The Language Instinct: How the Mind Creates Language (18 page)

Read The Language Instinct: How the Mind Creates Language Online

Authors: Steven Pinker

Within a phrase, then, the verb is a little despot, dictating which of the slots made available by the super-rules are to be filled. These demands are stored in the verb’s entry in the mental dictionary, more or less as follows:

dine:

verb

means “to eat a meal in a refined setting”

eater = subject

devour:

verb

means “to eat something ravenously”

eater = subject

thing eaten = object

put:

verb

means “to cause something to go to some place”

putter = subject

thing put = object

place = prepositional object

allege:

verb

means “to declare without proof”

declarer = subject

declaration = complement sentence

Each of these entries lists a definition (in mentalese) of some kind of event, followed by the players that have roles in the event. The entry indicates how each role-player may be plugged into the sentence—as a subject, an object, a prepositional object, an embedded sentence, and so on. For a sentence to feel grammatical, the verb’s demands must be satisfied.

Melvin devoured

is bad because

devour

’s desire for a “thing eaten” role is left unfulfilled.

Melvin dined the pizza

is bad because

dine

didn’t order

pizza

or any other object.

Because verbs have the power to dictate how a sentence conveys who did what to whom, one cannot sort out the roles in a sentence without looking up the verb. That is why your grammar teacher got it wrong when she told you that the subject of the sentence is the “doer of the action.” The subject of the sentence is often the doer, but only when the verb says so; the verb can also assign it other roles:

The big bad wolf

frightened

the three little pigs. [The subject is doing the frightening.]The three little pigs

feared

the big bad wolf. [The subject is being frightened.]

My true love

gave

me a partridge in a pear tree. [The subject is doing the giving.]

I

received

a partridge in a pear tree from my true love. [The subject is being given to.]

Dr. Nussbaum

performed

plastic surgery. [The subject is operating on someone.]

Cheryl

underwent

plastic surgery. [The subject is being operated on.]

In fact, many verbs have two distinct entries, each casting a different set of roles. This can give rise to a common kind of ambiguity, as in the old joke: “Call me a taxi.” “OK, you’re a taxi.” In one of the Harlem Globetrotters’ routines, the referee tells Meadowlark Lemon to shoot the ball. Lemon points his finger at the ball and shouts, “Bang!” The comedian Dick Gregory tells of walking up to a lunch counter in Mississippi during the days of racial segregation. The waitress said to him, “We don’t serve colored people.” “That’s fine,” he replied, “I don’t eat colored people. I’d like a piece of chicken.”

So how do we actually distinguish

Man bites dog

from

Dog bites man?

The dictionary entry for

bite

says “The biter is the subject; the bitten thing is the object.” But how do we

find

subjects and objects in the tree? Grammar puts little tags on the noun phrases that can be matched up with the roles laid out in a verb’s dictionary entry. These tags are called

cases

. In many languages, cases appear as prefixes or suffixes on the nouns. For example, in Latin, the nouns for man and dog,

homo

and

canis

, change their endings depending on who is biting whom:

Canis hominem mordet. [not news]

Homo canem mordet. [news]

Julius Caesar knew who bit whom because the noun corresponding to the bitee appeared with -

em

at the end. Indeed, this allowed Caesar to find the biter and bitee even when the order of the two was flipped, which Latin allows:

Hominem canis mordet

means the same thing as

Canis hominem mordet

, and

Canem homo mordet

means the same thing as

Homo canem mordet

. Thanks to case markers, verbs’ dictionary entries can be relieved of the duty of keeping track of where their role-players actually appear in the sentence. A verb need only indicate that, say, the doer is a subject; whether the subject is in first or third or fourth position in the sentence is up to the rest of the grammar, and the interpretation is the same. Indeed, in what are called “scrambling” languages, case markers are exploited even further: the article, adjective, and noun inside a phrase are each tagged with a particular case marker, and the speaker can scramble the words of the phrase all over the sentence (say, put the adjective at the end for emphasis), knowing that the listener can mentally join them back up. This process, called agreement or concord, is a second engineering solution (aside from phrase structure itself) to the problem of encoding a tangle of interconnected thoughts into strings of words that appear one after the other.

Centuries ago, English, like Latin, had suffixes that marked case overtly. But the suffixes have all eroded, and overt case survives only in the personal pronouns—

I, he, she, we, they

are used for the subject role;

my, his, her, our, their

are used for the possessor role;

me, him, her, us, them

are used for all other roles. (The

who/whom

distinction could be added to this list, but it is on the way out; in the United States,

whom

is used consistently only by careful writers and pretentious speakers.) Interestingly, since we all know to say

He saw us

but never

Him saw we

, the syntax of case must still be alive and well in English. Though nouns appear physically unchanged no matter what role they play, they are tagged with silent cases. Alice realized this after spotting a mouse swimming nearby in her pool of tears:

“Would it be of any use, now,” thought Alice, “to speak to this mouse? Everything is so out-of-the-way down here, that I should think very likely it can talk: at any rate, there’s no harm in trying.” So she began. “O Mouse, do you know the way out of this pool? I am very tired of swimming about here, O Mouse!” (Alice thought this must be the right way of speaking to a mouse: she had never done such a thing before, but she remembered having seen, in her brother’s Latin Grammar, “A Mouse—of a mouse—to a mouse—a mouse—O mouse!”)

English speakers tag a noun phrase with a case by seeing what the noun is adjacent to, generally a verb or preposition (but for Alice’s mouse, the archaic “vocative” case marker

O

). They use these case tags to match up each noun phrase with its verb-decreed role.

The requirement that noun phrases must get case tags explains why certain sentences are impossible even though the super-rules admit them. For example, a direct object role-player has to come right after the verb, before any other role-player: one says

Tell Mary that John is coming

, not

Tell that John is coming Mary

. The reason is that the NP

Mary

cannot just float around tagless but must be casemarked, by sitting adjacent to the verb. Curiously, while verbs and prepositions can mark case on their adjacent NP’s, nouns and adjectives cannot:

governor California

and

afraid the wolf

, though interpretable, are ungrammatical. English demands that the meaningless preposition

of

precede the noun, as in

governor of California

and

afraid of the wolf

, for no reason other than to give it a case tag. The sentences we utter are kept under tight rein by verbs and prepositions—phrases cannot just show up anywhere they feel like in the VP but must have a job description and be wearing an identity badge at all times. Thus we cannot say things like

Last night I slept bad dreams a hangover snoring no pajamas sheets were wrinkled

, even though a listener could guess what that would mean. This marks a major difference between human languages and, for example, pidgins and the signing of chimpanzees, where any word can pretty much go anywhere.

Now, what about the most important phrase of all, the sentence? If a noun phrase is a phrase built around a noun, and a verb phrase is a phrase built around a verb, what is a sentence built around?

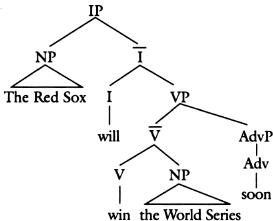

The critic Mary McCarthy once said of her rival Lillian Hellman, “Every word she writes is a lie, including ‘and’ and ‘the.’” The insult relies on the fact that a sentence is the smallest thing that can be either true or false; a single word cannot be either (so McCarthy is alleging that Hellman’s lying extends deeper than one would have thought possible). A sentence, then, must express some kind of meaning that does not clearly reside in its nouns and verbs but that embraces the entire combination and turns it into a proposition that can be true or false. Take, for example, the optimistic sentence

The Red Sox will win the World Series

. The word

will

does not apply to the Red Sox alone, nor to the World Series alone, nor to winning alone; it applies to an entire concept, the-Red-Sox-winning-the-World-Series. That concept is timeless and therefore truthless. It can refer equally well to some past glory, a hypothetical future one, even to the mere logical possibility, bereft of any hope that it will ever happen. But the word

will

pins the concept down to temporal coordinates, namely the stretch of time subsequent to the moment the sentence is uttered. If I declare “The Red Sox will win the World Series,” I can be right or wrong (probably wrong, alas).

The word

will

is an example of an auxiliary, a word that expresses layers of meaning having to do with the truth of a proposition as the speaker conceives it. These layers also include negation (as in

won’t

and

doesn’t

), necessity (

must

), and possibility (

might

and

can

). Auxiliaries typically occur at the periphery of sentence trees, mirroring the fact that they assert something about the rest of the sentence taken as a whole. The auxiliary is the head of the sentence in exactly the same way that a noun is the head of the noun phrase. Since the auxiliary is also called

INFL

(for “inflection”), we can call the sentence an IP (an

INFL

phrase or auxiliary phrase). Its subject position is reserved for the subject of the entire sentence, reflecting the fact that a sentence is an assertion that some predicate (the VP) is true of its subject. Here, more or less, is what a sentence looks like in the current version of Chomsky’s theory:

An auxiliary is an example of a “function word,” a different kind of word from nouns, verbs, and adjectives, the “content” words. Function words include articles (

the, a, some

), pronouns (

he, she

), the possessive marker’

s

, meaningless prepositions like

of

, words that introduce complements like

that

and

to

, and conjunctions like

and

and

or

. Function words are bits of crystallized grammar; they delineate larger phrases into which NP’s and VP’s and AP’s fit, thereby providing a scaffolding for the sentence. Accordingly, the mind treats function words differently from content words. People add new content words to the language all the time (like the noun

fax

, and the verb

to snarf

, meaning to retrieve a computer file), but the function words form a closed club that resists new members. That is why all the attempts to introduce gender-neutral pronouns like

hesh

and

than

have failed. Recall, too, that patients with damage to the language areas of the brain have more trouble with function words like

or

and

be

than with content words like

oar

and

bee

. When words are expensive, as in telegrams and headlines, writers tend to leave the function words out, hoping that the reader can reconstruct them from the order of the content words. But because function words are the most reliable clues to the phrase structure of the sentence, telegraphic language is always a gamble. A reporter once sent Cary Grant the telegram, “How old Cary Grant?” He replied, “Old Cary Grant fine.” Here are some headlines from a collection called

Squad Helps Dog Bite Victim

, put together by the staff of the

Columbia Journalism Review: