The Making Of The British Army (30 page)

Read The Making Of The British Army Online

Authors: Allan Mallinson

By the end of the war the army had become as efficient as any on the Continent, in its own very British way. The French colonel Thomas Bugeaud, who would win laurels as a marshal of France in Algeria in the 1830s, had been a regimental commander in Spain, and observed simply, ‘The British infantry is the most dangerous in Europe. Fortunately it is not numerous.’ As for Wellington, who later in life admitted to one fault in command – ‘I should have given more praise’ – he said of his Peninsular army simply, ‘I could have taken it anywhere and done anything with it.’

And the army’s success was of his making – his personal making. Sir Arthur Wellesley, in turn viscount, marquess and finally duke of

Wellington, had not had a day’s leave since landing in Portugal in 1809, and his daily rate of work – at his desk or in the saddle – had been prodigious. It was necessary, he said, that a general be able to trace a biscuit from Lisbon all the way to the army in the field. This was the way that war was made, and he had learned how to do it in India. Marlborough had learned it through a longer process of experience in Flanders, and through a practical intuition, a doctrine of common sense which Wellington shared. Both commanders, in their own fashion, had evolved a way of making war that perfectly suited the nation’s character and the realities of its politics and economy.

The army’s foundations had been laid out, if erratically, in the Civil War and at the Restoration; they had then been dug deep and well in Marlborough’s time; and the walls had been securely raised in the Peninsula. There was much building work still to do, and there would be earthquakes, fire and flood that would shake the edifice to its foundations. Neglect would bring dilapidation, so that the roof would fall in from time to time; but the structure would remain fundamentally sound, and no assault on it would bring about complete collapse. No army of any sovereign nation in 1814, except that of the United States, would be able to look back a century and a half later and make that claim.

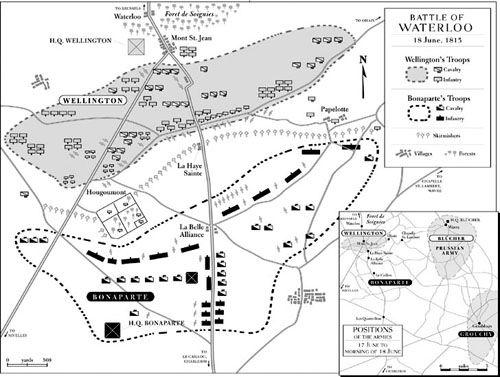

Waterloo, 1815

AND SO CAME THE ARMY’S (AND WELLINGTON’S) GREATEST TEST: THE BATTLE

that defined the rest of the nineteenth century and whose name is deeply etched in the minds of soldiers today, even if they know little of its details. ‘Waterloo’ stands for something timeless and fundamentally unshakable in the way the British army conducts itself in defence: endurance to the end by the man with the rifle; self-sacrificing offensive action by the cavalry; limpet devotion by the artillery to its guns; officers standing side by side with their men; the triumph of simple duty; fortitude in the face of seemingly overwhelming odds – and, of course, some brilliance. That the battle was, in Wellington’s words next day, ‘a damned nice thing – the nearest run thing you ever saw in your life’ makes it all the more powerful an exemplar. Victor Hugo, ever anxious to rewrite any fact of Waterloo to explain that it was either in truth a French victory or at worst a

diabolical

defeat, calls it in

Les Misérables

‘a battle of the first rank won by a captain of the second’. But he makes this extraordinary claim ostensibly to make a much greater point: ‘What is truly admirable in the battle of Waterloo is England, English firmness, English resolution, English blood. The superb thing which England had there – may it not displease her – is herself; it is not her captain, it is her army.’

Hugo has never found himself in strong company with that view of

Wellington. Nevertheless the victory was the army’s too, certainly; and the manner of victory did indeed show what the army had become. For however vaunted the opponent, however inadequate the British appeared by comparison, there was some ingredient in Wellington’s army, some sort of leaven, that could make it rise to any occasion. Wellington himself likened his way of campaigning to the practical business of horse furniture: ‘The French plans are like a splendid leather harness which is perfect when it works, but if it breaks it cannot be mended. I make my harness of ropes, it is never as good looking as the French, but if it breaks I can tie a knot and carry on.’ And this make-do-and-mend approach seemed to reach right down to the ranks of red: no matter what the setback, every man would simply ‘tie a knot’ and move on. In 1914 the Kaiser is supposed to have referred to Britain’s ‘contemptible little’ army (see ‘Notes and Further Reading’); the soldiers of that army immediately started calling themselves ‘the Old Contemptibles’ and proceeded to deal with the myth of Prussian military invincibility with contempt. A recurring feature of history has been the enemy’s underrating of the British army, failing to see beyond its sometimes ramshackle appearance to what lies deeper. An army that could tie knots, and use them as it did at Waterloo, could be expected to do so again.

The 1815 campaign was an affair of a few days only before its climax at Waterloo. Forced to abdicate the previous year as the armies of Britain, Austria, Prussia and Russia began closing on Paris and consigned to exile on the island of Elba, Napoleon escaped at the end of February and arrived in his old capital on 20 March – the costliest flight from exile until Lenin slipped out of Switzerland a hundred years later. Louis XVIII, whom the allies had restored to the French throne, was already an unpopular king and soon fled to Belgium, now united with the Dutch crown. Napoleon at once began resurrecting the Grande Armée, while the allies at the Congress of Vienna agreed to do what they had done the year before and close in on Paris, although this time the British would be approaching from the north rather than from over the Pyrenees. An Anglo-Dutch army would assemble in Belgium, based on a nucleus of British troops already in the Low Countries, where they would be joined by 100,000 Prussians. A huge Austrian army of 200,000 would enter France through Alsace-Lorraine, followed by the Russians in roughly the same strength later in the summer.

Napoleon could not hope to counter these numbers if they combined. He therefore decided on an immediate offensive against the Anglo-Dutch and Prussian forces: if he could destroy, or even just defeat them it might deter the Austrians and Russians from risking a similar fate. And it would buy him time to raise more troops and to put the eastern fortresses on to a strong footing.

Immediately, the duke of Wellington took command of the Anglo-Dutch army and began staff talks with the Prussians under their doughty old commander Prince Gephard von Blücher. Wellington and Blücher saw eye to eye over the need for a defensive strategy, although Blücher’s chief of staff, Gneisenau, distrusted the duke: British armies in Flanders had run for the sea often enough. The allies were, in fact, too weak to risk an offensive, especially since the reliability of the Dutch – Belgian element was questionable and half the British regiments were inexperienced.

75

Besides, a defensive strategy best suited Wellington’s instincts; certainly it played to the British army’s strengths.

In turn, Napoleon knew he was not strong enough to fight both Wellington and Blücher in the same battle. He would therefore have to deal with them one before the other, making sure they could not combine. This – dealing with two armies – he had done often enough before. Success consisted in hitting one of them so hard that it had to withdraw to recover, turning to the other army and destroying it utterly, and then if necessary returning to the first to destroy it in detail. The trick was never allowing one of them to render support to the other.

Wellington and Blücher understood this perfectly, and were resolved to remain in close mutual support. The flaw in allied cooperation lay, however, in their respective lines of communications: if they gave way in the face of a huge French offensive the two armies would naturally begin to diverge, for the British supply lines ran north-west to the Belgian ports, while the Prussians’ ran east to the Rhineland. And it was this fault-line, the boundary between the two armies, that Napoleon intended exploiting.

Wellington had another factor with which to grapple in his calculations: the French axis of advance on Brussels (their presumed

objective) might be from the south through Charleroi, or from the south-west through Mons or even Tournai. An offensive from the south-west would threaten his lines of communication, and he would have to dispose a considerable force to guard them. He could not deploy the army forward on the border until he knew Napoleon’s real axis of advance, for there would not be time to switch positions. And besides, the problems of billeting and supply, particularly fodder for the cavalry and artillery, obliged him to have his troops more dispersed than he would have liked. But he was confident that he would have good and early intelligence of French moves: he had his trusted spies and observing officers in Paris and elsewhere. If he had had greater confidence in his cavalry he might have arranged some reconnaissance with the Prussians across the French border: it would at least have spared him tactical surprise when Napoleon appeared with all his men – to the complete amazement of both him and Blücher – before Charleroi on 15 June. Wellington was not exaggerating when he exclaimed, ‘Napoleon has humbugged me, by God!’

On the sixteenth the French inflicted a sharp reverse on the unsupported Prussians at Ligny, Blücher himself being unhorsed and almost killed. Racing south from Brussels, gathering up the army as he went, Wellington managed to fight an action on the extreme right (west) of the battle area at Quatre Bras. Had Marshal Ney –

le brave des braves

, as Napoleon had dubbed him – whose job it was to deal with any appearance of the Anglo-Dutch, pressed his attack with more vigour, Wellington might have been forced from the ground. By nightfall, however, he was still in possession of the crossroads which gives its name to the village and the battle. There is probably some truth in the idea that Ney did not press the attacks because he knew Wellington’s trick of keeping the main part of his force concealed, and that he was wary of being wrong-footed (he had seen the British army at Bussaco and Torres Vedras). Such is the ‘virtuous circle’ of good tactics.

Whatever the reason, however, Ney’s apparent timidity allowed some semblance of cooperation between the allies at a crucial moment. Despite Gneisenau’s urging that the Prussians withdraw east, in the belief that Wellington had failed to show sufficient resolve in supporting them, Blücher promised to fall back north instead, and to continue the fight. For his part, Wellington would withdraw to the ridge of Mont St Jean before the village of Waterloo on the southern edge of the Forest of Soignes and astride the Charleroi – Brussels high road, and there give

battle when Napoleon switched his main effort – as both he and Blücher knew he must.

Next day, the seventeenth, in heavy rain, the Prussians began to withdraw as agreed. Emmanuel de Grouchy – who had commanded Napoleon’s escort on the retreat from Moscow, but who had only now been made a marshal – at once advanced to harry them, and by one of those misreadings of the situation usually ascribed to ‘the fog of war’ sent back a report to Napoleon that Blücher was withdrawing east. He had, in fact, mistaken the supply train for elements of the army itself. Thus confirmed in his own good opinion of his strategic skill, Napoleon turned with a vengeance on the Anglo-Dutch, believing the Prussians to have been knocked out of the contest. Wellington’s withdrawal to Mont St Jean went well, however: just as Lord Paget and his cavalry had covered Sir John Moore’s escape from east of the Esla River, allowing the infantry to gain a head start for Corunna, so now would the Marquess of Uxbridge – as Paget had become – cover the infantry back from Quatre Bras.

76

The wet and weary regiments of foot which tramped to their watery bivouacs on the ridge that night, joining those whom Wellington had ordered up directly, had much to thank Uxbridge’s cavalry for, though they had not actually seen anything of them – appreciating only the absence of French

cuirassiers

harassing them on the march back.