The Modern Middle East (25 page)

Read The Modern Middle East Online

Authors: Mehran Kamrava

Tags: #Politics & Social Sciences, #Politics & Government, #International & World Politics, #Middle Eastern, #Religion & Spirituality, #History, #Middle East, #General, #Political Science, #Religion, #Islam

These domestic political considerations had prompted Sadat to embark on an ambitious diplomatic campaign almost immediately after taking office. His principal aim was to secure some territorial concessions in the Sinai from Israel. Most of these efforts occurred first through the United Nations and then through the United States, whose active diplomacy had finally brought an end to the 1969–70 War of Attrition. The War of Attrition had started in March 1969, when the Egyptian army launched a large-scale assault on Israeli forces occupying the Suez Canal. Nasser’s intent was to prevent Israel from turning the canal into a de facto border

with Egypt, to increase for Israel the costs of Sinai’s occupation by making it suffer steady losses in soldiers and equipment, and, eventually, to force it to withdraw to the pre-1967 border. To achieve these goals, with his armed forces gradually rebuilt by the Soviets, he resorted to the heavy bombardment of Israeli defenses, accompanied by occasional air strikes and mobile commando raids. The war dragged on through the spring and summer months inconclusively, interrupted only by an unsuccessful attempt by the United States to broker a cease-fire. The American initiative was rejected by the Israeli government, which in early 1970 decided to take the war to the Egyptian hinterland by starting aerial bombardments of Cairo’s suburbs. Finally, in August 1970, following extensive military and economic assurances by the Nixon administration, the Israeli prime minister, Golda Meir, agreed to end the war that Nasser had started.

The War of Attrition formed the backdrop against which Sadat’s diplomacy in the early years took shape. Despite its inconclusiveness, many in the Israeli cabinet considered Israel to have been the real victor in the latest military conflict with Egypt. From a strategic standpoint, although Soviet help to Egypt had reduced Israel’s near dominance of the skies, Egyptian forces had made little or no tangible progress in their costly, eighteen-month confrontation with the IDF. Considering the Jordanian civil war and Nasser’s subsequent death in September 1970, Golda Meir viewed the Arab bargaining position as too weak to merit negotiations. More could be achieved, she reasoned, by a “diplomacy of attrition,” in which Israeli intransigence would eventually lead to the signing of a comprehensive peace treaty with Egypt.

53

So early in his career, and with the Sinai still occupied, Sadat was in no position to sign a comprehensive peace treaty with Israel. For now, his immediate goals were to see the Suez Canal opened, thereby restoring to Egypt one of its most vital economic lifelines, and, if only as a symbolic gesture, to station some Egyptian troops on the canal’s east bank. Mistrustful of Sadat’s real motives, Meir and other hard-liners in her cabinet opted instead to strengthen Israel’s hold over the West Bank and Gaza by encouraging the building of more settlements and factories in Palestinian areas.

Sadat declared in a broadcast to the nation, “1971 will be the Year of Decision, toward war or peace. This is a problem that cannot be postponed any longer. We have prepared ourselves from within, and we ought to be ready for the task lying ahead. . . . Everything depends on us. This is neither America’s nor the Soviets’ war, but our war, deriving from our will and determination.”

54

But the “year of decision” came and went with no tangible results. Always with a flair for the dramatic, Sadat had to make good

on his rhetoric sooner or later, either through diplomacy or on the battlefront. True to form, the Egyptian president did not disappoint. In July 1972, he abruptly expelled the estimated fifteen thousand Soviet advisers who were helping Egypt rebuild its armed forces after their destruction in 1967. He also broke off relations with Jordan over a relatively minor pretext—a proposal by King Hussein to form a Jordanian federation with sovereignty over Palestinians. Golda Meir and many of the hard-liners in her cabinet interpreted these developments as further signs of the Egyptian president’s weakened strategic and military position. Surely the Egyptians, who had been so decisively routed back in 1967, could not pose a serious threat to Israel now that they had lost their Soviet patrons and Jordanian allies! The reality was quite different, however. Sadat’s expulsion of Soviet military advisers and diplomatic row with Jordan were actually intended to give him a freer hand in waging war on Israel.

The war came on October 6, 1973, in the middle of the Muslim holy month of Ramadan and the Jewish Yom Kippur.

55

In a brilliantly coordinated and executed blitz, at 2:00

P.M.

Syrian and Egyptian forces attacked and in a few hours overran Israeli defensive positions in the Golan and the east bank of the Suez, respectively. On the Sinai front, the attack featured some seven hundred Egyptian tanks. By nightfall, under a barrage of artillery fire, the Israeli defensive fortification known as the Bar-Lev Line—named after its creator, Lt. Gen. Chaim Bar-Lev—had been breached. Helped by the latest bridge-building technology from the Soviet Union and their own ingenuity and drive, Egyptian personnel and artillery units were ferried over to the east bank of the Suez by the hundreds, and Egyptian commandos were airlifted deep into the Sinai to attack and destroy Israeli command and communications facilities. Israel’s losses on the Syrian front were even more dramatic: by the end of the first day’s fighting, the entire Golan Heights had been recaptured by Syrian forces. In its initial efforts to prevent the Syrians from gaining further ground, the Israeli air force lost some forty aircraft in the first few days of the conflict. An Israeli counterattack in the Sinai, which resulted in the one of the biggest tank battles since World War II, also failed to dislodge the Egyptians from the Suez. For the first three days, up until October 9, it appeared as if the Syrian and Egyptian forces were assured of victory.

The course of the war shifted dramatically in Israel’s favor thereafter. Before the remainder of the war is examined, a few words need to be said about the reasons behind the Arab armies’ initial stunning victories. Broadly, these can be divided into three sets of developments. By far the most significant was the increasing professionalization of the Egyptian and

Syrian armies in the years following the June 1967 War, resulting from the purging of incompetent commanders, a strengthening of discipline through the ranks, and greater familiarity with the available Soviet weaponry.

56

Equally important was the overconfidence of the Israelis, who, continuing to perceive Arab military capabilities in 1967 terms, saw the Arabs as overly boastful, incompetent, incapable of handling their sophisticated Soviet weaponry, and easily frightened.

57

The chronic political instability in Syria and Sadat’s image problems at home and abroad did little to change the general Israeli view of the Arabs’ predicament. Last were a number of strategic and tactical considerations. The Israelis did not think the Arabs would attack during Ramadan, when observant Muslims fast, and certainly not in broad daylight. Therefore, only a skeletal force was defending the Bar-Lev Line, most others being on leave to celebrate Yom Kippur.

58

The Israelis were also unfamiliar with the Egyptians’ new equipment, such as rocket launchers carried in small suitcases, high-powered water pumps to puncture holes in defensive walls, and light ladders for scaling walls. This was an entirely different war from the one seven years earlier.

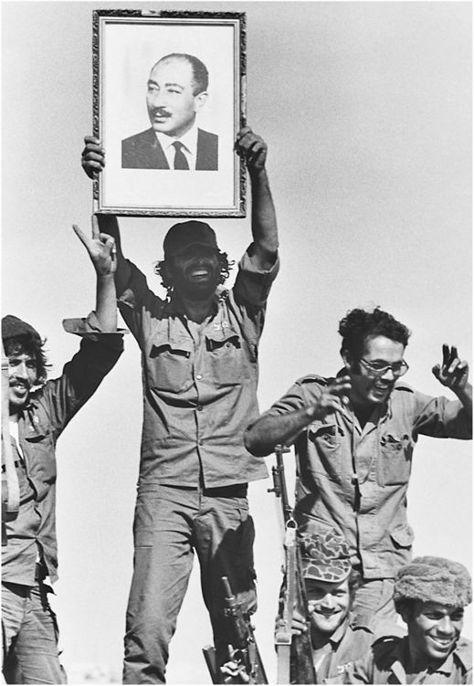

Figure 10.

Egyptian soldiers celebrating the crossing of the Suez Canal in the 1973 War. Corbis.

The tide of the war turned for two primary reasons. The first concerned war psychology and its tactical consequences. Apparently both the Syrian and Egyptian forces were stunned by the ease with which they had overrun Israeli forces and had not really planned on what to do once they had recaptured lost territory. Conversely, the Israelis soon overcame the shock of the collapse of their forces and regrouped. One of the most spectacular episodes of the war occurred on the night of October 15, when the IDF’s Major General Ariel Sharon led a small force of Israeli commandos across the Suez and inflicted heavy casualties on Egyptian forces.

But such daring tactical moves would not have been possible had it not been for a second factor, the massive airlift of military equipment and supplies to Israel by the United States. Everything from tanks to aircraft was rushed to Israel from aircraft carriers belonging to the U.S. Sixth and Seventh Fleets, some directly from military bases in the United States, and the equipment was put to use within hours of delivery.

59

According to one military analyst, “In replacing Israel’s downed aircraft, the United States literally stripped some of its own active air force units,” sending forty F-4 jet fighters to Israel and leaving its own air defense system vulnerable for six months.

60

By the third week of October, the Arab position had become untenable. The Syrians had been evicted from the Golan again, and Israel’s campaign to destroy the Syrian economy was having devastating consequences. Syria’s only oil refinery, in Homs, was set ablaze by Israeli jets, and the ports of

Banisa, Tartus, and Latakia were heavily damaged. Damascus itself was being threatened by Israeli forces. In the Sinai, meanwhile, Israel’s counterattack was beginning to bear fruit, to the point that by October 17 the Egyptian Third Army was encircled and in serious danger of annihilation. Meanwhile, U.S. secretary of state Henry Kissinger had embarked on his famous “shuttle diplomacy,” flying from one capital to another in search of a cease-fire agreement. On October 22, the UN Security Council adopted Resolution 338, calling for an immediate secession of hostilities, the implementation of Resolution 242 of 1967, and the start of peace negotiations under international auspices. Egypt and Syria readily agreed to the resolution; Israel did not cease hostilities until a further resolution was passed on October 23.

Conspicuously absent from the October 1973 War was Jordan. By some accounts, Sadat and Syrian president Hafiz al-Assad had deliberately kept King Hussein in the dark regarding the details of their plans to jointly attack Israel.

61

Jordan’s small army and its long border with Israel made the country’s participation in the war very risky for the king. Sadat had informed King Hussein of his military plans as early as spring 1973, but the Jordanian monarch remained skeptical of the chances of success of even a limited attack on Israel. “It is clear today that the Arab nations are preparing for a new war,” the king wrote to his generals in May. “The battle would be premature.”

62

Nevertheless, as a token of his support for the Arab cause, the king dispatched an armored brigade to Syria, although there was no military significance to such a move. Iraq’s contribution to the war was somewhat more meaningful, at least in theory, with the participation of a squadron of twelve Iraqi MiG fighters beginning on October 8. Of the twelve fighters, half were mistakenly shot down by Syrian gunners and the other half were destroyed by the Israelis.

63

In military and territorial terms, the 1973 War, unlike the 1967 conflict, did not result in a transfer of large parcels of land or the decisive victory of one side over the other. But the war had deep and lasting consequences for all the parties involved in the Arab-Israeli conflict. The fallout from the war not only influenced the domestic politics of each of the actors in the conflict but had wider regional and international ramifications. Egypt and Israel were the most profoundly affected, but so were the PLO and the larger Arab world. Also, a new factor entered the international political economy of the Middle East and that of the entire world: oil.

The consequences of the 1973 War appear to have been greatest for the life and politics of Egypt. “The Ramadan War” was Sadat’s war, conceived, coordinated, and carried out under his leadership. By bringing the IDF to the verge of defeat, Sadat had done what Nasser had tried but had miserably

failed to accomplish. Sadat had now quieted the skeptics, and had done so with authority. Standing tall shortly after the war, Sadat declared, “The Arab armed forces performed a miracle in the Ramadan War as judged by any military measure. The Arab world can rest assured that it has now both a shield and a sword.”

64

Indeed, as three Egyptian generals later wrote triumphantly in

The Ramadan War,

the twin myths of Israeli invincibility and Arab incompetence were both shattered.

65

After all, Israel, which had so decisively obliterated the Arab air forces on the ground in 1967, had now lost a total of 115 aircraft.

66

Israel might not have been defeated, but as far as the Egyptians were concerned, victory was theirs. A new pharaoh had emerged, a man who had finally ended the Arabs’ collective shame and humiliation. Sadat could now add a new moniker to his name: “The Hero of the Crossing.”