The Last Spike: The Great Railway, 1881-1885 (63 page)

Read The Last Spike: The Great Railway, 1881-1885 Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

In the face of continued government vacillation Major Crozier’s misgivings increased. He wired Dewdney in February urging that a surveyor be sent out at once to reassure the Métis, by his actions, that no one intended to trample on their customs in the matter of strip farms. He also wanted the question of land scrip handled immediately. Delay would be dangerous. “Delay causes uneasiness and discontent, which spreads not only among the Half Breeds but the Indians.”

But the Prime Minister’s mood that spring seemed to be delay, as George Stephen was finding to his own frustration. Macdonald appeared to exhibit a strange blindness towards the North West. He had shown it in 1869 at the time of the first Riel trouble. He had shown it repeatedly in the settlement of prairie communities, when, time and again, the rights of the settlers had been ignored. He had shown it with the Indians and now he was showing it with the Métis. There was a curious ambivalence about the Prime Minister’s attitude towards the new Canada west of Ottawa. At the time of Confederation he had ignored it totally, believing it unfit for anything but a few Indians and fur traders. Then, when the Americans seemed on the point of appropriating it by default, he had pushed the bold plan for a transcontinental railway. Suddenly once again he seemed to have lost interest. The railway was floundering in a financial swamp; the West was about to burst into flame. Macdonald vacillated.

Riel’s memory went back to those intoxicating moments in December, 1869, when, having seized Fort Garry without a shot, raised a Métis flag, and established a provisional government on the prairies, he had been able to deal with Canada on equal diplomatic terms and secure concessions for his people as the result of a bold

fait accompli

. Something along the same lines was in his mind in the early months of 1885. He would not need to resort to bloodshed; the threat of it would bring the Canadian government to its senses.

But times had changed since 1869. Technically, Riel had been on reasonably strong ground in the Red River valley; it was not actually part of Canada at the time. But the territory of Saskatchewan was a legal entity, and anyone forming a new government there was clearly a rebel, committing treason. More important, Riel ignored the presence of the railway. In 1869, the Red River had been an isolated community, separated from Canada by the rampart of the Shield. He and his Métis had existed almost in a vacuum and worked their will because the Canadian minority in the settlement could not be reinforced by soldiers from the East. Those conditions no longer held.

By March 13, Crozier was expecting a rebellion to break out at any moment. The

Saskatchewan Herald

reported that day that Riel had spoken in French to a large gathering outside the church, pointing to imminent hostilities between England and Russia and suggesting that it was a good time for the Métis to assert their rights.

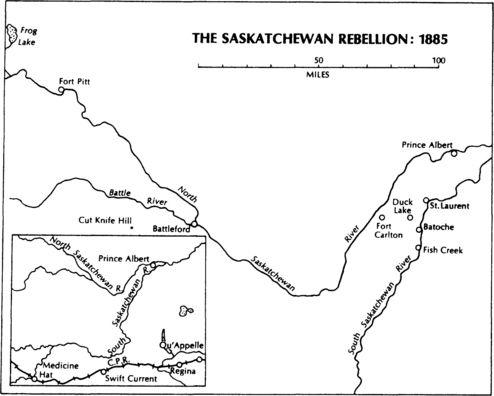

The

NWMP

commissioner, A. G. Irvine, dispatched a hundred reinforcements to Prince Albert. Rumour, winging across the prairies, raised that number to five hundred, so that Riel came to believe that the government had replied to his demands by raising an army against him. Events now began to accelerate. On March 18, the day before the festival of St. Joseph, the patron saint of the Métis, Riel took prisoners, seized arms in the St. Laurent-Batoche area, and cut the telegraph line between Batoche and Prince Albert. The following day, with his people assembled for the festival, he set up a provisional Métis government, as he had done in 1869. He did not want bloodshed, and when Gabriel Dumont urged

him to send messengers to enlist Indian support, Riel overruled him, believing Ottawa would now yield to the threat of insurrection.

He was, however, becoming more inflammatory. He told his people that five hundred policemen were on the way to slaughter them all. In the week that followed he and his followers, in Crozier’s words, “robbed, plundered, pillaged and terrorized the settlers and the country.” They sacked stores, seized and held prisoners, and stopped the mails. Riel and Crozier exchanged emissaries on March 21; the rebel leader’s clear intent was to convince the policeman that he was committed to a violent course of action. Dewdney wired Macdonald the following day that the situation looked very serious and that it was imperative that an able military man should be in the North West in case the militia had to be called out. On March 23, Macdonald dispatched Major-General Frederick Dobson Middleton to the Red River with orders that the militia should move. Macdonald who, incredibly, was “not aware of any causes for discontent,” belatedly dispatched his tardy commission to the spot to investigate the Métis land claims.

It was Riel’s intention to seize Fort Carlton and establish it as the capital of his new government. He demanded unconditional surrender from Crozier:

“We want blood! blood! If Carlton is not surrendered it will be a war of extermination; I must have an answer by 12 o’clock or we will attack and take the fort.”

Crozier decided to hold Fort Carlton with his policemen and a detachment of volunteers from Prince Albert. But he sent, on March 25, a sergeant and seventeen constables with eight sleighs to get provisions and ammunition from the trader’s store at nearby Duck Lake. It was a strange move, since it was inevitable that the Métis, under Dumont, who had already occupied and looted the store, would rebuff them. Three miles from Duck Lake, four of the Mounted Police scouts were turned back by a large number of pursuing Métis and Indians. The sleighs halted. Dumont and his followers drew up, behaving “in a very overbearing and excited manner.” The Prince of the Plains actually went so far as to prod the ribs of the

NWMP

interpreter with a cocked and loaded rifle while the Indians jeered at the police: “If you are men, now come in.” The party retreated.

This was too much for the impatient Crozier. The Force had been slighted. No one who wore the scarlet coat could countenance such a breach of the law. Without waiting for Irvine and his reinforcements, the superintendent set out with his fifty-five Mounted Policemen, forty-three Prince Albert volunteers, and a seven-pound cannon in tow.

Dumont, on horseback, watched them come. His Métis dismounted

and began to creep forward through a curtain of falling snow, partially encircling the police. Crozier drew his twenty sleighs up in line across the road and ordered his men to take cover behind them. A parley took place under a rebel white flag with Dumont’s brother Isidore and an Indian on one side and Crozier and a half-breed interpreter, John McKay, on the other. When Crozier extended his hand to the Indian, the unarmed native made a grab for McKay’s rifle. Crozier, seeing the struggle, gave the order to fire. Isidore Dumont toppled from his horse, dead. The rebels were already on the move, circling around the police left flank. Crozier put spurs to his horse and galloped back to the police lines through a hail of bullets. The Indian was already dead.

At this moment, with the Métis pouring a fierce fire on the police from two houses concealed on the right of the trail and outflanking them on the left, Louis Riel appeared on horseback through the swirling snow, at the head of one hundred and fifty armed Métis. He was grasping an enormous crucifix in his free hand and, when the police fired at him, he roared out in a voice that all could hear: “In the name of God the Father who created us, reply to that!”

Within thirty minutes Crozier had lost a quarter of his force killed and wounded. The Métis had suffered only five casualties. The North West Mounted Police were in retreat. The Saskatchewan Rebellion had begun.

3

“I wish I were well out of it”

Sunday, January 11, 1885, was the Prime Minister’s seventieth birthday, and on Monday all of Montreal celebrated this anniversary, which also marked his fortieth year in politics. It was almost fifteen years since he had promised British Columbia a railway to the Pacific, and in that period he had moved from the prime of life to old age. The rangy figure was flabbier; the homely face had lost some of its tautness; the hair was almost white; deep pouches had formed beneath those knowing eyes; the lines around the edges of the sapient lips had deepened; and on the great nose and full cheeks were the tiny purple veins of over-indulgence.

He was a Canadian institution. There were many at that birthday celebration in Montreal who were grandparents, yet could not remember a time when Macdonald had not been in politics. The reports of his imminent retirement through illness, fatigue, incompetence, scandal, or political manæuvre had appeared regularly in the press for all of the railway

days. His suicide had been rumoured, his death predicted, his obituary set in type ready for the presses to roll; but Macdonald had outlasted one generation of critics and spawned a second. He had left the country the previous fall with George Stephen, weary to the point of exhaustion, suffering once again from the stomach irritation that seemed to be the bane of Canadian political leaders. Now he was back, miraculously revived, jaunty as ever, making jokes about his health and telling his friends and supporters that as long as his stomach held out the Opposition would stay out.

He would need a healthy stomach for the days that lay immediately ahead; but as he drove through two miles of flaming torches on that “dark soft night,” under a sky spangled by exploding rockets, to a banquet in his honour, he was in the mellowest of moods. In his speech he could not help adding to the eulogies that he heard on all sides about the great national project, which was nearing completion. “In the whole annals of railway construction there has been nothing to equal it,” he said. Only a few of those in attendance – George Stephen was one – could appreciate the irony of that statement. The Prime Minister might just as easily have been referring to the immensity of the financial crisis that the railway faced.

Just the previous Friday, Stephen had dispatched one of his frantic wires to the Prime Minister: “Imminent danger of sudden crisis unless we can find means to meet pressing demands. Smaller class creditors getting alarmed about their money. Hope Council will deal today with question of advancing on supplies.” That week, rumours of the company’s financial straits began to leak out. On January 16, one of the Montreal papers reported that the

CPR

could not meet its April dividend, that attacks on the London market had caused another drop in the price of its stock, and that the company was paying for its normal cash purchases with notes at four months. The rumours were true. Within a fortnight the stock was down below 38; not long after it hit a new low of 333a.

Sir John Rose in London dispatched a worried note to Macdonald: “I fear you will have to apply some drastic remedy to these Grand Trunk people. You have no idea to what an extent the Papers teem with attacks on Canadian credit – one of the last is that the Dominion will wriggle out of its guarantee on the

C.P

. stock!!… If the dividend is passed it will have a very disastrous effect on the

permanent

credit of the Cy.”

Stephen had worked out with Tupper and Macdonald a scheme whereby the unissued stock of the

CPR

would be cancelled by government legislation, the lien on the railway removed, and a more or less equivalent

amount of cash raised by mortgage bonds applied to the entire main line of the railway, with principal and interest on them guaranteed by the government. About half the cash from these bonds would be used to help pay off the loan of 1884. The rest would go to the company as a loan to pay for expenditures not included in the original contract. The remainder of the 1884 loan would be paid off in land grant bonds.

Financially, it was an ingenious scheme. Politically it was disastrous. The previous year, Blake had taunted the Government about the

CPR

loan: “Don’t call it a loan. You know we shall never see a penny of this money again.” This was strong meat; Macdonald could foresee the hazards of allowing the Opposition to cry: “We told you so!” The farming counties of Ontario, where so much of his strength rested, were not enamoured of the railway: the value of farmland in the East had been reduced because so many people had departed for the North West, lured by tales of the new country opened up by the rails.

Macdonald, at 70, was a different man from the 55-year-old who, in 1870, had firmly believed that no time should be lost in building a railway to the Pacific. Then, if anything, he had been overly rash in his promises to British Columbia; now, the ageing chieftain seemed weary and confused, hesitant of taking any political risk, inept in his handling of the Indian Affairs Department and, before that, of the Department of the Interior (whose portfolio he held until 1883), insensitive to the problems of the North West and, apparently, sick to death of the railway he had helped to create. The picture of the Prime Minister in 1885 is that of a leader who has lost his way, stumbling from one crisis to another, propped up by bolder spirits within his cabinet and by the entreaties of men like Stephen and Van Horne. His policy of delay, which from time to time had worked in his favour, was disastrous in 1885; it brought bloodshed to the North West and came within an hour of wrecking the

CPR

.