The Last Spike: The Great Railway, 1881-1885 (67 page)

Read The Last Spike: The Great Railway, 1881-1885 Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

The trains sped off, usually two at a time, at staggered intervals, puffing through Carleton Place, Pembroke, North Bay, and Sudbury towards Dog Lake, where the real ordeal would begin. The officers, at Van Horne’s insistence, were given first-class accommodation even though the government’s requisition did not cover sleeping cars and Van Horne doubted if he could collect for it. But he was looking further ahead than the bills for the mass movement of some three thousand troops. For the sake of the railway’s long-term image it was “important that the report of the officers as to the treatment of the troops on our line should be most favourable.” For that reason the

CPR

was prepared to carry free any clothes or goods sent out to the soldiers by friends or relatives. As for the men themselves, Van Horne ensured that there would, whenever possible, be mountains of food and gallons of hot, strong coffee. Better than anybody else, he knew what the troops were about to face. He could not protect them from the chill rides in open flat cars and sleighs, or from the numbing treks across the glare ice, but he could make sure that his army marched on a full stomach.

5

The cruel journey

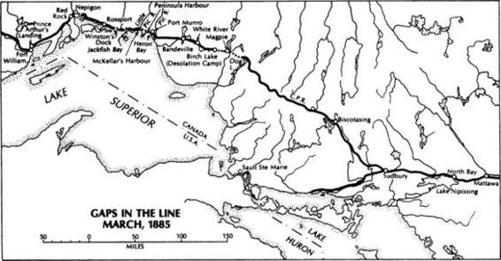

As the trains rolled westward and the cheering faded, the men from the cities, farms, and fishing villages of the East began to glimpse the rough face of the new Canada and comprehend for the first time the real dimensions of the nation. Out of North Bay the land stretched off to the grey horizon, barren and desolate, the slender spruce rising in a ragged patchwork from the lifeless rock. The railway was completed for passenger traffic only to Biscotasing. Here the troops encountered the first of the

CPR

construction towns, a hard-drinking, backwoods village of some hundred huts and log cabins interspersed with mercantile tents, all decked out for the occasion with Union Jacks and bunting. Between the canvas pool halls and shops (some bearing crude signs reading “Selling Off at Cost”) were the inevitable blind pigs. On April 1, the day the Queen’s Own arrived at Biscotasing, the police had just destroyed five hundred gallons of illicit whiskey.

The first gap in the line began near Dog Lake, another construction camp not far from the site of modern-day White River, reputedly the coldest spot in Canada. Here the railway had prepared a Lucullan feast of beef, salmon, lobster, mackerel, potatoes, tomatoes, peas, beans, corn, peaches, currants, raisins, cranberries, fresh bread, cakes, pies, and all the tea and coffee needed to wash it down. It was the last night of comfort the soldiers would know for several days and the start of an adventure that all would remember for the rest of their lives.

The men, packed tightly in groups of eight in sleighs provided by the construction company, set off behind teams of horses down the uncompleted right of way. At every unbridged ravine and unfilled cut the sleighs were forced off the graded surface, sometimes for several miles, and onto the tote road, a roller coaster path that cut through forests, ran over stumps, windfalls, and rocks, dipped up and down through gorges and wound through seemingly impassable stretches of tightly packed trees. In

some places the sleighs encountered boulders seven or eight feet high; in others they pitched into holes as deep as graves – the occupants flung over the dashboards and into the steaming haunches of the terrified horses. “No description,” wrote one man, “could give an idea of the terrible roads through the woods.” Spills and accidents were so frequent they were taken as normal. One sleigh carrying members of the 65th overturned no fewer than thirteen times in the forty miles between Dog Lake and the end of track at Birch Lake. Men already half frozen in the twenty-degree below weather were hurled out and submerged in six feet of powdery snow, often with all their equipment. Caps, mitts, mufflers, side arms, and other articles of luggage were lost in the white blanket through which the sleighs reared and tumbled. One member of the London Fuseliers was completely buried under an avalanche of baggage; a comrade was almost smothered when a horse toppled onto him. When sleighs carrying troops westward encountered empty sleighs returning eastward for a second load, chaos resulted: the detours were only wide enough to permit a single team to pass through without grazing the trees on either side. If a horse got a foot or two out of the track, the runners would lock onto a tree trunk, or, worse still, rise up on a stump, tilting occupants and baggage into the snow.

Generally, this trip was made by night when the sun was down and the weather cold enough to prevent the snow from turning to slush. The men crouched in the bottoms of the sleighs, wrapped in their greatcoats and covered with robes and blankets; but nothing could keep out the cold. To prevent themselves from freezing, officers and men would leap from the

careering sleighs and trot alongside in an attempt to restore circulation. For some units, the cold was so intense that any man who left any part exposed even for a few minutes suffered frostbite. “What they passed through that night all hope will never require to be repeated,” a reporter travelling with the Grenadiers wrote back.

The teams were changed at Magpie camp, a half-way point along the unironed right of way. Here was more food – pork, molasses, bread, and tea, the staples of the construction workers. Many arriving at Magpie thought they had reached the end of their ordeal and were discomfited when the bugle blew and they realized that it was only half over. Scenes of confusion took place in the darkness – the men scrambling about seeking the sleighs to which they had been assigned, the snow dropping so thickly that friends could not recognize each other in the dark, the horses whinnying and rearing, the half-breed teamsters swearing, the officers and non-coms barking orders, the troops groaning with the realization that everything they owned was soaking wet and that they would have to endure four more hours of that bone-chilling journey.

Out of the yard the horses galloped, starting along a route utterly unknown to them, depending solely on their guides and their own instincts, tumbling sometimes sleighs and all over the high embankment, righting themselves, and plunging on. The entire gap between Dog Lake and Birch Lake took some nine hours to negotiate, and at the end stood a lonely huddle of shacks, which was swiftly and accurately named “Desolation Camp.”

It deserved its title. A fire had swept through the scrub timber, leaving the trees naked of bark and bleached a spectral white. A cutting wind, rattling through the skeletal branches, added to the general feeling of despair. The only real shelter was a tattered tent, not large enough to accommodate the scores who sought refuge in it. Yet some men had to remain there for hours, their drenched clothing freezing to their skins in temperatures that dropped as low as thirty-five below.

The 10th Royal Grenadiers arrived at Desolation Camp at five one morning after a sleigh journey that had begun at eight the previous evening. There were no trains available to take them farther, and so they endured a wait of seventeen hours. They did not even have the warmth of a fire to greet them. Tumbling out of the sleighs like ghosts – for the falling snow had covered them completely – they tried to huddle in the tent through whose several apertures bitter drafts blew in every direction. “There was probably more heroism in facing cheerfully the scene of disillusionment that confronted the men that morning than during the heat

of battle,” one observer commented. The tent was so crowded that it was not possible to lie down. Some men lit fires outside in three feet of snow, only to see the embers disappear into deep holes melted through the crust. Others rolled themselves in their blankets like mummies and tried to sleep, the snow forming over them as it fell.

Every regiment that passed through Desolation Camp had its own story of hardship and endurance. Some members of the Queen’s Own were rendered hysterical by the cold; when the trains finally arrived they had to be led on board, uncomprehending and uncaring. One sentry saw a form flitting from tree to tree in the ghostly forest and, believing the enemy was upon them, called out the guards; it was only a blanket caught in the wan moonlight, fluttering in the wind. Although most troops had had very little sleep since leaving civilization, they were denied it at Desolation Camp because sleep could mean certain death when the thermometer dropped. The Halifax Battalion, the last to arrive, had to endure a freezing rain, which soaked their garments and turned their greatcoats into boards. When men in this condition dropped in their tracks, the guards were ordered to rouse them by any means, pull them to their feet, and bring them over to the fires to dry. There they stood, shivering and half conscious, until the flat cars arrived.

In these cars, sleep again was all but impossible, especially for those who travelled at night in below-zero weather with a sharp wind blowing. The cars were the same gravel cars used by construction crews to fill in the cuts. Rough boards had been placed along the sides to a height of about six feet, held in place by upright stakes in sockets. There was no roof, and the wind and snow blew in through the crevices between the planks. Rough benches ran lengthwise and here the men sat, each with his two issue blankets, packed tightly together, or huddled lengthwise on the floor. The officers were provided with a caboose heated by a stove, but many preferred to move in with the men.

For the Governor-General’s Body Guard, such a journey was complicated by the need to minister to the animals. There were no platforms or gangways in the wild; the men were obliged to gather railway ties and construct flimsy inclined planes up which the horses could be led to the cars. Because the snow was generally three or four feet deep and the ties sheathed in ice, the makeshift ramps had to be covered with blankets so that the animals would not lose their footing. All had to be watered and fed before the men could rest. Nor could they be moved by sleigh across the Dog Lake gap to Desolation Camp at Birch Lake; the cavalrymen rode or led their animals the entire distance. When the cavalry moved

by train, the horses were placed in exactly the same kind of flat cars as the men. Unloading them at each point occupied hours. It was necessary to remove all the hind shoes to prevent injuries to men and steeds; even with that precaution, one fine black stallion was so badly injured by a kick from another horse that he had to be destroyed.

The artillery had its own problems. It was not easy to load the nine-pounders onto the flat cars. At one construction camp, four husky tracklayers from Glengarry were assigned to do the job. One of them ran a crowbar into the muzzle of an artillery piece to get purchase, a desecration that caused the major in charge to fly into a rage. He dismissed the navvies, called for twenty of his own men to tie a rope around the breech and, with great difficulty, succeeded in having it hauled up an inclined platform and onto the car.

The track that led from Desolation Camp to the next gap at Port Munro was of the most perfunctory construction. The ties had been laid directly onto the snow and in some sections, where a thaw had set in, four or five ties in succession, spiked to the rails, would be held clear off the ground for several inches. One man likened the train’s movement to that of a birchbark canoe, “only, of course, on a larger scale.” Trains were thrown off this section of track daily and the rails were slowly being bent by the heavy passage. It was rarely possible to exceed five miles an hour. “It was,” a member of the Queen’s Own Rifles wrote home, “about the longest night any of us ever put in.”

The Grenadiers, who made the trip relatively swiftly, put in five hours on the open cars before they reached Bandeville, the half-way point on the completed portion of track. The men, being packed close together, had the advantage of mutual body warmth, but the officers, who had more room in the caboose, were in pitiful condition. “At one end of the car, lying on a stretcher on the floor was a poor fellow suffering from rheumatism and quite helpless with surgeon Ryerson patiently sitting at his head where he had been trying all night, with little success, to snatch a little sleep. The gallant colonel … with elbows on knees, was sitting over the stove looking thoughtfully into the embers with eyes that have not known a wink of sleep for 50 hours. Then there was Major Dawson whose system appeared to be rebelling against the regularity of life to which it had been so long accustomed … Capt. Harston, with a face as red as a boiled lobster sitting with arms folded on his knees [was] the very picture of incarnate discomfort.…”

At Bandeville (which consisted of a single shack in the wilderness) the men were fed sandwiches and hot tea. Some were so stiff with cold they had to be lifted out of the cars, “but warmth and food soon revive them

and their troubles are no sooner over than they are forgotten.” Others were so bone weary that when they reached the warmth of the eating house, the change in temperature was too much for them, and they dropped off into a sleep so deep it was almost impossible to awaken them to eat. One man fell into the snow on the way into the shanty. When his comrades picked him up, he seemed to be insensible. They carried him inside and found there was really nothing wrong with him; he had simply gone to sleep on his feet.