The Making Of The British Army (33 page)

Read The Making Of The British Army Online

Authors: Allan Mallinson

The Crimea, 1854–6

OF THE THREE STIRRING ACTIONS ON 25 OCTOBER 1854 IN THE CRIMEA, THE

last, the charge of the Light Brigade, is undoubtedly the best known. Five regiments of light dragoons, hussars and lancers, all considerably under strength due to the privations of the climate and the campaign – around 650 men in all – galloped behind Major-General the Lord Cardigan down a valley lined with Russian guns and riflemen to attack an artillery battery which threatened no one. As an example of incompetence and futility it is not unique, but it is perhaps the most picturesque, and certainly the most poetically lauded. ‘C’est magnifique, mais ce n’est pas la guerre,’ was the French Marshal Bosquet’s memorable opinion. But earlier that morning there had been a sharp little action in which the double rank of bayonets of the 93rd (Sutherland) Highlanders – ‘a thin red streak tipped with a line of steel’ in the words of William Howard Russell,

The Times

’

s

war correspondent – had stopped the advance of the Russian cavalry towards the port of Balaklava, the army’s supply base. Their brigade commander, Sir Colin Campbell, had called out from atop his horse, ‘There’s no retreat from here, men. You must die where you stand!’ – to which possibly the most printable reply was ‘Aye, Sir Colin. If needs be, we’ll do that.’

Campbell, who had celebrated his sixty-second birthday only three days before, had earned his spurs in the Peninsula (he had been with

Moore at Corunna – indeed, he had been at Moore’s old school, Glasgow High – and then with Wellington throughout Spain), and had seen much action since then in various corners of the expanding Empire, including China and India. And on the morning of the twentyfifth his long, broad and recent experience was translated into good judgement, for he had formed a low opinion of the Russian cavalry during the operations since the army had landed in the Crimea a month before. When, therefore, the alarm had gone up that enemy cavalry was advancing on Balaklava, and he stood-to the 93rd on outpost duty, he decided to risk sacrificing depth, and even the security of the square, in order to form a longer line and thereby gain greater firepower, drawing them up two deep rather than in the four ranks conventional in the face of cavalry.

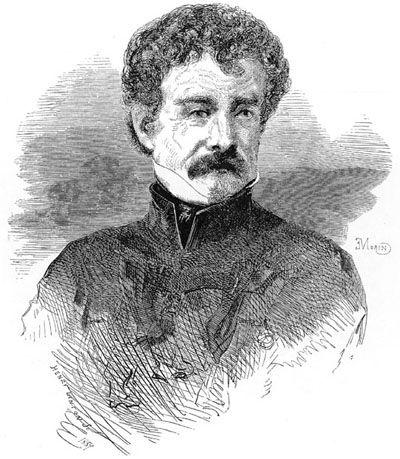

Lieutenant-General Sir Colin Campbell (later Field Marshal Lord Clyde) – one of the best commanders-in-chief the army never had.

The 93rd were one of the battalions fortunate enough to have the new Minié rifle (others still carried the Brown Bess musket that their forebears had used at Waterloo), which could be loaded quickly and was accurate enough for volley fire at half a mile.

83

Supported by some Turkish infantry and Royal Marines, they fired their first volley at 800 yards, a second at 500, and then again at 350 yards. As the Cossacks and hussars closed for the charge, their ranks thinned but still intact, their commander suddenly pulled up sharp, convinced that the ‘thin red line’ of riflemen was a decoy backed by a much stronger force waiting to counter-attack. He turned them about and began withdrawing at the walk.

Some of the Highlanders started forward for a counter-charge. ‘Ninety-third, damn all that eagerness!’ cried Campbell, halting them with the flat of his sword. But the eagerness was evidence enough that 100 years after Minden – and with forty years of peace in Europe – going to it with the bayonet, even against mounted men, was still the instinct of the British infantryman.

Next came evidence that the same offensive spirit that had propelled Lord Uxbridge and the Union and Household brigades into the great mass of d’Erlon’s columns at Waterloo was no less alive. It was not, however, Cardigan’s famous charge with the Light Brigade, but the

equally astonishing and far more effective, if much lesser known, charge of the Heavy Brigade – three regiments of dragoons and dragoon guards, bigger men on bigger horses, under Brigadier-General James Yorke Scarlett. Watching it from his place at the head of his regiment was Lord Uxbridge’s sixth son, Lord George Paget, deputy commander of the Light Brigade. A day or so later, after his own foray ‘into the valley of death’, he wrote of the Heavies:

This noble brigade was on its way to cross the Balaclava plain from our rear (where it had been formed up in our support), with the object of giving support to the 93rd Highlanders, whose position was seriously threatened. It had just reached the level of the plain beneath us, when large masses of the enemy’s cavalry appeared, rapidly advancing, and debouching, as it were, from the plain which was afterwards the scene of our charge, having crossed the ridge of redoubt hills at a point where the undulation of the ground leaves little rise from the plain itself…

This advancing column could not have been 300 yards from the Heavy Brigade when they first came upon their view. These last were at that moment in the act of executing their flank movement, and close on their left (between them and the enemy) were the remains of a vineyard.

Anyone who has ridden, or attempted to ride, over an old vineyard will appreciate the difficulties of moving among its tangled roots and briars, and its swampy holes. But these did not stop these noble fellows. They were caught in a position and formation quite unprepared for what was to follow, aggravated as this was by the nature of the ground. They immediately and most skilfully showed a front to their left, and advanced across the vineyard to meet a foe of many times their number.

It must be here observed that the confines of this vineyard were just on the line where the shock took place between the two advancing bodies; or rather that the Heavy Brigade had only just time to scramble over the dry ditch that usually encircles the vineyards, when they came in contact with their foes.

I am now about to describe only what I saw! — This has been called a charge! How inapt the word! The Russian cavalry certainly came at a smart pace up to the edge of the vineyard, but the pace of the Heavy Brigade never could have exceeded eight miles an hour during their short advance across the vineyard. They had the appearance (to me) of just scrambling over and picking their way through the broken ground of the vineyard. Their direct advance across the vineyard could not have exceeded eighty or one hundred yards. What a thrilling five-minutes (for it did not last longer) was the next — to us spectators!

The dense masses of Russian cavalry, animated and encouraged doubtless by the successes of the morning (for the poor slaves had been told that the Turkish redoubts had been taken from the English) — advancing at a rapid pace over ground the most favourable, and appearing as if they must annihilate and swallow up all before them; on the other hand, the handful of red coats [the heavy cavalry wore red] floundering in the vineyard, on their way to meet them.

Suddenly within twenty yards of the dry ditch, the Russians halt, look about, and appear bewildered, as if they were at a loss to know what next to do! the impression of which appearance of bewilderment is forcibly engraven in my mind on this occasion, as well as later in the day. They stop! The Heavies struggle — flounder over the ditch and trot into them!

Then followed anxious moments! ‘red spirits and grey,’ green coats and blue! all intermingled in one confused mass!

The clatter of the swords against the helmets, the trampling of the horses, the shouts! — in short, the din of battle (how expressive the term) still rings in one’s ears! One body must give way. The heaving mass must be borne one way or the other. Alas, one has but faint hopes! for how can such a handful resist, much less make head through, such a legion? Their huge flanks lap round that handful, and almost hide them from our view. They are surrounded and must be annihilated! One can hardly breathe! Our second line (half a handful) makes a dash at them! One pants for breath! — one general shout bursts from us all! It is over! They give way! the heaving mass rolls to the left! They fly! Never shall I forget that moment!

There is no more show of resistance, and they soon disappear to whence they came. It was a mighty affair, and considering the difficulties under which the Heavy Brigade laboured, and the disparity of numbers, a feat of arms which, if it ever had its equal, was certainly never surpassed in the annals of cavalry warfare, and the importance of which in its results can never be known.

84

The success of the Heavies was all the more surprising because – like Cardigan, and even the divisional commander Lord Lucan – Scarlett had no experience of active service whatever.

85

He had been commissioned into the 18th Hussars three years after Waterloo and had

risen by purchase to the rank of lieutenant-colonel in the 5th Dragoon Guards. He had then held this command for an astonishing fourteen years until on the outbreak of the Crimean War he was appointed commander of the newly formed Heavy Brigade. To have decided on an immediate attack against such a vastly superior number of cavalry – his brigade could muster only 300 sabres that morning – and against the advice of his two regimental commanders was the stuff of a Colin Campbell. Whence came his brilliant

coup d’œil

?

It was ultimately Scarlett’s decision, and certainly his responsibility, but it was his two aides-de-camp, both of whom had seen service in India, who urged the attack. Faced with the same overwhelming numbers of Marathas, Pindarees or Sikhs, the trick had always been to charge at once, before the enemy decided to, gaining the moral ascendancy and also the advantage of speed (it was, after all, what had saved the young Arthur Wellesley at Assaye). ‘India’ had stopped the Cossacks in their tracks in front of the 93rd Highlanders, and it was ‘India’ again that overthrew the Russian hussars and lancers opposing the Heavy Brigade. Why, therefore, did ‘India’ not come to the rescue of the Light Brigade during the confusion leading to the attack on the Russian guns? Why, indeed, did it seem to speed it to its destruction?

The reason why – the title of Cecil Woodham Smith’s unsurpassed account of the débâcle – is to be found in the aftermath of Waterloo. As was to be expected, there had been wholesale cuts in the army establishment (and in the navy, where almost every three-decker was decommissioned), for the usual reasons of economy and fear of militarism. But the army that remained was much the largest the country had ever supported in peacetime. Law and order at home remained the army’s business, and with political, agricultural and industrial unrest rife in post-war England, the spectre of revolution was enough to frighten the authorities into keeping more cavalry regiments in being than initially intended. Even so, by 1820 the army’s establishment had been reduced to 100,000, less than a quarter of its pre-Waterloo strength. Not only was it smaller, its distribution was also very different from what it had been before ‘the never-ending war’. Only half the troops were in the United Kingdom, and a large proportion of these were in Ireland; there were 20,000 in India (besides the army of the East India Company) and 30,000 scattered about the world piecemeal in colonies and bases, many acquired during the war. These included 5,000 in Canada, where the bruising War of 1812 with the United States

had left scars and an unresolved frontier prompting vast expenditure on military canals and fortifications. But as peace took root in Europe – international peace, for there was civil war enough – the economies increased. When the duke of York died in 1827, still in harness as commander-in-chief, his funeral arrangements were delayed by the difficulties of arranging decent ceremonial. Britain, said many a senior officer in despair, did not have enough troops to bury a field marshal.

86