The Making Of The British Army (72 page)

Read The Making Of The British Army Online

Authors: Allan Mallinson

One of the reasons for this distinctiveness was the annual training

regime. After 1945, training had taken place over German land almost as if the war had not ended, and after 1955 this military ‘right to roam’ continued, except that compensation was paid for damage. And since the north German plain was largely under crops, large-scale armoured manœuvres could take place after the harvest with relatively little damage. Apart from the Libyan desert (which, after Captain Gaddafi’s coup in 1969, was no longer available for training) or the Canadian prairie (with its huge logistical demands), it was the only place where British armoured troops could range freely and realistically – with the added advantage of its being the very terrain on which they expected to fight. Brigade, divisional and even corps commanders and their staffs were able to practise their art with the essential element of Clausewitzian ‘friction’ included – something which paid off handsomely in the First Gulf War. As, too, did three decades of increasingly sophisticated equipment procurement stemming from BAOR’s highly focused operational requirements – producing, notably, the Challenger tank and the Warrior infantry fighting vehicle, which though conceived on the north German plain at the height of the Cold War have twice battled with Iraqi forces in the desert.

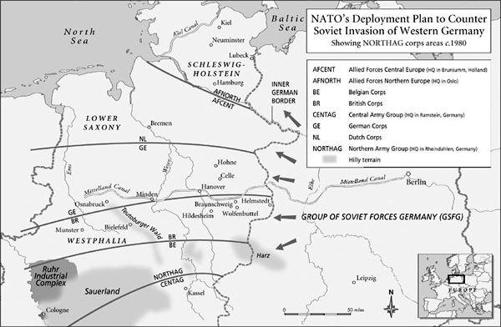

Every year for the best part of four decades before the First Gulf War there were months of preliminary ‘special to arm’ training – firing practice for every rifle and machine gun, every tank, every artillery piece; mine-laying and bridging for the sappers, signals exercises for the headquarters and the like – preceding the annual autumn manœuvres, and always in an atmosphere of intense competition, rivalry and scrutiny. There never was a British army so primed for its task and at such a permanent peak of efficiency: the proximity of the enemy, in hailing distance across the IGB like some silent reincarnation of the Western Front, made it all both real and immediate. Indeed, the Russians monitored all radio traffic and spied on all exercises; and the troops in BAOR relished the thought of it. There were detailed deployment plans which were constantly studied, refined and rehearsed, and strict controls on manning to keep 1st (British) Corps at high readiness (no more than 10 per cent of a regiment’s strength could be out of the country). Ninety per cent of armoured vehicles had to be available to move at four hours’ notice, placing a constant and heavy strain on the repair and logistic chain. In the ‘readiness war’, the REME, RAOC and RCT were the principal warriors.

260

And in case the threat from across

the IGB did not always seem imminent enough, there were NATO teams ready to swoop on a regiment in the middle of the night to test every detail of its fitness for the fight – from the calling in of married soldiers to the out-loading of ammunition. ‘Satisfactory’ and the commanding officer lived to prove himself another day; ‘Unsatisfactory’ and his promising career would be at an end.

All of this made for a remarkable cohesiveness: senior commanders knew their junior officers; soldiers knew their generals;

everybody

seemed to know everybody else (it was said that cavalry officers only married the sisters of other cavalry officers, since they were the only girls intrepid enough to leave London for a regimental dance on Lüneburg Heath in midwinter). Every weekend there were hunter trials, polo matches, sailing regattas – contests in every conceivable activity, which all added to the atmosphere of energy and competition. The army had learned how to live abroad in India and the Middle East, and it applied that experience in full measure to Germany, the only difference being that the natives were marriageable.

There was a negative side, however: a tendency to think in terms of set moves to defeat a specific part of the Soviet war machine on a particular piece of ground in a precise phase of a well thought-out plan. It was Montgomery’s ‘everything went to plan’ taken to extremes that would in fact have dismayed him. The lessons of the Second World War in handling armour – boldly and flexibly – were also progressively abandoned because of the political requirement to hold ground as close to the IGB as possible, which resulted in a concept of positional defence not dissimilar to that of France in 1940. This state of affairs was rectified to an extent in 1984 when General Sir Nigel Bagnall became Commander Northern Army Group and persuaded the Germans to stop thinking about defending every inch of ground and embrace their tank warfare heritage instead. This in turn eased the general tactical constipation which was besetting the British army, and when Bagnall (who as an infantryman before transferring to the armoured corps had won an MC and bar – a second MC – in Malaya) became CGS the following year,

261

he began a root-and-branch reform of the army’s tactical doctrine – indeed, of the whole art of campaign planning. Bagnall had studied deeply the German experience on both eastern and western fronts in the Second World War, as well as Israeli tactics in the

Six Day War of 1967 and the 1973 Yom Kippur War, and also contemporary American thinking about ‘deep manœuvre’. By the end of the 1980s, in large measure as a result of Bagnall’s single-mindedness, the British army had become a freer-thinking organization than it had been for decades, and the arrival into service of world-class equipment such as Challenger and Warrior – and, later, the Apache attack helicopter – gave wings to the new spirit of ‘mission command’ (what the Germans themselves had long called

Auftragstaktik)

in which a subordinate is given far greater operational latitude than in the previous regime of

Befehlstaktik

(‘order command’), in which the commander supervises everything himself and imposes his view not only of what must be done but exactly how.

The fall of the Berlin Wall, and soon of the Soviet Union itself, came as a victory for the Cold Warriors of BAOR, but it was at the same time their

congé

, for the new Conservative government of John Major was determined to scavenge a hefty ‘peace dividend’ from the rubble. And so, as in the past after victory in war, the nation sought to reduce its army. But before the cuts could be made there would be a sort of curtain call for the victorious BAOR: Saddam Hussein, Iraq’s pseudo-military dictator, had invaded Kuwait in August 1990, and the UN Security Council had authorized a US-led coalition to eject him.

Over the course of several months 1st Armoured Division, consisting of two armoured brigades (including the 7th, the famed ‘Desert Rats’ of 8th Army) and one of artillery, moved by rail, sea and air from Germany to the Saudi desert to form the second largest of the coalition’s components – with all its supporting elements, some 43,000 men (and women), and two and a half thousand armoured vehicles. The operation was named Granby after the hero of Warburg, the celebrated bald-headed commander of British troops in Germany in the Seven Years War.

After months of training, and a punishing air campaign against the entire Iraqi command and control system and its obsolescent army dug in in the desert, on 24 February 1991 US General Norman Schwarzkopf’s force thrust across the Saudi – Iraq border just to the west of Kuwait (with US Marines and Saudis making straight for Kuwait City itself). After penetrating deep into Iraqi territory they turned east to attack the Republican Guard – the best of Saddam’s

formations – in the flank, with 1st Armoured Division protecting the right of this great turning movement.

The effect was dramatic: outgunned, outfought and totally outmanœuvred, within forty-eight hours Iraqi troops were retreating from Kuwait. Schwarzkopf’s forces pursued them to within 150 miles of Baghdad before being ordered to withdraw – perhaps one of the greatest lost opportunities of recent times (if, that is, the coalition could have got UN sanction to remove Saddam). One hundred hours after the ground campaign started, President George Bush declared a ceasefire. Iraqi casualties had been heavy; those of the coalition quite remarkably light.

Among the many lessons of the First Gulf War – in command and control, logistics, ‘friendly fire’ and the hundred and one other areas in which professional soldiers look to learn after any war – there was one ‘geopolitical’ truth that would have the profoundest effect on the shape of things to come: the only army in the world capable of operating with, as opposed to merely alongside, the US army in high-intensity war was the British. The French, who had withdrawn from the military structure of NATO decades before, were hopelessly ‘national’ in their equipment and doctrine, with little interoperability. The Germans were constitutionally – in both senses – unable to break loose from the

Heimat

, for the Hitler and then the Soviet years weighed as heavily on them as the Somme once had on the shoulders of British generals. And no other NATO ally possessed either the hardware or the confidence. Since the First Gulf War, the British army has thought of itself increasingly (without admitting it quite) as the US army’s auxiliary, and its determination to maintain a capability for high-intensity operations of the Gulf War type has driven its restructuring and equipment programmes up to the present day. This vision was justified by the Iraq War of 2003 when again the British army was the only one capable of any integrated effort with the main US forces, although in the end its operation to take Basra and the oilfields was a discrete affair. To a very large degree, then, the British army of the early twenty-first century has been, and continues to be, shaped by its ever closer association with that of Uncle Sam.

But that close association – special military relationship, indeed – has not always encompassed the whole spectrum of conflict. After the débâcle of Vietnam and the unhappy experience of intervention in Somalia in 1992, the US army returned (mentally at least) to what it

saw as its primary – indeed, some argued, its exclusive – function: defence of the Republic. In other words, ‘warfighting’. The Pentagon saw ‘operations other than war’ not only as problematic and inconclusive (whereas the use of military force was meant to be

decisive)

but also as positively harmful to the warrior ethos. When the Balkans erupted in civil war with the collapse of the Republic of Yugoslavia in 1992, the US army was unwilling and probably doctrinally unable to join the hastily formed UN protection force (UNPROFOR) in Bosnia, for the Security Council mandate was for a peacekeeping operation only, not peace enforcement. Both the US and Britain took the view that enforcement would be tantamount to warfighting if either of the factions chose to resist – a relatively clear-cut operation therefore. But an intervention to deliver humanitarian aid while fighting continued between the factions, and with no mandate for the use of force beyond self-protection, was an altogether trickier business. The term ‘peacekeeping’ seemed wholly inappropriate, since there was quite evidently no peace to keep. The ‘international community’ decided it could not sit idly by, however; and so, despite the ambiguity, danger and double-dealing entailed, it chose to do the minimum: send peacekeepers anyway, and hope they would be able to do

something.

As peacekeepers in Bosnia, the UNPROFOR contingents wore blue berets (or blue helmets when the situation required) and all vehicles were painted white, for peacekeepers were meant to derive their security from being recognized as UN troops. The white paint served, too, to concentrate the minds of politicians who from time to time demanded that the peacekeepers take on one or other of the warring factions when some atrocity aroused public opinion; for as the best-known of UNPROFOR’s commanders General Sir Michael Rose (who had commanded the SAS in the Falklands) put it, to do so would be to make war, and ‘you can’t make war in white-painted vehicles’.

Into this apparently hopeless situation a British battalion, the Cheshire Regiment, stepped bravely at the outset of the mandate and began making operational doctrine on the hoof. By combining techniques learned over long years in Northern Ireland with battle skills honed in BAOR – whence they had come (in their Warriors) – they were able to do far more than had been thought possible. Other battalions which in turn relieved them stretched the boundaries of what became known as ‘wider peacekeeping’ even further and gave a lead to other nations who were gingerly putting on the same blue

berets. Nevertheless ‘peacekeeping’ was a dangerous business: over 300 UN troops were killed in Bosnia – a higher casualty rate than in the Gulf War. And from time to time experience at the ‘sharp end’ was no different from the fighting in any number of ‘small wars’ east of Suez, or indeed in the South Atlantic. In March 1994 the Duke of Wellington’s Regiment was one of the first units to enter the besieged Bosnian Muslim enclave of Gorade, nominally a UN ‘safe haven’ but under strong pressure from the Bosnian Serbs, who were trying to over-run it and hotly contesting the entry of UN troops. One of the Dukes’ patrols fired 2,000 rounds of ammunition in a fifteen-minute battle with a Serb patrol in which a Dukes soldier and seven Bosnian Serbs were killed. And then the following month a young corporal, Wayne Mills, won the Conspicuous Gallantry Cross, second only to the VC. His patrol, coming under heavy fire from a Bosnian Serb patrol, returned fire, killing two, and then withdrew – as their orders required – but the Serbs followed up, still firing. As the Dukes patrol reached the edge of a clearing Mills, with limited ammunition and knowing that his orders were to fire only in self-defence, ordered his men to withdraw while he remained behind to cover them across the open ground. Not until he had killed half the patrol and its leader did the Serbs break off the attack – with Mills himself down to his last few rounds.