity. Nevertheless, poverty remains prevalent among Palestinians.

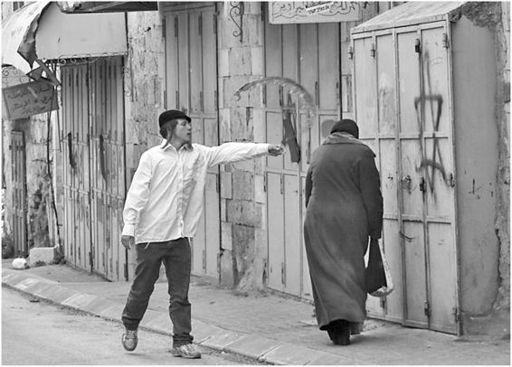

Figure 29.

A settler tossing wine at a Palestinian woman on Shuhada Street in Hebron. Corbis.

The economic dependence of the territories on Israel is further deepened by Israel’s ability to literally close off the territories to through traffic. The road system, as already mentioned, reinforces the segmentation of the Palestinian economy and impedes economic integration and development. Attempts at slowing the pace of Palestinian economic development can also take more direct and blatant forms. On many occasions, for example, Israeli authorities have prevented fishermen and agricultural producers from Gaza and the West Bank from harvesting their crops or exporting them in a timely manner as needed.

71

As a result, both Gaza and the West Bank, especially the former, have consistently suffered from crushing poverty. According to the World Bank, the Palestinian per capita gross domestic product (GDP) in 2006 ($1,130) was 40 percent less than what it was in 1999. In 2012, some 22 percent of Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza lived below the national poverty line. Poverty was nearly twice as high in Gaza as in the West Bank (33 percent

versus 16 percent), and “deep poverty,” measured by how far below the poverty line one falls, was also twice as high in Gaza as in the West Bank.

72

Unemployment in both territories has also been persistently high, peaking at around 30 percent in 2002 before coming down somewhat to just below 24 percent in 2010. Palestinian youth unemployment remains a particular problem, averaging around 35 percent, in Gaza having reached a staggering 53 percent by the end of 2010.

73

Collectively, these are the conditions within which the two

intifadas

took place. For the thousands of young Palestinians who have taken part in the uprisings, life has held little promise. Their days have been defined by threats and intimidation, discrimination, poverty, and despair. Under conditions in which access to health care and garbage collection seemed like unattainable luxuries, the Palestinians’ frustrations turned them into stone throwers in the late 1980s and the early 1990s, and, as the violence escalated, into suicide bombers in the late 1990s. Like all spontaneous revolutions, the two

intifadas

developed their own logic and momentum, their own symbols, martyrs, and leaders. They also gave ample opportunities to those bent on unleashing indiscriminate terror on the Israelis, and many innocent bystanders were killed as a result.

74

The second

intifada,

also known as the Al-Aqsa

intifada,

was especially violent. According to the U.S. Department of State, in 2002 an estimated 469 Israelis were killed and over 2,498 were injured as a result of more than sixty Palestinian suicide bombings.

75

From the beginning, the

intifada

’s mass-based, popular nature made it virtually impossible for the Israeli army to contain. In desperation, in the late 1980s the Israeli government turned to its archenemy, the PLO, which had itself become greatly weakened and was desperate to reassert its control over the full-fledged rebellion. In the process, the PLO hoped also to reinvigorate its ties with its constituency. By now, the sheer scope of the uprising and the gravity of the Israeli government’s response had made many ordinary Israelis question the wisdom of their country’s continued hold on the Occupied Territories. The alternative to peace, it seemed, was too costly, too brutal, and too much at variance with the original goals of Zionism. Somehow the madness needed to be stopped. Peace appeared as the most viable and attractive solution to the quagmire that the Occupied Territories had become.

The conflict between the Israelis and the Palestinians had been raging for nearly a century. At least four wars had been fought, tens of thousands of

people had been killed on both sides, and countless lives had been shattered. The accumulated human and emotional costs of the conflict can be fully grasped only by the Israelis and the Palestinians who bore them. One land, two peoples—that’s how it all started. In the process, each side degenerated into “the enemy” of the other. Eager to defend their survival and right to exist, both sides all too often lost perspective and compromised their own humanity. Wars numb the senses, blur the distinction between right and wrong, and confuse means and ends. The conflict over Palestine/Israel was approaching the century mark, and it was only a matter of time before each side realized what it had become. Such was the realization of some, but by no means all, Israelis and Palestinians.

The imperative of peace making was not so much a sudden epiphany by the actors involved as the product of a larger historical evolution of the conflict. Over time, a group of Palestinians and Israelis had come to realize that they could not deny the existence of the other, no matter how hard they tried or what weapons they used. They were also troubled by the increasing inhumanity to which the conflict had given rise—not only the enemy’s inhumanity but also their own. On each side of the divide there thus developed a group of “accommodationists” who gradually became convinced of the need to accommodate the other side and recognize its right to exist. Idealists willing to compromise with and accommodate the enemy had always existed on both sides. However, their voices had been drowned out by a majority righteously bent on the total destruction of the enemy. But the seven-year

intifada,

which had turned into the longest sustained battle between Palestinians and Israelis, drove home the costs of war for more Palestinians and Israelis. The 1967 War had lasted only six days and the 1973 War only a few weeks. But the

intifada

opened people’s eyes to the sobering realities of war: home demolitions, suicide car bombs, mass deportations, abject poverty, despair, fear and paranoia, stabbings, and a host of other tragedies unfolding before the eye day after day. In the words of two Israeli scholars, “The violence also deeply affected Israel itself. Many Israelis perceived their country’s occupation as morally indefensible, social--ly deleterious, economically ruinous, and politically and militarily harmful. Israel’s political leadership faced mounting pressures from broad segments of the public to stop quelling the uprising by force and instead to propose political solutions.”

76

A similar process was also occurring among Palestinians, for whom the costs of the

intifada

were even more immediate and devastating.

By 1992, the leaders of the state of Israel—notably Foreign Minister Shimon Peres and Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, who had done long service

in the military—had become convinced of the necessity of peace. Earlier, when he had been the defense minister, Rabin had tried desperately to stop the

intifada

but to no avail. Peace, he must have reasoned, was the only viable alternative. With the larger “accommodationist” trend growing among many Israelis, he could now sell his vision of the future to a larger audience. This vision, incidentally, was articulated most idealistically by Shimon Peres.

77

The PLO, meanwhile, exiled in Tunis and despondent over its inability to fully control the

intifada

and the activities of those “inside,” saw accommodation with Israel as the only way to salvage its continued political viability and its relevance for the Palestinians. The PLO’s shift in strategy was welcomed by many Palestinians, who were elated at the prospect of finally living in peace.