The Making Of The British Army (25 page)

Read The Making Of The British Army Online

Authors: Allan Mallinson

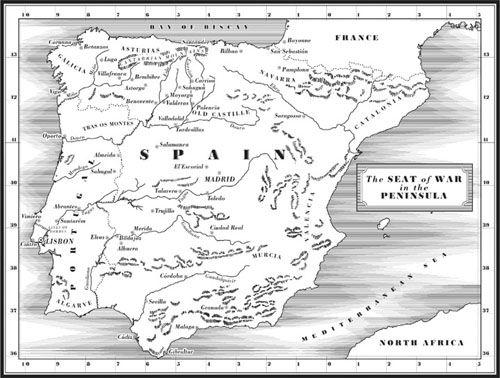

The Iberian Peninsula: first steps, 1808

WITH THE VICTORIES IN EGYPT IT WAS AS IF THE ARMY HAD SUDDENLY FOUND

a military version of the philosopher’s stone: everything it now touched seemed to turn to gold. Even in India, where French money and advisers were sent to gnaw at the growing British commercial and territorial strength, there were impressive victories against dramatic odds. In 1799 the young Colonel Arthur Wellesley, still in his twenties and commanding a division, had drawn one of the most troublesome thorns in the East India Company’s side – Tippoo, Sultan of Mysore. Wellesley’s march on Tippoo’s capital, Seringapatam, and its siege and storming, were as superbly organized as the 1793 campaign in Flanders – in which he ‘learned what

not

to do’ – had been disorganized.

56

Wellesley’s eldest brother, Richard, was governor-general in Calcutta, principal of the governors who ruled the East India Company’s ‘presidencies’ of Madras, Bombay and Bengal. After Seringapatam he appointed Local Major-General Wellesley governor of conquered Mysore. It was a spectacular act of nepotism, but an inspired one nevertheless, enabling the future duke of Wellington to add diplomatic and administrative skills to those of the soldier – skills that would be

of incalculable value when in Portugal and Spain he found himself grappling with the demands of a major expedition reliant on allies.

In 1803 Wellesley also gained the experience of planning and conducting an entire campaign, and in arid country against a vastly more numerous and elusive enemy, the Mahrattas. It was as fine a grounding for the Peninsular War as he could have wished, not least for its setbacks and reverses which gave him a healthy appreciation of ‘time and space’, one of the most intangible factors in warfare. And at the culminating battle of Assaye he learned just how close-run a battle could be and yet be saved by the commander’s determination and cool head. In later life he would claim that of all his battles he was proudest of Assaye – perhaps not surprisingly, for he had very nearly lost it, and by his own miscalculation and uncharacteristic impetuosity. India taught the duke his trade as a commander at the tactical level, at which battles are fought, and also at the operational level, at which campaigns are planned and carried out. And thanks to his brother’s patronage he learned what war meant at the strategic level too, where the political ends are translated into a scheme of action, both military and non-military In these ways India laid the foundations for the success of the British army in Europe in the early nineteenth century, as it would again for the new generations in 1914–18 and 1939–45.

By 1801 the fight had been knocked out of Britain’s continental allies, and when war broke out again within a year of the delusory Peace of Amiens the whole power of France and its conquered territories was turned on Britain. The army at once mustered in Kent and along the Thames estuary to repel the expected invasion, while the Royal Navy began the remarkable campaign that was to culminate in Nelson’s destruction of the Franco-Spanish fleet at Trafalgar two years later in October 1805, wiping out Bonaparte’s hopes of landing on English soil. The concentration of troops in the south-east had unintended beneficial consequences. For the first time, senior officers now had a chance to organize systematic training at brigade level and above. It was a blessing for many regimental commanders too, for since barracks were still a rarity their men were dispersed all about the countryside in billets and could rarely be mustered for training in more than company strength. Major-General John Moore, lately returned from Egypt, was given command of the key coastal defences from Dover to Dungeness. At the prompting of the duke of York, he began a training scheme for

light infantry at Shorncliffe camp near Folkestone, the beginning of the sustained effort to gain agility on the battlefield as well as devastating volley fire.

It was at this time, too, that the rifle made its first appearance in the hands of regular British troops. In 1800, again on the initiative of the duke of York, an ‘Experimental Corps of Riflemen’ made up of detachments from several regiments had been mustered for training in Windsor Forest under Colonel Coote Manningham, who had thought out his ideas while serving in the West Indies. Once proficient with the new Baker rifle

57

and its associated

jaeger

tactics, these experimental riflemen were supposed to return to their units as sharpshooters. However, a chance raid on Ferrol in north-west Spain gave the Experimental Corps its chance to put theory into practice, and it so spectacularly proved the rifleman’s worth that afterwards the corps was reconstituted as a regiment of the line – the 95th (Rifle) Regiment of Foot – and a second battalion was raised. They were renamed the Rifle Brigade in 1816.

The 95th Rifles, popularized by Bernard Cornwell’s ‘Sharpe’ novels, were not quite the first troops to carry the rifle and wear green. In December 1797 the 5th Battalion of the 60th Royal Americans had been raised in England by Baron Francis de Rottenburg, who armed them with rifles and dressed them in green jackets with discreet red facings. Moore used Rottenburg’s treatise on riflemen and light infantry, and Manningham’s regulations, to train his brigade at Shorncliffe. Its original three components, the 95th Rifles and the 43rd (Monmouthshire) and 52nd (Oxfordshire) Light Infantry, would evolve through various forms of name and county affiliations to their amalgamation in 1966 as the Royal Green Jackets (whose reputation for marksmanship, innovation and fast marching was matched only by that for the mass production of generals). Their motto was that given by Wolfe to the 60th Royal Americans at Quebec:

celer et audax –

‘swift and bold’. Historians have sometimes observed that the French light infantry –

voltigeurs

and

tirailleurs –

were a sort of military manifestation of Rousseau’s concept of the natural man, in contrast to the close ranks of stiff-necked

mousquetaires

of the

ancien régime.

What

animated their British counterparts is difficult to say, but the rifle regiments quickly became, if not exactly fashionable, then a

corps d’élite

and a key part of the military machine. When eventually Lieutenant-General Sir Arthur Wellesley took supreme command in the Peninsula he issued orders that the 60th and the 95th were always to form the vanguard when the army moved.

But all these innovations did not yet amount to a system as such, and the military successes – outside India – were small-scale affairs. There was no permanent organization of brigades, let alone divisions; and therefore no staff. What would today be called combat support (artillery and engineers) continued to function independently, much as in Marlborough’s day – a separate ‘army’ of the Board of Ordnance – giving rise to the same problems. Likewise, what is now called combat service support (transport and supply) remained an extension of the Treasury. And although the uncooperativeness of these departments has sometimes been exaggerated, it was still too often the case that while the commander of the fighting troops looked towards the enemy, the commanders of the artillery, engineers and commissariat looked back towards London. Commissariat officials were rewarded for their frugality, whereas a field commander wanted all the supplies he could get. The old quartermaster’s joke that if he had been meant to give away kit then his offices would have been called ‘issues’ and not ‘stores’ was writ large in the commissariat.

For all the duke of York’s reforms, therefore, and for all the innovations and small-scale successes, the army was in no fit state yet to mount a major, sustained campaign on the Continent. British musketry may have been better than French in the firefight, but Bonaparte’s army was simply too good an instrument of war to meddle with. Once wrong-footed by its superior powers of manœuvre and logistics, no army seemed able to resist the heavy firepower it could bring to bear, or the advance of its columns of infantry – as the Austrians, the Russians and then the Prussians learned in 1805 and 1806 at Ulm, Austerlitz and Jena. Like the cobra, the army of Bonaparte could be avoided, and it could be put off by great agility. But let it strike and it was deadly.

Britain had to come to grips with the Grande Armée somewhere, however, and soon. Indeed, the second great period in the making of the British army would be one almost of an army in search of a battlefield. And as with the first a century before, although there would be

several men with a right to share in the laurels, one man would stand way above the rest – so far above the rest, in fact, that, just as with Marlborough before Blenheim, had he fallen before the definitive battle there would have been no one to fill his boots. So towering a figure did the duke of Wellington become that his exasperated ‘By God, I don’t think it would have served had I not been there!’ after Waterloo might have applied equally at any time in the preceding seven years.

And he might easily

not

have been there. Arthur Wellesley’s exploits in India had come to the attention of Whitehall – not surprisingly, for his brother wrote the dispatches – and the Tory administration was doubly approving of a capable general who was also ‘one of us’ (he was soon to be an MP and privy counsellor). Wellesley would be especially favoured by the support of his fellow Anglo-Irishman Robert Stewart, Lord Castlereagh, secretary for war between 1805 and 1809, and foreign secretary from 1812. Elder brother Richard, now Marquess Wellesley and back from India, was able with Castlereagh to provide a certain seamlessness at the strategic level, a sort of ‘top cover’ without which younger brother Arthur would have found the politics even harder going during the later years of the Peninsular War. But now, at the beginning of 1808, Lieutenant-General Sir Arthur Wellesley (he was made Knight of the Bath in 1804 and promoted after the expedition to capture the Danish fleet at Copenhagen in 1807) was not only the youngest lieutenant-general in the army, he was the most junior. While he had every right to expect some independent command, he understood full well that Sir John Moore and others senior to him would have command of any really great undertaking.

That great undertaking was now, at last, at hand. For although Bonaparte had dealt with the major continental powers, Britannia ruled the waves, and as well as blockading French naval ports the Royal Navy continued to range freely among French colonial possessions, intercepting her trading ships and those of French conquests and neutrals alike. In turn, the only way Bonaparte could conceive of defeating Britain was by destroying her commerce, for without treasure from exports she could neither pay for the navy nor offer subsidies to continental allies. He therefore declared a Europe-wide embargo on trade with Britain, the so-called ‘continental system’. It was soon failing on two counts, however. First, the New World increasingly took up the trade which the continental ports refused; and second, in desperately trying to close off every point of trade Bonaparte over-reached himself

by invading Portugal through Spain, and then replacing the Spanish Bourbon king with his own brother, Joseph Bonaparte.

El Tres de Mayo

, Goya’s masterpiece, was according to the art critic Sir Kenneth Clark ‘the first great picture which can be called revolutionary in every sense of the word, in style, in subject, and in intention’. In it a French firing squad executes Spanish captives in the early hours of the morning: the day before, 2 May 1808, in Madrid and throughout Castile the Spanish had risen up against the French. For the Spaniards’ former ally – alongside whose ships they had fought against Nelson at Trafalgar – was now an occupying power.