The Modern Middle East (23 page)

Read The Modern Middle East Online

Authors: Mehran Kamrava

Tags: #Politics & Social Sciences, #Politics & Government, #International & World Politics, #Middle Eastern, #Religion & Spirituality, #History, #Middle East, #General, #Political Science, #Religion, #Islam

THE 1967 WAR

Nasser’s Yemeni misadventure presented him with yet another imperative to salvage his international prestige and his faltering leadership of the Arab cause. Far from unifying the Arabs, the civil war in Yemen had significantly heightened inter-Arab rivalries, with Saudi Arabia and Jordan on one side and Nasser’s UAR on another. The ruling Baʿthists in Damascus also remained mistrustful of Nasser and his designs on Syria. Moreover, while by this time Baʿthist officers had also taken over the reins of power in Baghdad, relations between Iraq and Syria remained cool and often tense. Elsewhere in North Africa, only revolutionary Algeria remained resolutely supportive of Nasser, having finally defeated the French in 1962 after a long, bloody war of liberation, and then having experienced a military coup of its own in 1965. Libya remained under the control of an archaic monarchy and, for now, was militarily and diplomatically marginal to the rest of the Middle East. Morocco had its own border conflict with Algeria, and Nasser’s support of the Algerian position did not endear him to the Moroccans. And Tunisia’s President Habib Bourguiba had repeatedly criticized

Nasser and other Arab “radicals” for their lack of realism and moderation.

23

By 1966, however, these divisions were temporarily masked because of heightened tensions between Israel and three of the frontline Arab states: Jordan, Syria, and the UAR. After Syria’s secession from the UAR in 1961, Palestinians were becoming increasingly suspicious of the commitments of the various Arab states to their cause; many feared that the state of Israel would become a permanent reality unless the entire political geography of the region was changed. The only way to bring about such a change, many reasoned, was to encourage the Arab countries to wage another war on Israel. Toward this end, to increase the potential for conflict, Palestinian commandos called the Fedayeen launched a low-intensity campaign of infiltrations and hit-and-run attacks against Israeli targets beginning in the early 1960s. In May 1964, the Arab League, and especially Egypt, had taken the lead in creating the PLO for the specific purpose of curtailing Fedayeen attacks on Israeli targets, thereby reducing the potential for war. These efforts were of little consequence, however. By 1966, because of Fedayeen raids as well as a number of other factors, Israel and its Arab neighbors were on a collision course, one that culminated in the Six Days’ War in June 1967.

The immediate causes of the 1967 War can be divided into three general categories: the highly volatile atmosphere of the region throughout 1966 and 1967, made all the more explosive by a series of bellicose statements coming out of Damascus and Cairo; the regional and international predicaments of Nasser; and the domestic political predicament of the Israeli prime minister at the time, Levi Eshkol. To begin with, there were the provocative activities of the Fedayeen. These commando raids had intensified after yet another coup in Syria in February 1966, when the new crop of ruling officers in Damascus were more sympathetic to the PLO’s main guerrilla unit, the Fatah. Adding to the tension between Israel and Syria were disputes over water resources and cultivation activities in their border areas, which had resulted in the massive aerial bombardment of Syrian villages by Israeli jets on several occasions.

24

Toward the end of 1966, the Soviet Union, which by now had started supplying a limited number of arms to Syria, announced that Israel was amassing troops along the Syrian border in preparation for an all-out invasion.

Nasser once again found himself in a quandary. As the self-proclaimed leader of the Arab world and the liberator of the Palestinians, the Egyptian leader could not remain on the sidelines for long. On November 4, 1966, the UAR and Syria signed a mutual defense pact, set up a joint military

command, and agreed to place their forces under the command of the Egyptian chief of staff in the event of war. Nasser hoped that this show of unity and force would deter Israel from further attacks on Arab targets.

25

But this was not to be, for shortly thereafter Israel mounted a serious attack on a Jordanian village, resulting in many casualties and the demolition of a mosque.

Throughout these months and into 1967, Nasser was keenly aware that the Arab armies were not prepared for war against Israel.

26

His strategy appears to have been one of trying to buy time until the Arab armies would be more united and stronger. “I am not in a position to go to war,” Nasser is quoted as having said around this time. “I tell you this frankly, and it is not shameful to say it publicly. To go to war without having the sufficient means would be to lead the country and the people to disaster.”

27

The bulk of his own forces were bogged down in Yemen, and those in Egypt had not had sufficient time yet to train and familiarize themselves with the advanced Soviet weaponry they were receiving. But Nasser had once again become a victim of his own rhetoric. When on April 7, 1967, the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) shot down six Syrian jet fighters over Syrian territory, Syria and Jordan both criticized Nasser for not having done anything in Syria’s defense. At this time the Egyptian president embarked on a campaign of intimidation against Israel, one over which he was soon to lose control.

Events now began unfolding far more rapidly than Nasser had anticipated. On May 15, amid maximum publicity, Egyptian troops started marching toward the country’s borders with Israel in the Sinai desert. Nasser also asked for the formal removal of the United Nations Emergency Forces (UNEF), which had been stationed along the Egyptian-Israeli border following the 1956 conflict. The UN secretary-general, U Thant, quickly agreed. Nasser then closed the Strait of Tiran, located at the southern tip of the Sinai, to Israeli shipping, an act Israel had vowed not to tolerate. Nasser’s fiery rhetoric continued unabated, however, and, in a dramatic gesture of unity, Jordan and the UAR announced the signing of a joint defense agreement and the placing of Jordanian troops under the command of an Egyptian general. Iraq and Saudi Arabia also announced their readiness to send troops in support of the Arab armies.

Throughout, Nasser had hoped to avoid a military confrontation with Israel and had at times moderated his rhetoric with proclamations to that effect. His primary goal was to score a political victory at Israel’s expense by forcing the Israelis to stop their massive retaliatory attacks on Jordan and Syria.

28

But the more he pursued this goal the more intractable and

inflexible his position became, to the point that he could not go back on his statements. Ironically, this was the same predicament in which the Israeli prime minister found himself in relation to other Israeli political actors. Levi Eshkol had often been accused of being weak and indecisive by the opposition Rafi Party and by members of his own Mapai Party.

29

Like Nasser, Eshkol was reluctant to wage war, fearing, among other things, that it might provoke retaliatory measures by the Soviet Union.

30

But once Egypt closed the Strait of Tiran, Eshkol had no option but to act. He brought in the popular retired general Moshe Dayan as the country’s new defense minister, and, in the early hours of June 4, the Israeli cabinet voted in favor of war. At 7:30

A.M.

on June 5, Israel commenced a relentless campaign of aerial assault against Egypt.

The Israeli campaign was brilliantly planned and executed. Because of Israel’s small size and population, its military doctrine had long been based on massive, surprise, offensive attacks that concentrated the greatest firepower on the biggest foe.

31

Accordingly, within the first few hours of the war, the Israeli air force managed to destroy almost all of the Egyptian airplanes that were parked in air bases within range of its jet fighters. These included seventeen airfields and approximately 300 aircraft.

32

By the end of the second day, the IDF claimed, it had destroyed a total of 418 aircraft from Arab countries, including 309 from Egypt, 60 from Syria, 29 from Jordan, 17 from Iraq, and 1 from Lebanon.

33

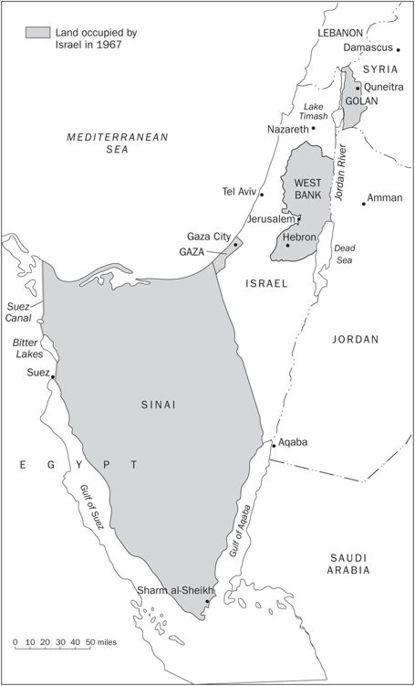

Left with no support from the air, Egyptian forces in the Gaza Strip were overwhelmed by the end of the second day, and by the end of the third day the entire Sinai, extending as far west as the Suez Canal, was in Israeli hands (map 5). Highways leading out of the peninsula were littered with bombed-out cars and buses carrying fleeing Egyptians.

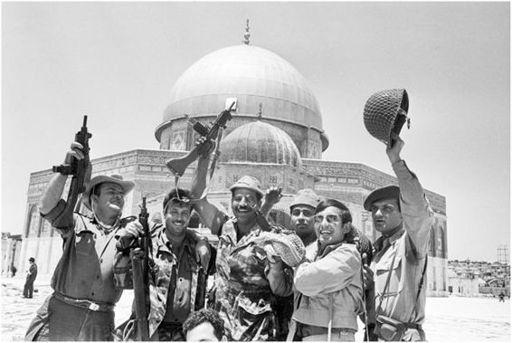

On the morning of the third day, June 7, Israeli forces turned their attention toward the Jordanian-controlled West Bank and, once again in complete control of the skies, overran Jordanian forces by that evening. The city of Jerusalem, with all its religious and historical significance for the Jews, was now in Israeli hands. For the first few days, the Syrian front had been relatively quiet, and activity there had been limited to isolated runs over Israeli territory by the remaining Syrian jets. On the fifth day of fight--ing, however, Israel initiated a massive attack on Syria, by the end of which it had captured the strategic Golan Heights. The Golan had housed Syria’s strategic missile batteries, whose positions had earlier been revealed to the IDF by an Israeli undercover spy named Elie Cohen.

34

The Syrians initial--ly put up a stiff resistance, but by early afternoon of the next day their defenses had collapsed and they retreated. Earlier, on June 7 and 8, Jordan

and Egypt, respectively, had agreed to a UN-sponsored cease-fire. Syria had also agreed to a cease-fire on June 9. Only after its capture of the Golan was complete, on June 11, would Israel agree to stop all hostilities.

Map 5.

Territories captured by Israel in 1967

Figure 9.

Israeli soldiers celebrating Jerusalem’s capture in the 1967 War. Corbis.

After six days of relentless attacks, Israel’s war against its Arab neighbors was over. In a brilliant series of military maneuvers and tactics, Israel had started, directed, and concluded a war all on its own terms. Within six days it had managed to wipe out the Arab air forces, rout the Arab armies, and capture the Sinai, the West Bank, and the Golan Heights. All in all, it was estimated that fewer than a thousand Israelis, both civilians and soldiers, lost their lives in the conflict. The casualties and losses on the Arab side were staggering: twenty thousand dead soldiers; twenty-six thousand square miles of lost territory; and thousands of prisoners of war, including, if the IDF is to be believed, nine generals, ten colonels, and three hundred other officers.

35

There were now also over 500,000 new Arab refugees (in addition to the Palestinian refugees from 1948), including 120,000 Syrians and 250,000 Egyptians.

36

The war had other profound consequences for the actors involved in it, both Arab and Israeli. For the Arabs, defeat, complete as it was, came to symbolize the fallacies of an entire era, of a style of politics and more generally a perspective incapable of coping with the realities of the surrounding world. A wave of recrimination and self-criticism was set in motion, and

the defeat brought on a deep psychological reevaluation of what Arab intellectuals saw as the chief culprits: incompetent leaders and their hollow regimes and, more importantly, the cultural milieu that had given rise to them. Even such sacred aspects of life as Islam and the Arabic language, with the latter’s penchant for hyperbole, were not spared from criticism.

37

A wave of Arab literary works appeared, including al-Sadiq al-Azm’s

Self-Criticism after the Defeat,

which has been called “one of the most impressive and controversial pieces of Arabic political writing in recent times.”

38

The revolutionary regimes of the day now came to be seen as “regimes of defeat” (

anzimat al-hazima

).

39

In the words of the noted Arab scholar Fouad Ajami, “What the defeat did was to show that the Arab revolution was neither socialist nor revolutionary: The Arab world had merely mimicked the noise of revolutionary change and adopted the outside trappings of socialism; deep down, under the skin, it had not changed.”

40