The Last Spike: The Great Railway, 1881-1885 (70 page)

Read The Last Spike: The Great Railway, 1881-1885 Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

George Stephen wanted out; Ottawa had become painful to him. He could no longer bear the varnished atmosphere of the East Block, whose outer offices he had been haunting since December. Those two political nerve centres, the Russell House and the Rideau Club, had become agonizing symbols of setback and defeat. He was determined to shake the slush of the capital from his boots, never to return.

On March 26, the day of the bloody engagement at Duck Lake, dispirited and sick at heart, he went to his room in the Russell House and packed his bags. He had already dispatched a letter to the Prime Minister explaining that, as a result of a conversation that morning, he was satisfied the government could not give the railway the aid it required. There was in that letter none of the desperation that characterized so much of his correspondence with Macdonald. Stephen was drained of emotion; all that remained was a kind of chilly aloofness, a sense of resignation: “I need not repeat how sorry I am that this should be the result of all our efforts to give Canada a railway to the Pacific ocean. But I am supported by the conviction that I have done all that could be done to obtain it.” That was it. The great adventure was over. Stephen prepared to return to Montreal to personal ruin and public disgrace.

It was hard to conceal anything in the Russell House, for it was the real political headquarters of the capital. It had been growing with the city, adding wing after wing, tearing down old portions, adding on new – a turret or two here, an ornamental tower there, a small forest of iron columns, new floors of polished marble. By 1885, it occupied almost the entire block at Sparks Street and Elgin. Contractors, diplomats, working politicians, and

VIPS

flocked to its lobby. It was not possible that Stephen’s departure could go unremarked.

Among the crowd in the lobby that evening were a

CPR

official, George H. Campbell, and two cabinet ministers – Mackenzie Bowell, Minister of Customs (who had originally opposed the railway loan), and Senator Frank Smith, Minister without Portfolio. Campbell was one of several

CPR

men working on members of the Government to try to change their minds regarding further aid to the railway. Bowell had already been converted; Smith, who had met several times with Van Horne, did not need to be. He was the head of a firm of wholesale grocers in Toronto which was a supplier to the

CPR

and, in addition, he was personally involved in railways as well as in allied forms of transportation. Of all of Macdonald’s

inner circle, with the exception of Charles Tupper and John Henry Pope, he was the most enthusiastic supporter of the railway.

As the three men chatted together, Stephen appeared in the lobby and walked towards the office to pay his bill. He was clearly downcast and exhausted with mental strain and anxiety. Smith was alarmed at his appearance and his obvious intentions.

He hurried towards Stephen, engaged him in conversation, and called the others over. Campbell, who later recounted the incident to Katherine Hughes, Van Horne’s original biographer,

*

recalled the gist of Stephen’s words: “No, I am leaving at once; there is no use – I have just come from Earnscliffe and Sir John has given a final refusal – nothing more can be done. What will happen tomorrow I do not know – the proposition is hopeless.”

Smith, whose powers of persuasion were considerable, managed to dissuade Stephen from leaving. (One story has it that he kept him talking so long that the

CPR

president missed his train and had no choice but to stay over.) Smith promised that he and Mackenzie Bowell would make a final effort that evening to change the Prime Minister’s mind. They drove to Earnscliffe for a midnight interview, leaving Campbell with orders to remain with Stephen and not to allow any other person access to him.

Though Smith held no cabinet portfolio – his business interests occupied too much of his time – he was one of the most powerful politicians at Ottawa, a handsome, large-hearted Irishman with a vast following among the Roman Catholics of Ontario. He was popular with almost everybody, friend or foe. Indeed, he had once subscribed to the campaign fund of a political opponent (who was, admittedly, a co-religionist running against an Orangeman).

Joseph Pope

†

said of him that he was possessed of a “keen business sagacity and sound common sense.” He had worked himself up from immigrant farm hand and grocery-store clerk to the ownership of one of the largest wholesale houses in Canada. From this base he branched out into transportation. The pleasure boats that ran to Niagara were his and so was the Toronto horsecar system, which became a model for American cities. (Smith introduced the coffee-pot method of collecting fares at the door to save the conductor from having to move down the car.) He had reached a kind of pinnacle in both finance and transportation; he was president of a bank (the Toronto Savings and later the Dominion) and of

a railway (the Northern). His political career was equally spectacular. Mayor of London at forty-four, he was a senator at forty-nine and by that time a close friend and confidant of the Prime Minister, who believed that Smith could personally deliver the Catholic vote in Ontario, or withhold it.

There is an amusing story told of Smith in the 1878 campaign which illustrates, in the most literal manner, his political clout. A very bad speaker in the Albert Hall on Yonge Street, opposite Eaton’s, in Toronto, was clearly losing votes for the party when Smith rose from a back seat, walked up to the chairman, and whispered in his ear. Smith then walked over beside the speaker and gave him a nudge with his powerful elbow. The speaker stopped, looked at Smith, and began to speak again. Smith, who was a tall and muscular man, gave him a heavier nudge. The speaker doggedly kept on. A succession of nudges from Smith finally edged the unfortunate orator right off the platform and out of sight. As the next speaker took the floor and Smith strode back to his seat, the crowd gave him such a round of applause that he was persuaded to stand and take a bow.

He was an engaging figure – a liberal supporter of the opera,— a patron of the theatre, the president of the Ontario Jockey Club, the owner of a stable of spirited horses, and a free spender. A word from him could mean a change in the party’s fortunes. If any man could swing the Prime Minister and the Cabinet, it was Smith.

He and Bowell arrived at Earnscliffe and attempted for more than an hour to persuade the Prime Minister to reconsider the matter of the loan. It was the second time within a year that a midnight attempt had been made to reprieve the

CPR

. Smith, apparently, was less successful than Pope had been in 1884. Macdonald may have been shaken, but he would not move. Nevertheless, when Smith returned at 2 a.m. he was able to convince Stephen that he should not yet give up the ghost. Guarded by the vigilant Campbell, whose instructions were to keep him incommunicado, the

CPR

president agreed to revise his proposal for relief while Smith worked on Macdonald and the Cabinet. It was said that for Campbell the three days that followed were the most anxious of his life. He was the constant companion of “a man torn with anguish and remorse whose heart seemed to be breaking with compassion for friends whose downfall he felt himself responsible for.”

Stephen had his revised proposition ready for the Privy Council the following day. That it was not rejected out of hand must be seen as a victory for Frank Smith. It was no wonder that years later Van Horne

wrote to Smith that everybody connected with the railway felt a debt of gratitude to him “which they can never hope to repay.” McLelan might resign if the loan went through, but Smith made it clear that he would resign if it did not; and Smith controlled more votes.

Over the next fortnight, as the troops from eastern Canada were shuttled off to the plains, a series of protracted and inconclusive negotiations took place regarding the exact terms of the proposed loan, which must pass both Council and Parliament. With every passing day, Stephen grew more nervous and distraught. The government had him in a corner. Macdonald wanted to be repaid in hard cash, not land; the government would retain a lien on the land, together with the proposed mortgage bonds as security. Moreover, it would insist that the

CPR

take over the North Shore line between Montreal and Quebec City. Under pressure from Ottawa, the Grand Trunk could be persuaded to give up the line to the Quebec government which, in turn, would lease it back to the

CPR

at an annual cost of $778,000. It was doubtful, Stephen thought, if it could earn one hundred thousand dollars annually, it was so run down. (Later that year the

CPR

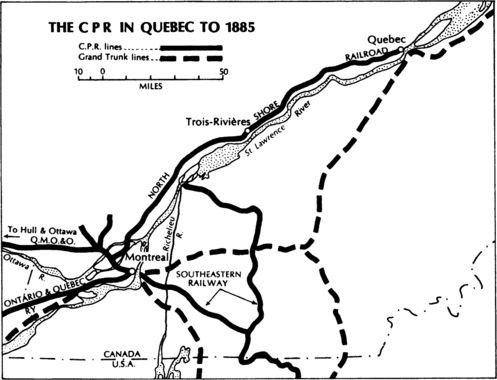

bought the line outright.)

But there was no help for it. Reports were coming in of a serious strike at Beavermouth in the shadow of the Selkirks; an angry mob of navvies, demanding their pay, was marching on the

CPR’S

construction head

quarters. Stephen saw Tilley immediately, gave him the news of the trouble, and warned the finance minister of the “utter impossibility of averting an immediate & disastrous collapse” unless some way could be found to give the company temporary aid to tide it over while the matter was being discussed at painful length in the Cabinet and in Parliament. Tilley was not helpful; he was one who believed the government would have to take over the railway.

Once again the

CPR

president was at the end of his tether. Once again he told Macdonald: “… it is impossible for me to carry on this struggle for life, in which I have now been for over 4 months constantly engaged, any longer.” The delay had finished him, he said – rendered him “utterly unfit for further work.” He was sick at heart, fed up with politicians, betrayed by the very man in whom he had placed his confidence. Yet he could not quite bring himself to leave. He waited four more days. Silence. Finally, on April 15, Stephen gave up. That evening he took the train back to Montreal, to the great mansion on Drummond Street in which he must have felt a trespasser since it was, in effect, no longer his. And there the following morning the dimensions of the disaster the railway faced were summed up for him in a curt wire from Van Horne:

“Have no means paying wages, pay car can’t be sent out, and unless we get immediate relief we must stop. Please inform Premier and Finance Minister. Do not be surprised, or blame me if an immediate and most serious catastrophe happens.”

3

Riot at Beavermouth

Of all the mercurial construction camps along the

CPR’S

mountain line, the one at the mouth of the Beaver River was the most volatile. It was dominated by saloons – forty of them – all selling illegal whiskey (usually a mixture of rye, red ink, and tobacco juice) at fifty cents a glass, and each taking in as much as three hundred dollars a night. “Rome has hitherto taken the palm for howling,” the Calgary

Herald

reported somewhat ambiguously in 1885; “this is because not many people have heard of Beaver Creek.”

The gamblers and whiskey peddlers had originally concentrated at Donald, on the east side of the Columbia. In order to remove his navvies from temptation, James Ross caused the track to be taken across the river. There, along the Beaver flats, where the pale green waters meandered out of the mountains through a carpet of ferns and berries, he established a

company store and a postal car. The plan did not work. The coarser elements soon moved across the Columbia bridge and began to build saloons, dance halls, and brothels out of cedar logs. Under British Columbia law the saloons were legal as long as they were licensed by provincial authorities. Under Dominion law it was illegal to sell liquor within the forty-mile railway belt. This caused a series of comic-opera disputes between representatives of the two jurisdictions all along the line in British Columbia.

Ross refused to allow

CPR

trains to provide the gamblers, saloonkeepers, and prostitutes with food or supplies. An upsurge of petty thievery and discontent followed. Sleighs left unguarded were robbed; subcontractors were tempted to sell provisions illegally at black-market prices. The town was awake most of the night to the sound of dancing, singing, and revelry. Sam Steele, the Mounted Police inspector in charge, remembered that “we were rarely to bed before two or three a.m., and were up in the morning between six and seven.…” Steele spent the forenoon disposing of prisoners – mainly drunks who had been lodged in jail overnight for their own safety – and the afternoon with summary trials for petty theft and assault.

By late March, the complaints over lack of pay began to gather into a discontented rumble that moved up and down the line in angry gusts. The men had been content to go without pay in the winter, but by early spring funds were needed for homesteads in Manitoba, Minnesota, and Dakota. Steele, who was the recipient of many of the complaints, counselled patience. He feared that a strike, if it came, would swiftly develop into a riot, sparked by a large number of “ruffians, gamblers and murderers from the Northern Pacific who had left it on the completion of that road.” He warned Ross of the danger of trouble; Ross remained unconvinced. Steele wired the Prime Minister that a strike was imminent but got no action; Macdonald had more serious troubles in Saskatchewan on his mind. At this critical point Steele was felled by a massive attack of fever, which he described as a Rocky Mountain typho-malarial fever (probably Rocky Mountain spotted fever, which had been identified only a few years before). Steele was forced to take to his bed, an unusual recourse, for he was known as an iron man, “erect as a pine tree and limber as a cat,” as his son described him. He was so ill he could scarcely lift his head from the pillow.