The Modern Middle East (18 page)

Read The Modern Middle East Online

Authors: Mehran Kamrava

Tags: #Politics & Social Sciences, #Politics & Government, #International & World Politics, #Middle Eastern, #Religion & Spirituality, #History, #Middle East, #General, #Political Science, #Religion, #Islam

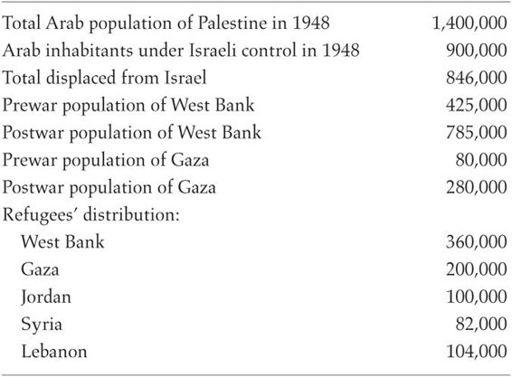

Table 3.

Palestinian Refugees of the 1948 War

SOURCE:

Samih K. Farsoun and Christina E. Zacharia,

Palestine and the Palestinians

(Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1997), p. 137.

Because of the geographic dispersion of the Palestinian nation and the birth of a Palestinian diaspora, its leaderless and organizationless character, and the larger geopolitical predicament in which it found itself, from 1948 until about 1967 Palestinian nationalism lost its geographic focus and gave way to a more encompassing, seemingly more powerful, Arab nationalism. This broader nationalism also came to be known as Pan-Arabism. That the primary rallying cry of Pan-Arabism was the liberation of Palestine is itself indicative of the resonance of Palestinian nationalism. But for a variety of reasons, many of which revolved around political considerations at home, the Palestinian cause was now picked up by non-Palestinian political aspirants near and far, large and small. Of these, by far the most influential and history making, and the one on whom not only the Palestinians but millions of other Arabs pinned their hopes, was Gamal Abdel Nasser. Nasser had been a volunteer from Egypt in the 1948 war and later became a lieutenant colonel in the Egyptian army. After 1952, he became Egypt’s

strongman. For nearly two decades, “Nasserism” would sweep across Egypt and the rest of the Middle East.

The 1948 war and the ease with which the Arab armies were defeated exposed the malaise of the Arab political order. In that war, an emergent, fundamentally European and colonial society struggling for its life and survival was pitted against an array of feudal monarchies with fragile domestic roots and little popular legitimacy. For the Arab side, the war was not so much a matter of life and death as a sideshow, an adventure, a chance to entertain illusions of grandeur and revive memories of old conquests. But, as it turned out, 1948 did become a matter of life and death for many of the Arab leaders involved, as their defeated armies, one after another, avenged their loss by turning against leaders seen as incompetent and corrupt, belonging to an era whose time had long passed.

Arab nationalism now assumed a new manifestation, articulated by young, restless Arabs yearning to emerge out of the shadows of their defeated leaders. This generation of Arabs was motivated not only by the shame of military defeat but also by a sense of solidarity with their Palestinian brethren, now scattered in refugee camps throughout the region. This post-1948 nationalism had three principal features. First, it was closely equated with “modernity,” seeking to rid itself of archaic, feudal traditions. Second, it was militaristic, seeing military might and discipline as immediate remedies for the defeat. Third, it saw strength in numbers, assuming that with unity the Arabs would become a force hard to defeat. Each of these strands was personified in Gamal Abdel Nasser, who from the mid-1950s until he was himself defeated by Israel in 1967 came to embody much of Arab nationalism.

At around the same time that Nasser was reaching the pinnacle of his popularity, a rich literature was beginning to emerge from various Arab nationalist intellectuals, some of the more notable of whom were the Egyptian Taha Hussein, the Yemeni Sati al-Husri, and the Syrian Michel Aflaq.

65

Nasser’s nationalism, of course, was practical and political, not literary or intellectual. He was a soldier, a politician, a political animal in every sense of the word. His astounding appeal among the masses—his success in presenting himself to the peoples of Egypt and other Arab states as their hope and their savior—came from tapping into nationalist forces that had long been dormant and were desperate to be released. Increasingly, for a time at least, the question of Palestine, the catalyst for the emergence

of this latest phase of Arab nationalism, was pushed into the background. It became fodder for the rhetoric of nationalism, but the actual focus and substance of that nationalism was Egypt and its president, Nasser.

Gamal Abdel Nasser was born in Alexandria on January 15, 1918. His generation came of age at a time of profound political instability, corresponding with historic developments occurring not only in Palestine but also much closer to home, in Egypt itself. The Egyptian monarchy, under the incompetent and corrupt leadership of King Farouq, presided over a country that was only nominally independent, with Britain maintaining a heavy-handed presence in Egypt’s economic and political life. Political chaos was the order of the day, with various groups often agitating against the monarch, the British, or, more commonly, both. Perhaps the most important was the Wafd Party, formed after World War I by a group of wealthy Egyptian landowners and industrialists. The Wafd emerged as an especially important player in Egyptian politics in the final years of the monarchy, but after 1952 it withered away and did not reemerge until the late 1970s. Even more instrumental in the collapse of the monarchy was the Muslim Brotherhood (Ikhwan Muslimeen), established in 1928, an ardent advocate of the need for greater social morality and full independence from Britain. Beginning in 1933, a group calling itself the Young Egypt Society (Misr al-Fatat) was also formed. Made up mostly of students at Cairo University’s Law Faculty and seeking to imitate the example of European fascists, the society’s adherents called themselves the Greenshirts and often clashed with Wafdist Blueshirts. Organizations such as the Muslim Brotherhood and the Young Egypt Society were essentially nationalist and populist, and although they seldom had a coherent platform or ideology of their own they were united in disliking the ruling elite, deploring its military and political incompetence, and wishing to reverse the general malaise that gripped Egyptian and the larger Arab social and political life. By the mid-1930s, both groups had penetrated the Egyptian army and were beginning to attract followers among the officer corps.

66

More importantly, their efforts had helped create a political atmosphere highly charged against both the monarchy and the British. It was in this context that Nasser entered the Military Academy in 1937 and, from there, rose relatively quickly through the ranks of the army. By 1952, he had become a lieutenant colonel.

67

It did not take long for Nasser to become politically active. The early to mid-1940s were especially traumatic for Egyptians and for the larger Arab world in general, culminating in the 1948 war. In 1942, for example, the British had humiliated King Farouq by surrounding his palace with tanks and ordering him to appoint as prime minister a politician of their

choosing. Soon after returning from the Palestine war, in late 1949 Nasser organized a secret military cell, called the Free Officers, with the specific aim of capturing political power. Nasser’s own words are revealing: “We were fighting in Palestine but our dreams were in Egypt. Our bullets were aimed at the enemy lurking in the trenches in front of us, but our hearts were hovering around our distant Mother Country, which was then prey to the wolves that ravaged it.”

68

The group, which by the early 1950s numbered into the hundreds, was made up mostly of younger, junior officers, many drawn from the Military Academy itself, where Nasser had become an instructor. Although void of a “philosophy” per se, the cabal was united around certain key principles: getting rid of the king and his clique, putting an end to British imperialism, and using the armed forces to achieve national objectives. The years 1950 through 1952 were especially tense, characterized by frequent assassinations of political figures and sporadic violence. Finally, in the early morning hours of July 23, 1952, the Free Officers staged a relatively bloodless and swift takeover of the state. The government was overthrown and replaced by a Revolutionary Command Council (RCC), made up of the nucleus of the Free Officers movement. Within days, King Farouq was forced to abdicate. A new order was proclaimed; the revolution had begun.

Too young to be assured of their own credibility before the Egyptian people, in September members of the RCC asked an older, popular army general, Muhammad Naguib, to serve as the prime minister. The following January all political parties were outlawed and a three-year “transition period” was declared, during which the RCC was to rule and to facilitate the country’s revolution. Nasser wrote that year (1953) that “political revolution demands, for its success, the unity of all national elements, their fusion and mutual support, as well as self-denial for the sake of the country as a whole.”

69

In June Egypt was proclaimed a republic and Naguib became its first president, still retaining the office of the prime minister. But the president’s star did not shine for long, and he soon fell victim to Nasser’s machinations in the RCC. In February 1954, the RCC branded Naguib a traitor and ousted him. A month earlier, the RCC had banned the Muslim Brotherhood and had suppressed pro-Naguib elements within the army and among street demonstrators. Naguib was brought back temporarily, now only as president and with much-reduced powers, but within a few months he was accused of complicity in a plot to assassinate Nasser and was removed from office again, this time for good. By 1956, Nasser had clearly emerged as the dominant figure within the RCC, having a year earlier represented Egypt at the NonAligned Summit

in Bandung, Indonesia, where he had been hailed as the leader of Egypt and the Arab world. In a referendum held in June 1956, a new constitution was inaugurated, based on which the RCC was formally abolished and Nasser was elected to the presidency. Within months, the president was to reach the pinnacle of his power and popularity because of the Suez Canal crisis.

Before discussing the Suez Canal crisis and its consequences, a word needs to be said about Nasser’s march from relative obscurity in the late 1940s to the height of power by the mid-1950s. In

The Philosophy of the Revolution,

which he wrote in 1953 and published the following year, Nasser admitted that the transformation of his military coup to a full-blown revolution was a matter more of necessity than of advanced planning. “After July 23rd I was shocked by the reality. The vanguard had performed its task,” he wrote, referring to the military. “It stormed the walls of the fort of tyranny; it forced Farouk to abdicate and stood by expecting the mass formations to arrive at their ultimate object. . . . A dismal picture, horrible and threatening, then presented itself. I felt my heart charged with sorrow and dripping with bitterness. The mission of the vanguard had not ended. In fact it was just beginning at that very hour. We needed discipline but found chaos behind our lines. We needed unity but found dissensions. We needed action but found nothing but surrender and idleness.”

70

For all his efforts behind the scenes, first among the Free Officers and then within the RCC, initially Nasser was neither generally liked by the Egyptians nor trusted very much. In fact, many feared him, and, as the brutal crackdown on the Muslim Brotherhood and other dissidents showed, they did so for good reason.

71

But once the popular Naguib was out of the picture, it was Nasser’s turn to shine, and this he did by two primary means: his foreign policy, and his populist domestic social and political programs.

In domestic politics, Nasser knew the language of the street, having himself risen from a modest middle-class background. His rhetoric was electrifying, his charismatic personality magnetic, his message simple and compelling. Following an alleged attempt on his life by members of the Muslim Brotherhood in Alexandria on October 26, 1954, Nasser, unscathed, climbed to the podium and delivered a rousing speech: “My countrymen, my blood spills for you and for Egypt. I will live for your sake, die for the sake of your freedom and honor. Let them kill me; it does not concern me so long as I have instilled pride, honor, and freedom in you. If Gamal Abdel Nasser should die, each of you shall be Gamal Abdel Nasser.”

72

This was a far cry from the image the average Egyptian had

come to have of King Farouq or, especially, British officials. Nasser’s charisma was backed by a series of highly popular social policies, chief among which was the Agrarian Reform Law, enacted by the RCC in September 1952 within weeks of his coming to power.

73

Another project in which Nasser

was personally involved from the earliest days, the construction of the High Aswan Dam, was also a matter of national pride and a highly emotional issue for all Egyptians. To present a forum for the participation of the masses, in 1953 a Liberation Rally organization was formed, with Nasser as its secretary-general. All other parties were banned shortly thereafter. In 1956 a new constitution was promulgated, and the Liberation Rally changed to a new party, the National Union (NU). In 1962, when under the aegis of a Socialist Charter the regime formally adopted socialism as the most desirable path for social transformation, the NU was changed to the Arab Socialist Union (ASU).